EGMONT PRESS: ETHICAL PUBLISHING

Egmont Press is about turning writers into successful authors and children into passionate readers – producing books that enrich and entertain. As a responsible children’s publisher, we go even further, considering the world in which our consumers are growing up.

Safety FirstNaturally, all of our books meet legal safety requirements. But we go further than this; every book with play value is tested to the highest standards – if it fails, it’s back to the drawing-board.

Made FairlyWe are working to ensure that the workers involved in our supply chain – the people that make our books – are treated with fairness and respect.

Responsible ForestryWe are committed to ensuring all our papers come from environmentally and socially responsible forest sources.

For more information, please visit our website at www.egmont.co.uk/ethical

Egmont is passionate about helping to preserve the world’s remaining ancient forests. We only use paper from legal and sustainable forest sources, so we know where every single tree comes from that goes into every paper that makes up every book.

This book is made from paper certified by the Forestry Stewardship Council (FSC), an organisation dedicated to promoting responsible management of forest resources. For more information on the FSC, please visit www.fsc.org . To learn more about Egmont’s sustainable paper policy, please visit www.egmont.co.uk/ethical .

Also by Michael Morpurgo

Arthur: High King of Britain

Friend or Foe

The Ghost of Grania O’Malley

Kensuke’s Kingdom

King of the Cloud Forests

Little Foxes

Long Way Home

Mr Nobody’s Eyes

My Friend Walter

The Nine Lives of Montezuma

The Sandman and the Turtles

The Sleeping Sword

Twist of Gold

Waiting for Anya

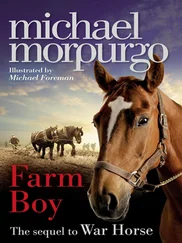

War Horse

The War of Jenkins’ Ear

The White Horse of Zennor

The Wreck of Zanzibar

Why the Whales Came

For Younger Readers

Conker

Mairi’s Mermaid

The Best Christmas Present in the World

The Marble Crusher

For Conrad and Anne

1 A bit of old goat

2 Water music

3 Barnardo’s boys

4 The prodigal father

5 Nowhere man

6 And all shall be well

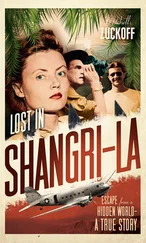

7 Shangri-La

8 The Lucie Alice

9 Gone missing

10 Dunkirk

11 The great escape

12 Earlie in the morning

13 Message to my father

I WAS KNEELING UP AGAINST THE BACK OF THE sofa looking out of the window. Summer holidays and raining, raining streams. ‘He’s been there all day,’ I said.

‘Who has?’ My mother was still doing the ironing. ‘I don’t know why,’ she went on, ‘but I love ironing. Therapeutic, restorative, satisfying. Not like teaching at all. Teaching’s definitely not therapeutic.’ She talked a lot about teaching, even in the holidays.

‘That man. He just stands there. He just stands there staring at us.’

‘It’s a free world, isn’t it?’

The old man was standing on the opposite side of the road outside Mrs Martin’s house underneath the lamppost. Sometimes he’d be leaning up against it, and sometimes he’d be just standing there, shoulders hunched, his hands deep in his pockets. But always he’d be looking, looking right at me. He was wearing a blue donkey jacket – or perhaps it was a sailor’s jacket, I couldn’t tell – the collar turned up against the rain. His hair was long, long and white, and it seemed to be tied up in a ponytail behind him. He looked like some ancient Viking warlord.

‘Come and see,’ I said. ‘He’s strange, really strange.’ But she never even looked up. How anyone could be so obsessively absorbed in ironing was beyond me. She was patting the shirt she’d finished, sadly, her head on one side, just as if she was saying goodbye to an old dog. I turned to the window again.

‘What’s he up to? He must be soaked. Mum!’ At last she came over. She was kneeling beside me on the sofa now and smelling all freshly ironed herself. ‘All day, he’s been there all day, ever since breakfast. Honest.’

‘All that hair,’ she tutted. ‘He looks a bit of a tramp if you ask me, a bit of an old goat.’ And she wrinkled up her nose in disapproval, as if she could smell him, even from this far away.

‘And what’s wrong with tramps, then?’ I said. ‘I thought you said it was a free world.’

‘Free-ish, Cessie dear, only free-ish.’ And she leant across me and closed the curtains. ‘There, now he can look at the back of our William Morris lily pattern to his heart’s content, and we don’t have to look at him any more, do we?’ She smiled her ever so knowing smile at me. ‘Do you think I was born yesterday, Cessie Stevens? Do you think I don’t know what this is all about? It’s the “p” word, isn’t it? Pro . . . cras . . . tin . . . ation.’ She was right of course. She enunciated it excruciatingly slowly, deliberately teasing the word out for greatest effect. She was expert at it. My mother wasn’t a teacher for nothing. ‘Violin practice, Cessie. First you said you’d do it this morning, then you were going to do it this afternoon. And now it’s already this evening and you still haven’t done it, have you?’

She was off the sofa now and crouching down in front of me, looking into my face, her hands on mine. ‘Come on. Before your dad gets home. You know how it upsets him when you don’t practise. Be an angel.’

‘I am not an angel,’ I said firmly. ‘And I don’t want to be an angel either.’ I was out of the room and up the stairs before she could say another word.

I was ambivalent about my mother. I was closer to her than anyone else in this world. She had always been my only confidant, my most trusted friend. Whatever I did, she would always defend me to the hilt. I’d overhear her talking about me. ‘She’s just going through that awkward prickly stage,’ she’d explain. ‘Half girl, half woman. Not the one thing, nor the other. She’ll come out of it.’ But sometimes she just couldn’t stop playing teacher. Worst of all, she would use my father as a weapon against me. In fact, my father was never really upset when I didn’t practise my violin, but I knew that he would be disappointed. And I hated to disappoint him – she knew that too.

Whenever he could, whenever he was home, my father would come up to my room to hear me play. He’d sit back in my chair, put his hands behind his head and close his eyes. When I played well – and I usually did when he was there – he would give me a huge bear hug afterwards, and say something like, ‘Eat your heart out, Yehudi.’ But just recently, ever since we moved house, my father hadn’t been able to hear me that much. His new job at the radio station kept him busier than ever – he had two shows a day and some at weekends too. I’d listen in from time to time just to hear his voice, but it was never the same. He was never my father on the radio.

Читать дальше