When you investigate the vistas of time, you find something very similar. Because it is clear from the fossil record that almost every species that has ever existed is extinct; extinction is the rule, survival is the exception. And no species is guaranteed its tenure on this planet. I would like to describe to you one event that I've already referred to as central to the origin of the human species, because it is connected with the main topic of this talk. This is the worldwide extinction event that happened 65 million years ago, at the boundary between the Cretaceous and Tertiary periods of geological time, which also corresponds to the end of the Mesozoic age and the beginning of more recent times.

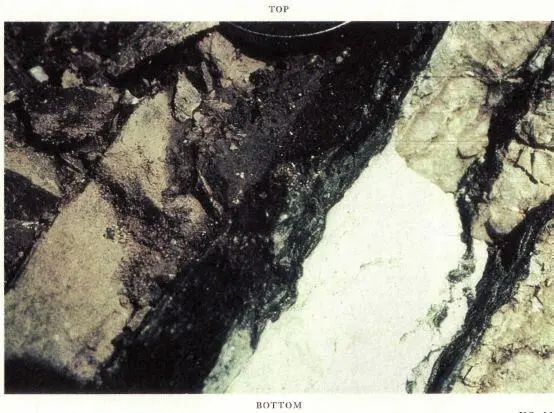

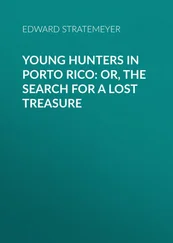

This is a close-up of a cliff base on a roadside near Gubbio in northern Italy. You can make out the scale of the image from the edge of a five-hundred-lire piece right up at the top. The surface crust has been scraped away a little bit, and the white material is calcium carbonate, essentially chalk, similar to the composition of the White Cliffs of Dover. These are the remains of countless small microorganisms that lived in the Cretaceous seas, forming little calcium carbonate shells that slowly fell through the warm waters of those seas and built up, during

fig. 35

Cretaceous time, for many millions of years. This deposit, as you can see, comes to an abrupt end. Time is increasing toward upper left. A layer of reddish brown rock lies above the older white carbonate, separated by a sharp boundary. And it's below this boundary that you find the last dinosaurs, and above the boundary you find an astonishing rate of proliferation of the small mammals into larger mammals, the events that are prerequisite for our own origins.

The sharpness of this boundary worldwide suggests some quite recent catastrophic event. The boundary is that thin layer of gray clay running diagonally across the picture. The clay- this is also true worldwide-has a quite high concentration, an anomalously high concentration, of a chemical element called iridium and other elements like it in the platinum group of metals. It is known that asteroids, and presumably cometary nuclei as well, have much higher abundances of iridium than do ordinary rocks on the Earth. And this iridium anomaly, now supported by a wide range of other data, is generally taken to be evidence for what happened to extinguish the dinosaurs and most of the other species of life on the Earth 65 million years ago.

This is an artist's conception of an object, maybe an asteroid, maybe a cometary nucleus, impacting the Cretaceous oceans. It's about ten kilometers across. It is bigger than the thickness of the ocean, so it is the same as impacting on land. The net result is to carve out in the ocean floor an immense crater and propel the fine particles thus generated into high orbit, making a vast

fig. 36

cloud of pulverized ocean bottom and pulverized impacting object that takes some years to settle out from the Earth's high atmosphere. During that period of time, sunlight is impeded from reaching the surface of the Earth, and the net result is a darkened and cold surface worldwide, which led, because of the differences in mammalian and reptilian physiology, to the extinction of the dinosaurs and many other kinds of life.

That is what happened to the dinosaurs. They were powerless to anticipate it and certainly to prevent it. What I would like now to describe is a catastrophe that in some respects is quite similar, one that endangers the future of our own species. It is very different in one respect: Unlike the dinosaurs, we ourselves, at enormous cost in treasure, have created this danger. We are solely responsible for its existence, and we have the means of preventing it, if we are sufficiently courageous and sufficiently willing to reconsider the conventional wisdom. That problem is nuclear war.

The bombs that destroyed Hiroshima and Nagasaki-everybody's read about them, we know something about what they did-killed some quarter of a million people, making no distinctions according to age, sex, class, occupation, or anything else. The planet Earth today has fifty-five thousand nuclear weapons, almost all of which are more powerful than the bombs that destroyed Hiroshima and Nagasaki and some of which are, each of them, a thousand times more powerful. [7]Some twenty to twenty-two thousand of these weapons are called strategic weapons, and they are poised for as rapid delivery as possible, essentially halfway across the world to someone else's homeland.

The ballistic missiles are sufficiently capable that typical transit times are less than half an hour. Twenty thousand strategic weapons in the world is a very large number. For example, let's ask how many cities there are on the planet Earth. If you define a city as having more than one hundred thousand people in it, there are twenty-three hundred cities on the Earth. So the United States and the Soviet Union could, if they wished, destroy every city on the Earth and have eighteen thousand strategic weapons left over to do something else with.

It is my thesis that it is not only imprudent but foolish to an extreme unprecedented in the events of the human species to have so large an arsenal of weapons of such destructive power simply available. Now, the prompt effects of nuclear war are reasonably well known. I will say a few words about them, but I want to concentrate mainly on the more recently discovered, more poorly known, delayed longer-term and global effects.

Imagine the destruction of New York City by two one-megaton nuclear explosions in a global war. You could choose any other city on the planet, and in a nuclear war you can be reasonably confident that that city would suffer some similar fate. Starting at the World Trade Center and continuing about ten miles in all directions, the effects would play out. You know about the fireball and the shock waves, the prompt neutrons and gamma rays, the fires, the collapsing buildings, the sorts of thing that were responsible for most of the deaths at Hiroshima and Nagasaki. But the bomb light also sets fires, some of which are blown out by the shock wave as the mushroom cloud rises. Others are not.

And these conflagrations can grow. And in many cases, although certainly not all, the conflagrations merge to produce a firestorm. Recent work suggests that firestorms should be much more common and much more severe than had been expected in earlier research, producing the kind of fire as in a well-tended fireplace with an excellent draft. The net result, as advertised: No cities are left standing. But that's the least of the problem.

Beyond the obliteration of the cities is the production of a pall of sooty smoke sitting not just above the city but carried by the fire to quite high altitudes, where this dark smoke is heated by the Sun, which then makes it expand still more. This happens, obviously, not just above one target but above many or most targets.

Cities and petrochemical facilities would be preferentially targeted. Prevailing winds would blow the fine particles in the same direction, from west to east. In anything like a full exchange something like ten thousand nuclear weapons would be detonated.

Some ten days later, there would still be a few nuclear explosions from, I don't know, nuclear-submarine commanders who have not been told that the war was over. The smoke and dust would circulate all around the planet in longitude and spread poleward and equatorward in latitude. The Northern Hemisphere would be almost entirely socked in with smoke and dust. You would see outriders, plumes of smoke in the Southern Hemisphere. The cloud would then cross the equator well into the Southern Hemisphere. And while the effects would be somewhat less in the Southern Hemisphere, sunlight would dim and the temperatures would fall there as 'well.

Читать дальше