Scott MacDonald - A Critical Cinema 2 - Interviews with Independent Filmmakers

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Scott MacDonald - A Critical Cinema 2 - Interviews with Independent Filmmakers» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 1992, ISBN: 1992, Издательство: University of California Press, Жанр: Прочая документальная литература, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:A Critical Cinema 2: Interviews with Independent Filmmakers

- Автор:

- Издательство:University of California Press

- Жанр:

- Год:1992

- ISBN:9780585335100

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

A Critical Cinema 2: Interviews with Independent Filmmakers: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «A Critical Cinema 2: Interviews with Independent Filmmakers»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

A Critical Cinema 2: Interviews with Independent Filmmakers — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «A Critical Cinema 2: Interviews with Independent Filmmakers», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

69

undoes itself. It starts out like a system, then the system breaks down and goes to hell. During the editing I came up with the idea that it should break down, so I shuffled the cards. I thought it served me right to undo my own pretense at formal purity.

MacDonald:

When exactly did you shuffle the cards?

Breer:

First I shot each sequence several times. I was thinking of serial repetitions and building a texture. But I got bored with that, so I said "What if." I started shuffling the cards and shooting them in random sequences and shuffling more and more.

Also, there were some accidents. This was before dimmers were available and I had a parallel circuit for the lights and a double-throw switch, so I could put them on half-light (Stan Vanderbeek had shown me how to do that). I shot a sequence on the low light by accident, and it was brown and dismal looking, but somewhere during that scene I had turned the lights on for a second and there was a flash of proper lighting embedded within this dark stuff. Instead of dismissing all that material, I took advantage of it in the best tradition of experimental filmmaking. I went back and deliberately shot a lot of stuff at half-light, with a few sprinklings of properly lit imagery.

MacDonald:

You're very early in experimenting with flicker effects. They're an element in some of the earliest films, and you come back to flicker often.

Breer:

If you question everything, you'll question why you have to eliminate flicker. Flicker is disturbing, but it has an impact, and it doesn't make you have flat feet, or burn your retina. It's just another tool we've overlooked. I question all the time. It started out with my questioning the existence of God when I was a little kid. I read something by Sinclair Lewis when I was twelve or thirteen years old and challenged God to strike me dead. I gave him about fifteen minutes, thinking if he was all that powerful, that'd be plenty of time. And nothing happened, and I went down and told my parents I wasn't going to church anymore. I never had believed in God, but I'd been too scared to announce it. Of course, I had some awful experiences as a little kid at Catholic school, so I already had bad vibes about religion. But I questioned and got away with it.

In film a lot of things have been repressed for so long that they're fresh. I explore the medium for that kind of thing. There's an awful lot

Page 44

of conformism. That's the natural tendency, just for the sake of convenience and safety. You learn what doesn't kill you; you play it safe. But when it comes to art, you can do stuff that'll "kill" you. A basic example of that is the oscillation of light and dark in the projector. Of course, the modern cinema device was designed to eliminate flicker, but you can bring it back and play around with it.

MacDonald:

During the late sixties you began to make a new kind of kinetic sculptureWhat you call "floats." How do you see them relating to your film work?

Breer:

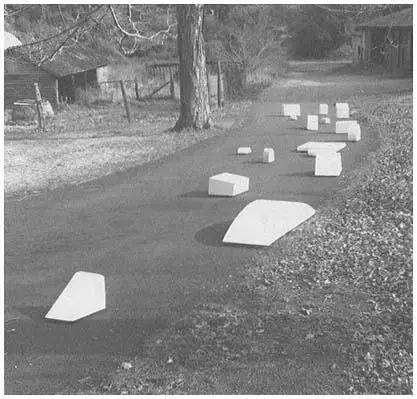

In my films, I deal with a medium designed for motion and bring it to a point where things go by so fast that they start standing still: the interruption of continuity is so great that finally there isn't much, if any, continuity, and I have what amounts to a static picture where everything is on the brink of flowing into motion but never quite does. With the floats, it's the same and in another sense the opposite. Sculptures are "not supposed" to move, but these do, just barely. In each case I'm challenging the limits of the medium, or confusing the expectations that one might normally have.

And there's something more to it. Since childhood model airplane days, I've always had a great satisfaction in putting things together, pounding nails, sawing wood, sandpapering. My brain had gotten me into a kind of painting that didn't have a hell of a lot to it past the conceptual stage. In my geometric paintings I just had to cover vast areas of canvas: it was like house painting. When I started doing films, there was a lot more involvement with making things. There was the camera apparatus itself, and making thousands of images for a film put a demand on my imagination that doing one painting didn't. Starting to make sculptures had a workshop satisfaction that filmmaking didn't. It got me involved in the world of switches, wheels, electricity. It made me feel good. I could even listen to the radio when I worked. And I got high on the idea that when I was through with them, these things had their own autonomy. I didn't think I was Pygmalion, but the idea of making art objects that were restless was intriguing to me. I was trying to create a sort of gallery presence with them and didn't want their activities reduced to anecdotal events, so that people would wait to see what happened when they bumped into each other. But I did get a certain pleasure in the unconventional behavior (in any behavior at all!) of these art objects.

One collector who was being persuaded to buy one of the floats was very worried. She asked me what would happen if one of them went across the room and ran into one of her paintings. Bob Rauschenberg, who did buy a bunch of them, was worried that his dog would take after them, but his dog never showed any interest at all. There were some

Page 45

Breer's floats on the move.

junior high kids who used to come to the gallery after school. They'd lie down on the floor of the gallery and wait until the floats would nudge up to them. Those kids understood that the floats were atmospheric, which was the point as far as I'm concerned.

MacDonald:

Why did you start working with the rotoscope in

Gulls and Buoys?

Breer: Gulls and Buoys

started in the South of France. We took four kids down to an apartment in a chateau that we rented for eighty dollars a week. I was supposed to be on vacation for once. I had gotten this heavy number about not always working, but I still wanted to. The place was very bare. There was a desk and a desk lamp. The desk had a deep drawer, and I put the lamp in it and made a light table with a piece of broken glass. I bought cards in a little stationary store. I'd buy them out every dayfifty cards. I just started drawing. I outlined my hand, and then I took the key out of the desk and outlined that. I guess from that I

Page 46

got the idea that since I'm outlining the reality anyway, I could do the same thing with a projected image. When I got back to the States, I dug up this footage of gulls I'd shot from the back of a ferry boat, and the footage of swans. It was all good stuff I had shot when I was trying to make a film after I did the NBC thing for Brinkley. I'd gotten a lot of 7252 stock, but I was so ignorant that I couldn't get the lighting right and the stuff looked flat. