The next time Mary calls, Wendy picks up.

On the recordings made by Officer Pagan, Mary’s voice is tiny and tentative, while Wendy sounds mature, gruff, fully grown, like the femme fatale in some old black-and-white movie.

“Hey, what’s up?” she says impatiently.

“Nothing,” says Mary.

“I talked to Jeffrey, and I’m going to his house tomorrow morning,” says Wendy. “I’m going to set something up for you.”

“Cool. Like, what do you think?”

“I don’t know. I’m going to talk to him tomorrow morning when I go to his house about it.”

“Um, how much would I get paid?”

“Talk to him. I’ll talk to him tomorrow, and then I’ll bring you in the next day. You can talk to him about it.”

So far, so good, thinks Officer Pagan. But she needs more. She looks at Mary expectantly, but not too expectantly, she hopes. She can imagine how hard it must be for the girl. Or maybe she can’t imagine it at all. But either way, Mary seems to have gotten the message. Straightening up in her chair, she begins to press Wendy.

“I don’t know,” Wendy says in response. “I don’t know. You’re going to have to talk to him about it. I mean, I don’t really work for him like that. I just bring girls to him and they work for him…You can ask him, like, ‘What can I do to make more money?’”

Mary keeps pressing.

“The more you do, the more you get paid,” Wendy says finally.

“Want me to bring my sister for you? So that we can get paid more or something?”

“Well, yeah. That’s what I’m saying. I’m working tomorrow, and me and him are going to put a schedule together for you and your sister. So I’ll call you tomorrow when I leave Jeffrey with a schedule.”

“Okay, well, I don’t have a phone. So if you guys call me, I’d have to know what time so I could get the phone.”

“Okay. I’ll leave you a message. That’s fine. I’ll leave you a message.”

Noel St. Pierre: March 2005

Noel St. Pierre* thinks of the kids he grew up with in Haiti. His old neighborhood was pressed up against the jungle border that Haiti shares with the Dominican Republic, and some of the kids he knew would slip over. Those kids would stay in the DR for a few days, sometimes weeks. Some of them never returned. But the ones who did come back wouldn’t say too much about it.

Most of them didn’t talk much at all.

By the time he was ten, Noel had learned the truth about those kids. He’d learned that they’d ended up working as prostitutes .

This was how Noel St. Pierre had learned about evil. There really were devils out in the world. Flesh-and-blood devils, and they were nothing like the demons he’d heard about in church. Noel had never forgotten the way those kids looked. The way they’d turned into old men and old women. They were like zombies trapped in children’s bodies. And now, in America, Noel’s been given a chance to help other kids.

That’s what the police have told him, at least.

Noel is a sanitation worker. Still strong at fifty, and lucky enough to have found his way to Palm Beach, he gets in to work before anyone else and keeps his white compactor truck clean, almost glistening. His pickup route runs hot and cold with the seasons. But even in the summer, with much less to do, he’s on the job early, braced for a six-hour shift that would break a lesser man’s back. In the winter, the job gets even harder. The Estate Section gets especially busy. Some of the parties have hundreds of guests. They leave behind mountains of refuse. That garbage gets picked up daily, or twice a day when requested. It’s carried by workers who slip, silently, under the porte cocheres. Then it gets whisked twenty miles away to a landfill that the garbagemen call Mount Trashmore.

Noel’s stretch of the Estate Section runs from the Everglades Club to the southernmost tip of the island. It encompasses Banyan Road, Jungle Road, El Bravo Way, and El Brillo Way. His performance record is spotless. As far as the Palm Beach PD is concerned, he’s the perfect man for the job.

Chief Reiter’s authorized a “trash pull”-a legal way to collect discarded evidence. In this case, evidence culled from Jeffrey Epstein’s garbage. But when the police call him, Noel St. Pierre simply assumes that another refugee boat has run aground on the beach. A sad thing, but something that does happen from time to time. His homeland, Haiti, is desperately poor. Run by despots who line their pockets while everyday people suffer.

Many of the refugees are illiterate.

Most of them speak only Creole.

“Eske ou ka ede nou, souple,” they ask.

“Can you help us, please?”

The cops always need a translator, and Noel’s been asked to help out before. But this time the police officer’s voice is raspy, impatient.

“This time is different,” the officer says. “Something very special. You don’t have to accept. But if you do, you’ll have to keep things to yourself, completely.”

When he hears what the story is, Noel accepts.

“I’ll do it,” he says immediately.

The address he’s been given is 358 El Brillo Way. On his first morning, St. Pierre moves swiftly, sneaking a glance through the kitchen window at the four silhouettes standing inside. Three women, one of them quite short, with pigtails.

The fourth silhouette is that of a tall man.

The police have given him clear instructions. The work is unsavory, but so is the work Noel does every day. What the detectives want from him now are slips of paper with phone numbers, along with toothbrushes, condoms, discarded underwear. Anything that could provide DNA. He’s been told to use a special truck on the El Brillo run. Whatever he finds he’s to put aside in small trash bags he’ll deliver directly to the station at the end of every shift.

Jeffrey Epstein’s garbage will never arrive at Mount Trashmore.

As he drives to the police station, St. Pierre thinks about Epstein and what he’s been told. It’s a wonder to him that American kids would do what the police say these kids have done. American kids are rich, after all. Some of them just don’t know it , he guesses.

Americans always want more than they have.

Then again, children do stupid things. They don’t know any better. And St. Pierre’s trips to the house make one thing clear. These girls are young. Really young.

“I hope you can stop this man,” St. Pierre tells the cop.

The detective shoots him a sharp look, and St. Pierre nods.

“Please,” he says, more softly this time.

“Can we count on seeing you here tomorrow?”

The detective looks antsy, impatient again. In his hand he’s holding a scrap of paper that Noel St. Pierre has pulled from Epstein’s trash. Wendy Dobbs’s name is on it. Mary’s name is on it as well.

The detective can’t wait to get it to Chief Reiter’s office.

“As long as it takes, sir,” St. Pierre tells him. “Tomorrow, the next day. Whenever you need me.”

Michael Reiter: September 2005

There’s a sense in which the Palm Beach PD functions as a foundation. From time to time, one of the town’s wealthy residents will walk in with a check followed by an inquiry. How much more would the police force need to make this remarkably safe community feel even safer?

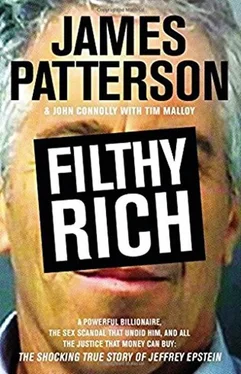

A tax write-off? Sure. But why not? Coming from most, it’s a genuine gesture. One of appreciation for all they have and for all the department’s efforts to guard it. Donations are accepted graciously, gratefully. In 2004, the department had taken one from Jeffrey Epstein-the second donation he’d made to the Palm Beach PD-for ninety thousand dollars. Generous, even by the generous standards of Palm Beach. The donation, which Epstein delivered personally, was earmarked for a firearms training simulator. But that day Michael Reiter had thought something seemed off about Epstein.

Читать дальше