Something an old cop would notice.

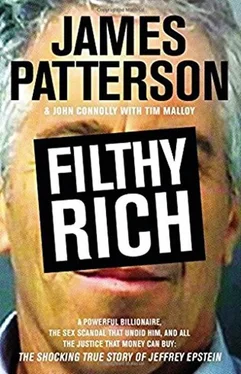

Reiter’s officers had told him about complaints they’d gotten a few months earlier-young women hanging around at the end of the block or coming and going at all hours from Epstein’s house. “There was some follow-up to that,” Reiter said in a deposition for B.B. vs. Epstein, a civil suit, brought by a victim, that Jeffrey eventually settled. “I think we may have encountered one or two of them. [We] may have done a little bit of surveillance or talked to neighbors as to whether or not they had seen that. I think we were of the general understanding that, yes, there were very attractive young women coming and going from Mr. Epstein’s residence.

“We did some level of further inquiry, and we were of the belief that they were all adults. And [we] were also of the belief that there was a possibility that there could be prostitution. But I mean that’s just not something that we heavily pursued-prostitution in private residences; it’s common everywhere in America. We didn’t believe that they were underage at that point, and so we had no further interest in it.”

Reiter had recalled those complaints on the day Epstein had shown up with his $90,000 donation. And when Reiter had walked Epstein downstairs, he couldn’t help but notice the tall, beautiful woman whom Epstein had brought with him to the station.

It struck him as strange that she was standing so stiffly, eyes cast downward, as though she were afraid to speak. Not a kid. But not a woman, either. Epstein did not introduce or even acknowledge her. To Reiter, this, too, seemed odd.

Indeed, the statuesque woman was Nadia Marcinkova, a nineteen-year-old beauty who lived at Epstein’s home and was described, by another girl, in a recorded interview with Detective Recarey, as one of Epstein’s “like, slaves.”

In September, several months into the investigation, Epstein calls Reiter directly and asks: Has Palm Beach bought the firearms simulator yet?

Cautiously, Reiter tells him that they’re still doing research.

If the department needs more funds, Epstein says, he’ll be happy to provide them.

Reiter thanks him graciously and hangs up. But he’s certain now that Epstein knows about the investigation. Thinking about Epstein’s crimes in Palm Beach makes him shudder. And, Reiter knows, if the charges are true, things are going to get ugly and public.

Cops like Reiter are family men, fathers. Some see so much that they’re no longer surprised by the ways of the world. Still, it helps to hold on to a natural capacity for outrage. Thefts are easy to understand: you see something you need, so you take it. Even murders make a kind of sense once you understand the motivation. There’s great satisfaction in catching a murderer. But what Epstein’s been up to is hard to explain.

Who is this guy?

Reiter’s detectives will have to get into Epstein’s head. To nail him, they’ll have to know him. And to do that, they’ll have to get to know the people around him. The police already know about Wendy. That’s one procurer, but out of how many?

What kind of person would bring children to a child molester?

And-Reiter can’t shake the idea-other victims had to be out there. That lined up with what Epstein’s neighbor reported: there were many girls. He needed to find them as quickly as possible. It was a race against time.

As long as Epstein was free in Palm Beach, more girls were sure to arrive at the side of the house on El Brillo Way.

Alison: September 11, 2005

It might start with the Palm Beach Daily News, which usually covers charity balls, equestrian events, and gallery openings. Reporters there would kill to sink their teeth into something so juicy. On top of that, Chief Reiter knows, Palm Beach is full of freelance paparazzi and seasoned semiretired journalists.

They’d kill for the story, too. For them, it’d be a real-life Body Heat .

Over at WPTV, the local NBC affiliate, the phone rings one day.

It’s a tip from a kid, sounding nervous. Something about girls from a local high school.

There’s a prostitution ring out in Palm Beach, says the boy.

The tip gets brought up in a midmorning meeting at which the producers divvy up ideas among the various reporters and newscasts.

“Where, exactly?” a producer asks.

“He didn’t say, exactly,” an intern replies. “He said that a very rich man was involved.”

“Who?”

“Didn’t say.”

“Did he leave a call-back number?”

“No. The kid sounded really young. Fourteen, fifteen years old.”

The producer thinks for a moment, makes a few scratches in his dog-eared notepad.

“Okay,” he says. “I’m not sure what we can do with that for the moment.”

At some point, some enterprising journalist will put enough pieces together to get a sense of the picture. Sooner or later, someone will talk. Maybe a parent. Maybe a cop’s girlfriend gets giddy at lunch. The girlfriend’s girlfriend mentions it to her husband, who says something to a golfing buddy in turn. Maybe the golfing buddy knows a reporter.

Or maybe some lawyer goes off the rez, blitzed off those martinis they serve at the Palm Beach Grill.

Sooner or later, there’s always talk. At that point, Chief Reiter’s job will get much, much harder-with Epstein on one side, the press on the other, and the chief taking flak from all sides. But right now, two months into Reiter’s investigation, the press is still speaking in whispers.

Right now, Reiter wants to keep it that way.

And, in the meantime, new pieces of the puzzle keep falling into place.

On September 11, a young woman named Alison gets pulled over by the police.* She’s carrying a small amount of marijuana. The patrol officer handcuffs her and puts her in the back of his vehicle. But Alison’s been in the back of a police car before, and she’s cocky and canny enough to pivot the conversation away from the dime bag she’s been busted with. She tells the officer a remarkable story about an older man engaging in sexual activities with high school girls. Alison knows about it firsthand, she says. She’s been going to the house on El Brillo Way since she was sixteen.

At first the cop’s skeptical. He hasn’t heard about the investigation into Jeffrey Epstein’s affairs. And, after all, Alison is a burnout. But back at the station, he finds out that Alison has not been bullshitting him.

The investigation is real.

Alison’s name and cell phone number match up with messages that have been pulled from Epstein’s trash. Instead of copping to a misdemeanor, she becomes another Jane Doe in the case that Chief Reiter’s colleague, Detective Joe Recarey, is building against Jeffrey Epstein.

The story Alison ends up telling is extremely disturbing.

Like Mary, she says, she was recruited in high school. She tells cops that Epstein would call her his “number one girl”-although, she suspects, there were many others.

Recarey takes her statement. In the excerpts that follow (transcribed from a tape recording made by the Palm Beach police), D stands for “Detective Recarey,” and V stands for “victim.”

D:Well, ah, start from, like, how you met him, and then I’ll-I’ll take you through.

V:Okay. Um, we [Alison and a female friend] worked at Hollister together in the Wellington Green mall, and I was mentioning to her how I wanted extra money to go to Maine…I wanted to go camping for the summer, and I couldn’t afford a plane ticket. And-she goes, “Oh, well, you can get a plane ticket in two hours.” I said, “What are you talking about?” Like, what are you-that didn’t make any sense to me, a plane ticket in two hours; what are you talking about? And she goes, “Oh, we can go give this guy a massage, and, um, he’ll pay two hundred dollars for, like, forty-five minutes or an hour.” And that’s all she told me-no details, no nothing.

Читать дальше