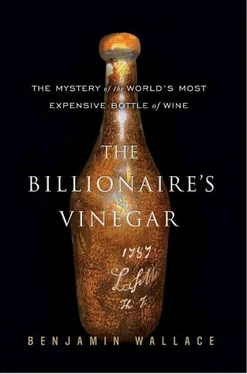

Sokolin first heard of the Jefferson bottles when he read an account of the Forbes purchase in Wine Spectator . Later, when he visited the Forbes Galleries to view the 1787 Lafite, he was shocked that it was displayed under a spotlight and warned the security guard. Then, when the cork slipped, Sokolin says, Kip Forbes called him and asked what to do. Sokolin told him there were two options: either throw out the wine, or let Sokolin jump on a plane and take it to Lafite for recorking. The Forbeses decided to keep the bottle as it was.

Sokolin learned that he might be able to get his own Jefferson bottle when Littler, with whom he’d done business in the past and who knew of his Jeffersonian proclivities, called and said, “Bill, I think I’ve got your bottle.” Littler said he could arrange for Sokolin to take the bottle on consignment. The two men began to explore their options for complimentary transport. Air France offered to fly Littler and the bottle to America by Concorde, but that would require Littler to get to London. British Airways flew straight from Manchester, and volunteered two first-class tickets—one for Littler, one for the bottle. After making sure Sokolin had obtained insurance, on Friday, October 22, 1988, Littler set out for the Manchester airport.

British Airways issued a press release about the flight and photographed Littler and the bottle checking in and taking their seats on the plane, where a clutch of publicists and flight attendants dressed up the Margaux, peeking out of the same tennis bag in which Littler had received it, with blanket, headphones, and seat belt. Landing at JFK in New York at 6:00 p.m., Littler went through customs, gave the bottle to Sokolin, turned on his heel, and boarded a return flight to England. There, a hand-scrawled fax from his friends at Farr Vintners awaited him. It accompanied one of the pictures of Littler and the bottle that had appeared in a newspaper, and said, “Don’t Die of Ignorance: Always wear gloves when you’ve got your fingers in a punt.” In the photo, Littler’s thumb was in the “punt,” the concavity in the base of a wine bottle.

The following day, Sokolin’s interested party had a heart attack while playing golf and died, Sokolin told Littler. Therefore he no longer had a customer. Littler said he was going to be in New York a month later and would collect the bottle at that time. But then Sokolin said he had another client who was interested, and Littler’s trip was pushed back a few months. The bottle stayed with Sokolin.

Sokolin displayed it in his shop and encouraged wine journalists to write about it. He also sent a fax to Malcolm Forbes with the latest D. Sokolin price list, touting the arrival of the 1787 Jefferson Margaux:

Dear Malcolm,

This is an event of some magnitude. And it ain’t the price—250,000 for this bottle.

Th. Jefferson’s spirit is in this bottle.

He and G Washington had a COMPANY—called the WINE COMPANY—chartered in 1774.

THE PURPOSE—to get the DEMON RUM out of the Colonies—The equivalent of drugs today.

And replace it with WINE… WINE

It’s a good story and better than the ones the candidates have chosen.

This little bottle will start drugs out as requested by the SPIRIT OF JEFFERSON…

Sounds nuts—?

I think the bottle would make nice duo at FORBES—and the story is the point…

All the best, Bill Sokolin

The story was the point, but Forbes wasn’t interested. Heeding the salesman’s adage that if at first something doesn’t sell, you should ask for more, Sokolin kept hiking the price, first to $394,000. Then, after seeing a rickety footstool sell at auction for $290,000, which Sokolin thought absurd, he repriced the bottle at an entirely arbitrary $519,750.

IT WAS DURING this lull that Sokolin attended the Four Seasons event. The sponsors were Chateau & Estate and Château Margaux. By the late 1980s, an annual U.S. roadshow was de rigueur for the top growths of Bordeaux. While, on a mass scale, America had come late to wine, its high-end collectors had exercised a disproportionate influence on the market since the late 1960s. As of 1990, a quarter of all Pétrus and half of the production of the Domaine de la Romanée-Conti, the most esteemed producer in Burgundy, would be going to the U.S. In the spring of 1989, the Margaux team were in New York to promote the 1986 vintage, considered one of their strongest showings since the Mentzelopoulos family had bought the estate more than a decade earlier.

Corinne Mentzelopoulos began the evening by getting up and talking about the special vintages, 1953 and 1961, that Margaux was providing that night, and about the 1986 wine that would be tasted. Then the meal got under way. A few courses had already been served when Sokolin realized he should have brought the bottle with him. What better occasion to show off this extraordinarily rare bottle of Margaux than at a dinner to honor its makers? He said so to his wife Gloria.

“Don’t be ridiculous,” she said.

“Nope,” he said. “I’m going to get it.”

Sokolin took a taxi to the prewar building where he lived on the Upper West Side, across a darkened lawn from the Museum of Natural History. Entering his ninth-floor apartment, Sokolin passed an oversized retro poster ad for Mumm’s Champagne and foyer bookcases packed with works about wine and Jefferson. He crossed the blond parquet floor and turned into the dining room, where, instead of wallpaper, the ends of wooden cases that had once contained great wines were arranged in a vinous mosaic. A shelf displayed two reproductions of Jefferson’s wineglasses, a gigantic Lafite bottle opened after Gloria’s mother’s funeral, and an eighteenth-century Madeira decanter Sokolin had opened for the party to launch his book Liquid Assets . He retrieved the Jefferson bottle from a freestanding refrigerated wine closet in the corner of the room.

When he arrived back at the Four Seasons, half an hour after he had left, he brought the bottle directly to the Margaux table and said to Madame Mentzelopoulos, “I bet you never saw a bottle this old.” She had, of course, seen this very bottle, during its recorking for Whitwhams. Sokolin left it with the table for thirty minutes. “He was showing it to everyone,” Julian Niccolini, then the maître d’, recalled later. “Everyone was suspicious of this bottle.” Before dessert, Sokolin retrieved it from the Margaux table and took it to show to Rusty Staub.

Sokolin was cradling the bottle in a bag, with his left arm, when it happened. Niccolini saw the whole thing. Just inside the Pool Room, to the left of the door, stood a gueridon, a low, metal-topped trolley used as a service station by waiters. When Sokolin was a few steps into the room, headed toward Staub, he brushed past the gueridon. Wine immediately began to spill onto the carpet.

Minutes later, Sokolin was running from the room, trailing splotches of what looked like blood on the pale stone underfoot. He strode down a long, white marble corridor that led to the Grill Room, past the hostess station, and down the stairs to the lobby, which was scattered with black Barcelona chairs. When Sokolin put the bag and bottle down on a counter as he retrieved his coat, more of the wine leaked out, and three people dipped their fingers in it. One, licking his finger, said the wine was “cooked.” Niccolini thought it tasted like mud.

NOW IN HIS overcoat, Sokolin pushed out through the double doors onto an especially charmless block of midtown Manhattan and flagged down a taxi. Back in the Pool Room, in the spot where he had last been standing, a crowd gathered. In the chaos of his departure, Sokolin had left the two loose bottle shards at the restaurant. Howard Goldberg, from the New York Times, took one piece as a souvenir, and Paul Kovi, the co-owner of the restaurant, took the second. Meanwhile, Gloria Sokolin, unaware of what had happened, was wondering where her husband was. Then she saw Goldberg.

Читать дальше