But the Vietnamese have a fighting chance on their own landscape, where they control the memorial apparatus of museums, monuments, schools, cinema, and media. Against foreigners, overseas Vietnamese, and its own people, the state’s industry of memory engages in asymmetric war. This is precisely why some visiting Americans feel shock when they encounter themselves as savages. They see themselves as the other, or they see themselves through the eyes of the other, a vertiginous experience. Still, the tourist, like the soldier, comes to this country at significant expense and time, versus the foreign movie-goer who, for the price of a few dollars, is exposed to American culture. Unless he chooses not to be, the Westerner is protected from the memories of others, while those others are periodically, oftentimes regularly, irradiated by Western memories whether they want to be or not.

As for scholars like me, collecting Vietnamese memories means repeated trips to Vietnam, to libraries, and to film festivals such as the one where I saw Living in Fear , the 2005 movie by the talented Bui Thac Chuyen. The plot is based on the true story of an unemployed South Vietnamese veteran in the postwar years who defuses landmines by hand, which echoes the story of Aki Ra in Cambodia. A former Khmer Rouge child soldier who turned himself into an unorthodox, self-taught one-man demining operation, Aki Ra founded the Land Mine Museum in Siem Reap. But whereas Aki Ra only had one wife, the hero of Living in Fear must support two, and after his close encounters with death, he is compelled to run home and make love to those wives. The movie combines sex and death with human feeling and drama, but beyond that, it exemplifies the industry of memory and its inequalities through the landmine as synecdoche for memory and industry. One country places landmines in another because it can, and the mined country lives with lethal memories embedded in its earth. Meanwhile, the industrial powerhouse that sows the bad seed can ignore the demand in movies such as Living in Fear that attention be paid.

Regardless of American neglect, the mined country must continue its own efforts at rebuilding a war-torn economy, from its industries to its leisure activities, which are sometimes the same, as is the case on the island of Con Son. I caught a plane for a short trip from Saigon to find quiet beaches, green mountains, and tranquil lakes. The landscape is too inviting to believe that the island will not become a tourist haven, where foreigners can snorkel, hike, get drunk, get laid, and pay an obligatory trip to one of the many moss-walled prisons, which, for now, can only be visited with a tour group. The French, who called the island Poulo Condor, originally built these prisons. After the South Vietnamese and their American advisors took over the prisons, they housed Viet Cong prisoners, both men and women. Most of the famous communist revolutionaries spent time here, and thousands of prisoners died within prison walls, including one of the most famous martyrs of all, Vo Thi Sau, the revolution’s Joan of Arc, who was executed as a teenager. One can visit her grave and comb one’s hair with plastic combs left on her tomb, an allusion to how she loved to brush her long, beautiful hair.

In these prisons, the heroism and sorrow that are fundamental to the revolutionary industry of memory are reconfigured in the preserved torture chambers and prison cells. Instead of golden statues of heroic revolutionary soldiers, one sees life-sized wax mannequins of nearly naked Vietnamese prisoners shackled or being beaten. These prisoners, also found in a more accessible place like the Hanoi Hilton, are crude, even cartoonish, which is fair, given that the torture they endured was crude and cartoonish. Americans remember the Hanoi Hilton as the prison where American pilots such as John McCain were kept and tortured, forgetting, or never knowing, that the French imprisoned Vietnamese revolutionaries first. But the Hanoi Hilton was small compared to the system of prisons on this island, which, before the jet age, was a remote island whose name must have struck fear into people’s hearts, the kind of place parents warned their disobedient children about. Con Son, the French predecessor to the American Guantanamo, was an island where terrible things happened, now reenacted through the dramatic poses and arrangements of mannequins. While the Hanoi Hilton depicts only the prisoners, here the American and South Vietnamese guards are also shown, standing aloof in guard posts, watching over prisoners at work, and pouring lime onto prisoners locked into tiger cages.

