"If this strange idea occurred to you, of asking me to make cuts, it must be that you personally find the sequence of movements in Jeu de cartes a little boring. I cannot do anything about that. But what amazes me most is that you try to convince me to make cuts in it-me, who just conducted it in Venice and who reported to you the enthusiastic response of the audience. Either you forgot what I told you, or else you do not attach much importance to my observations or to my critical sense. Furthermore, I really do not believe that your audience would be less intelligent than the one in Venice.

"And to think that it is you who proposed to cut my composition, with every likelihood of distorting it, in order that it might be better understood by the public-you, who were not afraid to play a work as risky from the standpoint of success and listener comprehension as the Symphonies of Wind Instruments!

"So I cannot let you make cuts in Jeu de cartes: I think it is better not to play it at all than to do so with reservations.

"I have nothing to add, period."

On October 15, Ansermet's reply:

"I ask only if you would forgive me the small cut in the March from the second measure after 45 to the second measure after 58."

Stravinsky reacted on October 19:

"… I am sorry, but I cannot allow you any cuts in Jeu de cartes.

"The absurd one that you propose cripples my little March, which has its form and its structural meaning in the totality of the composition (a structural meaning that you claim to be protecting). You cut my March only because you like the middle section and the development less than the rest. In my view, this is not sufficient reason, and I would like to say: 'But you're not in your own house, my dear fellow'; I never told you: "Here, take my score and do whatever you please with it.'

"I repeat: either you play Jeu de cartes as it is or you do not play it at all.

"You do not seem to have understood that my letter of October 14 was quite categorical on this point."

Thereafter they exchanged only a few letters, chilly, laconic. In 1961 Ansermet published in Switzerland a voluminous book of musicology, including a lengthy chapter that is an attack on the insensitivity of Stravinsky's music (and his incompetence as a conductor). Only in 1966 (twenty-nine years after their dispute) was there this brief response from Stravinsky to a conciliatory letter from Ansermet:

"My dear Ansermet,

"Your letter touched me. We are both too old not to think about the end of our days; and I would not want to end these days with the painful burden of an enmity."

An archetypal phrase for an archetypal situation:

often toward the end of their lives, friends who have failed one another will call off their hostility this way, coldly, without quite becoming friends again.

It's clear what was at stake in the dispute that wrecked the friendship: Stravinsky s authors rights, his moral rights; the anger of an author who will not stand for anyone tampering with his work; and, on the other side, the annoyance of a performer who cannot tolerate the authors proud behavior and tries to limit his power.

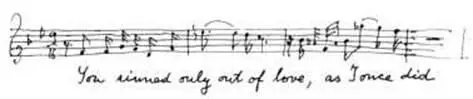

As I listen to Leonard Bernstein's recording of he Sacre du printemps, something seems odd about the famous lyrical passage for E-flat clarinet in the " Rondes print-anieres "; I turn to the score:

In Bernstein's performance, this becomes:

The novel charm of the passage above lies in the tension between the melodic lyricism and the rhythm, which is both mechanical and weirdly irregular; if this rhythm is not executed exactly, with clockwork precision, if it is rubatoed, if the last note of each phrase is stretched out (which Bernstein does), the tension disappears and the passage becomes commonplace.

I think of Ansermet's sarcasms. I prefer Stravinsky's performance, a hundred times over, even if he does push "his music stand up against the podium rail… and counts time."

In his book on Janacek, Jaroslav Vogel, himself a conductor, discusses Kovarovic's alterations to the score of Jenufa. He approves them and defends them. An astonishing attitude, for even if Kovarovics alterations were useful, good, or sensible, they are unacceptable in principle, and the very idea of arbitrating between a creators version and one by his corrector (censor, adapter) is perverse. Without a doubt, this or that sentence of A la recherche du temps perdu could be better written. But where could you find the lunatic who would want to read an improved Proust?

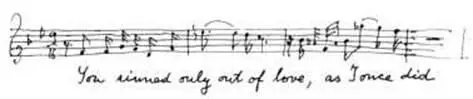

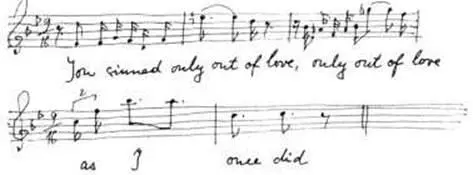

Besides, Kovarovics alterations are anything but good or sensible. As proof of their soundness, Vogel cites the last scene of the opera, where, after the discovery of her murdered child and the arrest of her stepmother, Jenufa is alone with Laca. Jealous of her love for Steva, his half-brother Laca had earlier slashed Jenufa's face; now Jenufa forgives him: it was

out of love that he had injured her, just as she herself had sinned out of love:

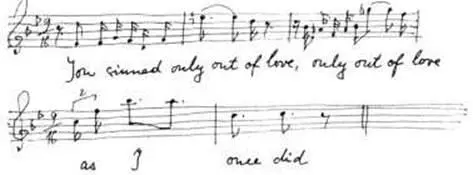

The allusion to her love for Steva, "as I once did," is delivered very rapidly, like a short cry, in high notes that rise and break off; as if Jenufa is evoking something she wants to forget immediately. Kovarovic broadens the melody of this passage (he "makes it bloom," as Vogel says) by transforming it like this:

Doesn't Jenufa's song, asks Vogel, become more beautiful under Kovarovic's pen? And isn't it still completely Janacekian? Yes, if you wanted to fake Janacek, you couldn't do better. Nonetheless, the added melody is absurd. Whereas in Janacek, Jenufa recalls her "sin" rapidly, with suppressed horror, in Kovarovic she grows tender at the recollection, she lingers over it, she is moved by it (her song stretches out the words "love," "I," and "once did"). So there to Laca's face she sings of her yearning for Steva, Laca's rival-she sings of her love for Steva, the cause of all her misery!

How could Vogel, a passionate supporter of Janacek's, defend such psychological nonsense? How could he sanction it, when he knew that Janacek's aesthetic rebellion is rooted precisely in his rejection of the psychological unrealism current in opera practice? How is it possible to love someone and at the same time misunderstand him so completely?

Still-and here Vogel is right-by making the opera a little more conventional, Kovarovic's alterations did contribute to its success. "Let us distort you a bit, Maestro, and they'll love you." But there comes a time when the maestro refuses to be loved at such cost and would rather be detested and understood.

What means does an author have at his disposal to make himself understood for what he is? Hermann Broch hadn't many in the 1930s and in an Austria cut off from Germany turned fascist, nor later on in the loneliness of emigration: a few lectures explaining his aesthetic of the novel; then letters to friends, to his readers, to his publishers, to his translators; he left nothing undone, taking great care, for instance, over the copy on his book jackets. In a letter to his publisher, he protests a proposal for a promotional line on the back cover of his novel The Sleepwalkers that would compare him to Hugo von Hofmannsthal and Italo Svevo. His counterproposal: that he be compared to Joyce and Gide.

Читать дальше