This sense of exploration is crucial to Berger’s conception of writing. His essays are journeys, fuelled by a self-replenishing supply of ideas. For Salman Rushdie, in a review reprinted in Imaginary Homelands , these ideas are the most distinctive and important feature of Berger’s output. Entirely reasonable, an observation like this needs to be seen in the context of the widespread idea that writers do not need ideas, are even hindered by them. At the end of an essay in which Auden is berated for being ‘easily infatuated’ by ideas, for constantly ‘indulging his weakness for notions’, Craig Raine comes straight out and — echoing a favourite bleat of John Carey’s — declares: ‘We need ideas, but not in our art.’ This belief — and it is hard not to think of Oxford as its heartland — is a serious blot on the English literary landscape. It means we have tended to rely on exotic foreign imports (Borges, Calvino, Kundera and, most recently, W. G. Sebald) to do the idea stuff for us, thereby — the parallel with football is irresistible — impoverishing the development of the domestic game. The corollary of this is that someone like Bruce Chatwin who had a few (half-baked) ideas is radically overvalued, almost as a compensatory reflex. Berger, meanwhile, has come to be regarded as a kind of honorary European. (Nothing wrong with that, of course, but, to repeat something I said fifteen years ago in the preface to Ways of Telling , it is not enough simply to lobby for Berger’s name to be printed more prominently on an existing map of literary reputations; his example urges us fundamentally to alter its shape.)

In her teens Rebecca West was drawn to Ibsen who ‘corrected the chief flaw in English literature, which is a failure to recognise the dynamism of ideas’. With characteristic vehemence West later decided that Ibsen ‘cried out for ideas for the same reason that men cry out for water, because he had not got any’, but the general point still stands. ‘That ideas are the symbols of real relationships among real forces that make people late for breakfast, that take away their breakfast, that make them beat each other across the breakfast-table, is something which the English do not like to realise.’ That the author of ‘The Eaters and the Eaten’ realises this is evident on every page of this book.

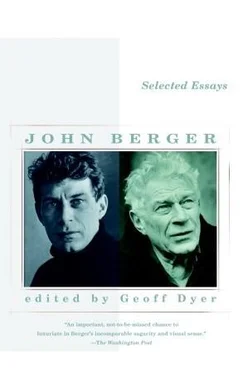

The purpose of which is, quite simply, to make available a comprehensive selection of essays from Permanent Red (in America, Toward Reality), The Moment of Cubism, The Look of Things, About Looking, The White Bird (in America, The Sense of Sight ) and Keeping a Rendezvous. A couple of previously uncollected items are also included. Hopefully a balance has been struck between the continuity — emphasised by the inclusion of different essays on the same artists — and variegation noted earlier. Many of Berger’s books exist between genres and this volume perhaps hovers between two stools in that it is too slim to merit the subtitle ‘Collected Essays’, but more substantial than ‘Selected’ tends to suggest. Hopefully it will serve both as a one-volume edition of his essays and as a kind of Berger Reader. It is one answer — mine, not John’s — to that question, ‘Which book of Berger’s should I read first?’

Geoff Dyer, March 2001

From Permanent Red ; (US title Toward Reality )

Preface to the 1979 Edition

This book was first published in 1960. Most of it was written between 1954 and 1959. It seems to me that I have changed a lot since then. As I re-read the book today I have the impression that I was trapped at that time: trapped in having to express all that I felt or thought in art-critical terms. Perhaps an unconscious sense of being trapped helps to explain the puritanism of some of my judgments. In some respects I would be more tolerant today: but on the central issue I would be even more intransigent. I now believe that there is an absolute incompatibility between art and private property, or between art and state property — unless the state is a plebeian democracy. Property must be destroyed before imagination can develop any further. Thus today I would find the function of regular current art criticism — a function which, whatever the critic’s opinions, serves to uphold the art market — impossible to accept. And thus today I am more tolerant of those artists who are reduced to being largely destructive.

Yet it is not only I who have changed. The future perspective of the world has changed fundamentally. In the early 1950s when I began writing art criticism there were two poles, and only two, to which any political thought and action inevitably led. The polarization was between Moscow and Washington. Many people struggled to escape this polarization but, objectively speaking, it was impossible, because it was not a consequence of opinions but of a crucial world-struggle. Only when the USSR achieved (or was recognized to have achieved) parity in nuclear arms with the USA could this struggle cease to be the primary political factor. The achieving of this parity just preceded the Twentieth Congress of the CPSU and the Polish and Hungarian uprisings, to be followed later by the first obvious divergences between the USSR and China and by the victory of the Cuban Revolution. Revolutionary examples and possibilities have since multiplied. The raison d’ětre of polarized dogmatism has collapsed.

I have always been outspokenly critical of the Stalinist cultural policy of the USSR, but during the 1950s my criticism was more restrained than now. Why? Ever since I was a student, I have been aware of the injustice, hypocrisy, cruelty, wastefulness and alienation of our bourgeois society as reflected and expressed in the field of art. And my aim has been to help, in however small a way, to destroy this society. It exists to frustrate the best man. I know this profoundly and am immune to the apologetics of liberals. Liberalism is always for the alternative ruling class: never for the exploited class. But one cannot aim to destroy without taking account of the state of existing forces. In the early 1950s the USSR represented, despite all its deformations, a great part of the force of the socialist challenge to capitalism. It no longer does.

A third change, although trivial, is perhaps worth mentioning. It concerns my conditions of work. Most of this book was first written as articles for the New Statesman. They were written, as I have explained, at the height of the Cold War during a period of rigid conformism. I was in my 20s (at a time when to be young was inevitably to be patronized). Consequently every week after I had written my article I had to fight for it line by line, adjective by adjective, against constant editorial cavilling. During the last years of the 1950s I had the support and friendship of Kingsley Martin, but my own attitude towards writing for the paper and being published by it had already been formed by then. It was an attitude of belligerent wariness. Nor were the pressures only from within the paper. The vested interests of the art world exerted their own through the editors. When I reviewed an exhibition of Henry Moore arguing that it revealed a falling-off from his earlier achievements, the British Council actually telephoned the artist to apologize for such a regrettable thing having occurred in London. The art scene has now changed. And on the occasions when I now write about art I am fortunate enough to be able to write quite freely.

Re-reading this book I have the sense of myself being trapped and many of my statements being coded. And yet I have agreed to the book being re-issued as a paperback. Why? The world has changed. Conditions in London have changed. Some of the issues and artists I discuss no longer seem of urgent concern. I have changed. But precisely because of the pressures under which the book was written — professional, political, ideological, personal pressures — it seems to me that I needed at that time to formulate swift but sharp generalizations and to cultivate certain long-term insights in order to transcend the pressures and escape the confines of the genre. Today most of these generalizations and insights strike me as still valid. Furthermore they seem consistent with what I have thought and written since. The short essay on Picasso is in many ways an outline for my later book on Picasso. The recurring theme of the present book is the disastrous relation between art and property and this is the only theme connected with art on which I would still like to write a whole book.

Читать дальше