We first meet Father Brown in the story “The Blue Cross,” and see him through the eyes of Valentin, described as the head of the Paris police. Valentin found himself sharing a railway carriage with a very short Roman Catholic priest going up from a small Essex village, who seemed to Valentin to be “the essence of those Eastern flats with a face as round and dull as a Norfolk dumpling and eyes as empty as the North Sea.” He had several brown-paper parcels which he was quite incapable of managing, a large shabby umbrella which constantly fell on the floor, and did not seem to know which was the right part of his return ticket. Valentin was not the only person to be taken in by this seeming innocence and simplicity.

Father Brown could not be more different from the Golden Age heroes of detective fiction. He worked alone with no routine police support, as had Lord Peter Wimsey with Inspector Parker, no Watson to provide an admiring audience and to ask questions on behalf of the less perspicacious readers, and without even Holmes’s limited scientific knowledge. He solved crimes by a mixture of common sense, observation and his knowledge of the human heart. As he says to Flambeau, the master thief whom he outwits in “The Blue Cross” and whom he restores to honesty, “Has it never struck you that a man who does next to nothing but hear men’s real sins is not likely to be wholly unaware of human evil?” There were, of course, other advantages of being a priest: he was never required to explain precisely why he was present because it was assumed that he was occupied with his priestly function, and he was a man in whom many might naturally confide.

Although we are told that Father Brown was parish priest in Cobhole in Essex before moving to London, we meet him in other and very different places, in England and overseas, and in a variety of settings and company across the whole social and economic spectrum. Nothing and no one is alien to him. We rarely encounter him in the daily routine of his pastoral duties at Cob-hole, never learn where exactly he lives, who housekeeps for him, what kind of church he has or his relationship with his bishop. We are not told his age, whether his parents are still living or even his Christian name. In each of the stories he makes his quiet appearance unannounced, as much at home with the poor and humble as he is with the rich and famous, and applying to all situations his own immutable spirituality. But he is always a rationalist with a dislike of superstition, which he sees as inimical to his faith. Like the other characters in the stories-and like us, the readers-he sees the physical facts of the case, but only he, by a process of deduction, interprets them correctly. In this he resembles, in his methods, Sherlock Holmes and Hercule Poirot. We see what is apparently obvious, however bizarre; he sees what is true. Chesterton loved paradox and, because we encounter Father Brown often in incongruous company and he comes unencumbered by his past, the little priest is himself a paradox, at once endearingly human, but also a mysterious and iconic harbinger of death.

G. K. Chesterton’s output was prodigious, and it would be unreasonable to expect all the short stories to be equally successful, but the quality of the writing never disappoints. Chesterton never wrote an inelegant or clumsy sentence. The Father Brown stories are written in a style richly complex, imaginative, vigorous, poetic and spiced with paradoxes. He had been trained as an artist and he saw life with an artist’s eye. He wanted his readers to share that poetic vision, to see the romance and numinousness in commonplace things. He brought two things in particular to detective fiction. He was among the first writers to realise that it could be a vehicle for exploring and exposing the condition of society, and for saying something true about human nature. Before he even planned the Father Brown stories, Chesterton wrote that “the only thrill, even of a common thriller, is concerned somehow with the conscience and the will.” Those words have been part of my credo as a writer. They may not be framed and on my desk but they are never out of my mind.

In Bloody Murder , published in 1972, revised in 1985 and again in 1992, a book which has become essential reading for many aficionados of crime fiction, Julian Symons suggests that because of their richness, no more than a few Father Brown short stories should be read at a time. Certainly to settle down for an evening with Father Brown would be like facing a meal composed entirely of very rich hors d’œuvres , but I have never suffered from literary indigestion when reading the stories, partly because of Chesterton’s imaginative power and his all-embracing humanity. At the end of the short story “The Invisible Man” we are told that Flambeau and the other participants in the mystery went back to their ordinary lives. “But Father Brown walked those snow-covered hills under the stars for many hours with a murderer, and what they said to each other will never be known.” We can be sure that, whatever was spoken, it had little or nothing to do with the criminal justice system.

“Your red herring. My Lord.”

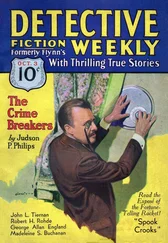

When one looks at the Golden Age in retrospect the developing rebellion against its ideas and standards is clearly visible, but this is the wisdom of hindsight, for during the thirties the classical detective story burgeoned with new and considerable talents almost every year.

Julian Symons , Bloody Murder

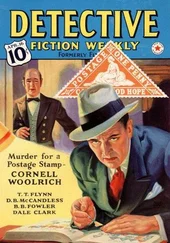

A VICTORIAN CRITIC of the Sherlock Holmes stories, writing in Blackwood’s Magazine in the late 1800s, while not altogether dismissive of the saga, concluded with the words: “Considering the difficulty of hitting on any fancies that are decently fresh, surely this sensational business must shortly come to a close.” No prophecy could have been more misjudged. Not only did the sensational business continue, but the new century saw an outburst of creative energy directed towards detective fiction, the emergence of new talented writers and a public which greeted their efforts with an avid enthusiasm which contemporary cartoons suggest amounted to a craze. Although short stories continued to be written, gradually they gave way to the detective novel. One reason for this change was probably because the writers and their increasingly enthusiastic readers preferred a longer narrative, which gave opportunities for even more complicated plotting and more fully developed characters. In the words of G. K. Chesterton, “The long story is more successful, perhaps, in one not unimportant point: that it is possible to realise that a man is alive before he is dead.” Novelists, too, if visited by a powerful idea for an original method of murder, detective or plotline, were unwilling-and indeed still are-to dissipate it on a short story when it could both inspire and form the main interest of a successful novel.

The well-known description “Golden Age” is commonly taken to cover the two decades between the First and Second World Wars, but this limitation is unduly restrictive. One of the most famous detective stories regarded as falling within the Golden Age is Trent’s Last Case by E. C. Bentley, published in 1913. The name of this novel is familiar to many readers who have never read it, and its importance is partly due to the respect with which it was regarded by practitioners of the time and its influence on the genre. Dorothy L. Sayers wrote that it “holds a very special place in the history of detective fiction, a tale of unusual brilliance and charm, startlingly original.” Agatha Christie saw it as “one of the three best detective stories ever written.” Edgar Wallace described it as “a masterpiece of detective fiction,” and G. K. Chesterton saw it as “the finest detective story of modern times.” Today some of the tributes of his contemporaries seem excessive but the novel remains highly readable, if hardly as compelling as it was when first published, and its influence on the Golden Age is unquestionable. E. C. Bentley, who wrote the book between 1910 and 1912, was a lifelong friend and fellow journalist of G. K. Chesterton and probably wrote the novel with Chesterton’s encouragement. But what Bentley produced was hardly what his friend would have expected. Seeing himself as a modernist, Bentley disliked the conventional straitjacket of the orthodox detective story and had little respect for Sherlock Holmes. He planned a small act of sabotage, a detective story which was to satirize rather than celebrate the genre. It is ironic that although his hero, Trent, doesn’t solve the murder-nor of course did Sergeant Cuff in The Moonstone -Bentley is seen as an innovator, not a destroyer of the detective story.

Читать дальше