It is always a little disorienting, then, to leave these exhibitions of horror or even sorrow and enter the gift shop. Almost always there is a gift shop, selling the usual tourist trinkets that embody some supposed essence of the country, from lacquered paintings of young women in ao dai to dinner plates, chopsticks, opium pipes, and so on. One is also likely to encounter war memorabilia, American airplane and helicopter models sculpted from recycled Coke and beer cans, in the poor old days, or now, in the somewhat better days, made from brass. There are bullets and dog tags, advertised as the real things from the real war. These are small memories, produced on a lesser scale than what comes forth from the massive industrial production lines of nations and corporations. This is what we might think of when the term memory industry comes up — the cottage industry, the arts and crafts of the mnemonic world.

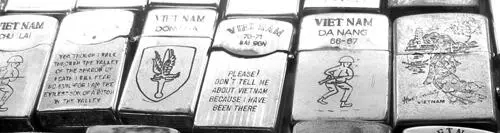

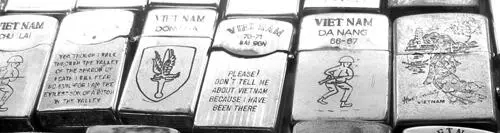

The best-known of these small memories are the ubiquitous Zippo lighters supposedly handled by a real American GI and imprinted with real GI slogans such as “Yea Though I Walk through the Valley of the Shadow of Death I Will Fear No Evil Because I Am the Evilest Son of a Bitch in the Valley.” 5The tourist who buys this kind of war remnant is presumably looking for a shred of the war’s aura. Whoever made these know that they are trading on a certain kind of authenticity when they take leftover Zippos, etch them with (in)famous GI slogans, and rough them up to give them the bruises of war and age. Cheap, mass produced, easily portable, the Zippo’s uses ranged from lighting cigarettes to torching huts to serving as the template for the American soldier’s imagination. These uses are not the only reason that the Zippo became one of the most popular symbols of the American occupation. The Zippo’s symbolic power comes from its mass-produced nature. While Ho Chi Minh is one of a kind, the Zippo is one of tens of thousands, its owner long forgotten. Its aura arises not just from the individuality of its purported owner but also from his being a member of the military’s rank and file, just like the consumer is a member of the tourist masses. Like the M-16, the Zippo is an industrial product with a memorable name, imbued with the antiheroism of slogans such as “When I Die, I Will Go to Heaven Because I Have Already Spent My Time in Hell.”

For the local craftsperson, however, the Zippo is just one more piece of American hardware to be recycled and sold to foreign tourists who deserve no better. Squeezing profits from tourists is another weapon of the weak in this asymmetric war, a sneaky tactic from a present scene that is a dark and comic repetition of the American war itself, when the grunt first faced off against the native. The native won that struggle by using the popular warfare of people’s struggle and, oftentimes, stealing the grunt’s own weapons. In the the war’s aftermath, the native faces off against the soldier’s descendant, the tourist, in an environment where a memory industry built on tourism replaces the war machine. 6My visit to the Plain of Jars in Laos was marked by the juncture between this memory industry and the war machine’s detritus. I flew into the small airport on a propeller-driven passenger plane carrying a multicultural contingent of U.S. Air Force medical volunteers on a humanitarian mission, clad in mufti rather than military gear. Male and female, they were mostly young, lean, pleasant, and fit, the older ones among them resembling suburban American fathers on vacation, pleasantly padded. Their forebears bombed this country, and the Plain of Jars in particular, with apocalyptic force. The enlisted man I mentioned this to did not want to talk about this history, while the clean-cut Air Force Academy graduate knew only some vague details. I wonder if they noticed the poster in the airport terminal, which advertised bracelets for peace, small things made from the metal of munitions. Is there anything more asymmetrical than air war waged against those without an air force, or a people forced to make a living by selling the fragments of bombs to those who bombed them?

A memory industry built on war might, in general, be called ironic, although greed or survival would be the more important elements. On Phonsavan’s single street, for example, there was a bar named Craters where the airmen gathered for a drink. The bar was not unique in turning the memory of massive carpet-bombing into the name for a site of rest and relaxation. This was small-scale memory work, pitching the past to those passing through, the way street vendors sold pirated copies of English-language classics about the war and these countries to tourists who wanted some education with their entertainment. At least the entrepreneurs in Saigon had been wittier and postmodern, naming their raucous, crowded, sweaty, and admittedly fun bars Apocalypse Now and Heart of Darkness, which the police occasionally raided to show that they were cracking down on what the government called the “social evils” of prostitution and drug use (I haunted these bars enough to witness each one being shut down by the police, who, clad in chartreuse green, win my award for the ugliest uniforms in the world). Turning horror into entertainment is a signature feature of the American industry of memory, as can be seen and heard in the “me so horny” line of dialogue from Stanley Kubrick’s jagged masterpiece Full Metal Jacket . This line inspired 2 Live Crew’s lewd, memorable rap smash “Me So Horny,” prosecuted for obscenity by Florida authorities, the irony of ironies, given how no one was prosecuted for obscenity for anything that happened during the war. Perhaps inspired by these examples, Southeast Asians have done their best to apply principles of capitalist exploitation to even the most dreadful past.

Some of the most memorable and remarked upon ways that these Southeast Asians mine the past are the tunnels and caves from where the war was fought or where civilians sought refuge from the bombing. As Mbembe says of the wars waged by necropolitical regimes, “the battlegrounds are not located solely at the surface of the earth. The underground as well as the airspace are transformed into conflict zones.” 7From the perspective of the emperors of the air, the subterranean is the retreat of the inhuman, where American soldiers called “tunnel rats” hunted for the human rats who lived in the tunnels, waiting to pop up from their spider holes to ambush American troops. But even the Americans grudgingly acknowledged that what they found were veritable cities, an underworld that was an uncanny reflection of the American camps above them, replete with kitchens, hospitals, bunkrooms, granaries, and the like. Perhaps these tunnels or others before them in the history of war influenced the philosophers Deleuze and Guattari when they came up with their notion of the “rhizome” to describe resistant social structures that were horizontal and root-like versus the arboreal, top-down, vertical structures of authority. War machines dislike tunnels, which literally undermine them, taking away their advantages and their pretense to humanity. The tunnel encounter, for the tunnel rat, inverts what Levinas asks for in seeing the other’s face. Instead of seeking conversation, an elaboration of shared humanity, the tunnel rat comes to kill, and comes face-to-face not only with the inhuman enemy but with his own inhumanity. Hence the terror of the tunnel for those who must go hunting in them, that they will be pried away from the armored protection of the war machines that provide an illusion of technological superiority, and through it, humanity.

Читать дальше