As I wander out into a prison yard, I see a scene of two men beating another, enacted on gravel. At a barred entrance to a cell, I see four men in fatigues kick and punch a half-naked, bleeding prisoner. I am watching scenes from a horror movie, captured and frozen in dioramas, as if cinema foreshadowed grisly memories of kidnapping, imprisonment, and torture. Of course these things happened first. Torture porn franchises such as Hostel and Saw and Texas Chainsaw Massacre are only stories, but a virulent, contaminated source has nurtured them. The terrors of the past that a war machine created has seeped into and infused the American unconscious. The trauma of war returns through the American industry of memory as horror movies that seem like ghosts themselves. They are bloodied and terrifying, often without history, except in cases such as George Romero’s 1968 zombie classic, Night of the Living Dead , where a white militia of good old boys wipes out the zombies in what they call a “search and destroy operation,” an unambiguous reference to the American strategy of the same name happening exactly at that time during the war. Romero understood necropolitics before Mbembe coined the term. He recognized that America needed zombies of the literal or figurative kind, the living dead whom one could kill or pacify without guilt. They are now everywhere: Hollywood has released an endless stream of zombie movies, and zombies are also the craze of television showrunners and highbrow novelists. These zombies were resurrected, unsurprisingly, in the age of the War on Terror, where they serve the same purpose they did in Night of the Living Dead , as allegories of the demonic other against whom Americans are fighting a war. But for the most part, outside of explicit allusions such as Romero’s, one has to go to this country, my birthplace, to see the torturous history of the living dead that many first glimpse in the movies, where the horrors of history have been transformed into entertainment.

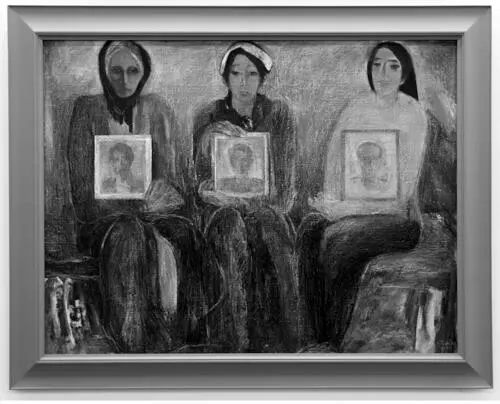

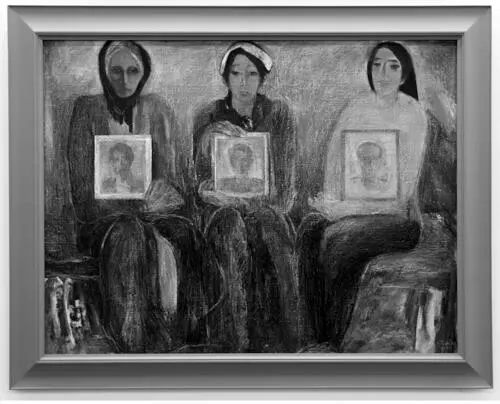

While it is easy to forget foreign wars, it is not so easy to forget wars fought on one’s own territory. Reminders are everywhere — those statues, those memorials, those museums, those weapons, those graveyards, those slogans. While one might not remember history, one cannot avoid its reminder. One must willfully turn one’s eyes away, or insulate them with filters that the state provides through ready-made stories of heroism and sacrifice. Their message is that the proper position toward the venerable past is to kneel on one knee of sorrow and another of respect. In Hanoi’s Fine Arts Museum, the acknowledgment of the dead is expressed through these emotional registers, as in Nguyen Phu Cuong’s sculpture Tuong Niem , or Commemoration , its hooded maternal figure cradling a bo doi ’s helmet, the mother herself absent, emptied by loss. Dang Duc Sinh’s 1984 oil painting, O moi xom, In Every Neighborhood , expresses similar sentiments by featuring three women wearing the sorrowful visages of widows or heroic mothers of the dead. While the Fine Arts Museum portrays death in a solemn and respectful fashion, elsewhere the victorious revolutionary regime cannot let go of the horror, or at least not yet. That is why the wax mannequins exist in the prison museums and in the diorama at the Son My Museum commemorating the My Lai massacre, or why photos of atrocities continue to be exhibited in numerous museums, most notoriously at the War Remnants Museum in Saigon. The state demands that its citizens remember the dead and how they died.

Читать дальше