Blaine Harden

ESCAPE FROM CAMP 14

One Man’s Remarkable Odyssey from North Korea to Freedom in the West

For North Koreans who remain in the camps

‘There is no “human rights issue” in this country, as everyone leads the most dignified and happy life.’

[North] Korean Central News Agency, 6 March 2009

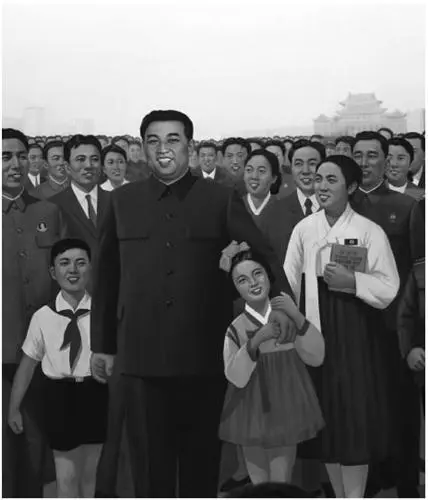

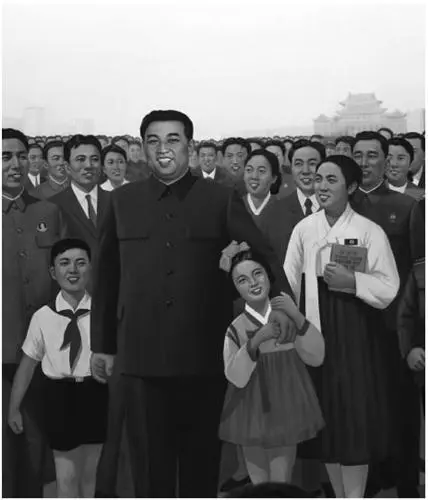

The cult of personality surrounding the Kim family began with the Great Leader, Kim Il Sung, who was depicted in government propaganda as a loving father to his people. Although his leadership was brutal, his death in 1994 was deeply mourned.

(Photo of painting by Blaine Harden)

His first memory is an execution.

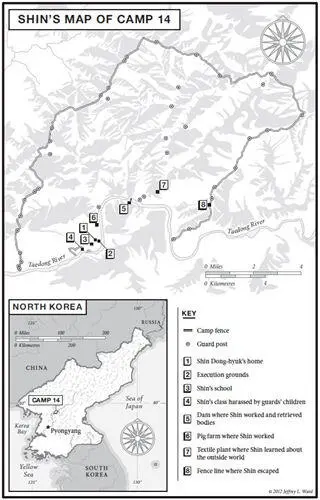

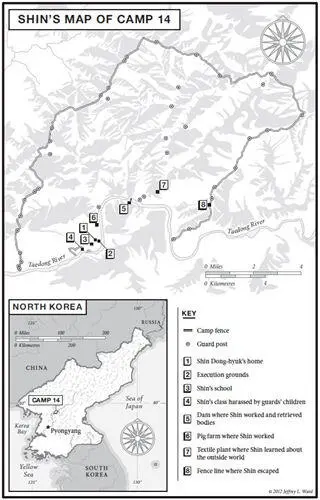

He walked with his mother to a wheat field near the Taedong River, where guards had rounded up several thousand prisoners. Excited by the crowd, the boy crawled between adult legs to the front row, where he saw guards tying a man to a wooden pole.

Shin In Geun was four years old, too young to understand the speech that came before that killing. At dozens of executions in years to come, he would listen to a supervising guard telling the crowd that the prisoner about to die had been offered ‘redemption’ through hard labour, but had rejected the generosity of the North Korean government. To prevent the prisoner from cursing the state that was about to take his life, guards stuffed pebbles into his mouth then covered his head with a hood.

At that first execution, Shin watched three guards take aim. Each fired three times. The reports of their rifles terrified the boy and he fell over backwards. But he scrambled to his feet in time to see guards untie a slack, blood-spattered body, wrap it in a blanket and heave it into a cart.

In Camp 14, a prison for the political enemies of North Korea, assemblies of more than two inmates were forbidden, except for executions. Everyone had to attend them. The labour camp used a public killing, and the fear it generated, as a teachable moment.

Shin’s guards in the camp were his teachers — and his breeders. They had selected his mother and father. They taught him that prisoners who break camp rules deserve death. On a hillside near his school, a slogan was posted: ‘All according to the rules and regulations’. The boy memorized the camp’s ten rules, ‘The Ten Commandments’, as he later called them, and can still recite them by heart. The first one stated: ‘Anyone caught escaping will be shot immediately’.

Ten years after that first execution, Shin returned to the same field. Again, guards had rounded up a big crowd. Again, a wooden pole had been pounded into the ground. A makeshift gallows had also been built.

Shin arrived this time in the backseat of a car driven by a guard. He wore handcuffs and a blindfold fashioned from a rag. His father, also handcuffed and blindfolded, sat beside him in the car.

They had been released after eight months in an underground prison inside Camp 14. As a condition of their release, they had signed documents promising never to discuss what had happened to them underground.

In that prison within a prison, guards tried to torture a confession out of Shin and his father. They wanted to know about the failed escape of Shin’s mother and only brother. Guards stripped Shin, tied ropes to his ankles and wrists, and suspended him from a hook in the ceiling. They lowered him over a fire. He passed out when his flesh began to burn.

But he confessed nothing. He had nothing to confess. He had not conspired with his mother and brother to escape. He believed what the guards had taught him since his birth inside the camp: he could never escape and he must inform on anyone who talked about trying. Not even in his dreams had Shin fantasized about life on the outside.

The guards never taught him what every North Korean schoolboy learns: Americans are ‘bastards’ scheming to invade and humiliate the homeland. South Korea is the ‘bitch’ of its American master. North Korea is a great country whose brave and brilliant leaders are the envy of the world. Indeed, he knew nothing of the existence of South Korea, China, or the United States.

Unlike his countrymen, he did not grow up with the ubiquitous photograph of his Dear Leader, as Kim Jong Il was called. Nor had he seen photographs or statues of Kim’s father, Kim Il Sung, the Great Leader who founded North Korea and who remains the country’s Eternal President, despite his death in 1994.

When a guard removed his blindfold and he saw the crowd, the wooden pole and the gallows, Shin believed he was about to be executed.

No pebbles, though, were forced into his mouth. His handcuffs were removed. A guard led him to the front of the crowd. He and his father would be spectators.

Guards dragged a middle-aged woman to the gallows and tied a young man to the wooden pole. They were Shin’s mother and his older brother.

A guard tightened a noose around his mother’s neck. She tried to catch Shin’s eye. He looked away. After she stopped twitching at the end of the rope, Shin’s brother was shot by three guards. Each fired three times.

As he watched them die, Shin was relieved it was not him. He was angry with his mother and brother for planning an escape. Although he would not admit it to anyone for fifteen years, he knew he was responsible for their executions.

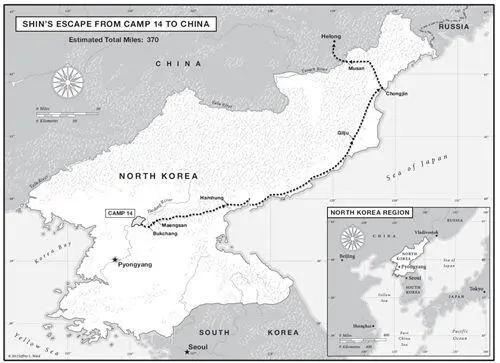

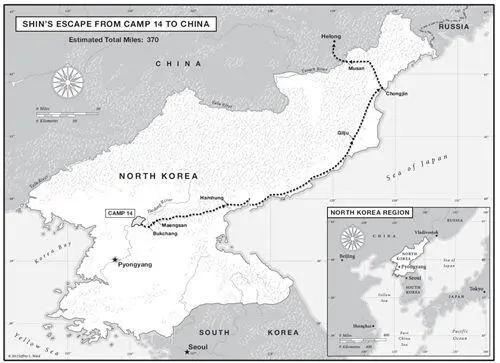

Nine years after his mother’s hanging, Shin squirmed through an electric fence and ran off through the snow. It was 2 January 2005. Before then, no one born in a North Korean political prison camp had ever escaped. As far as can be determined, Shin is still the only one to do so.

He was twenty-three years old and knew no one outside the fence.

Within a month, he had walked into China. Within two years, he was living in South Korea. Four years later, he was living in southern California and was a senior ambassador at Liberty in North Korea (LiNK), an American human rights group.

His name is now Shin Dong-hyuk. He changed it after arriving in South Korea in an attempt to reinvent himself as a free man. He is handsome, with quick, wary eyes. A Los Angeles dentist has done work on his teeth, which he could not brush in the camp. His overall physical health is excellent. His body, though, is a roadmap of the hardships of growing up in a labour camp that the North Korean government insists does not exist.

Stunted by malnutrition, he is short and slight — five feet six inches and about one hundred and twenty pounds. His arms are bowed from childhood labour. His lower back and buttocks are scarred with burns from the torturer’s fire. The skin over his pubis bears a puncture scar from the hook used to hold him in place over the fire. His ankles are scarred by shackles, from which he was hung upside down in solitary confinement. His right middle finger is cut off at the first knuckle, a guard’s punishment for dropping a sewing machine in a camp garment factory. His shins, from ankle to knee on both legs, are mutilated and scarred by burns from the electrified barbed-wire fence that failed to keep him inside Camp 14.

Shin is roughly the same age as Kim Jong Eun, the chubby third son of Kim Jong Il who took over as leader after his father’s death in 2011. As contemporaries, Shin and Kim Jong Eun personify the antipodes of privilege and privation in North Korea, a nominally classless society where, in fact, breeding and bloodlines decide everything.

Читать дальше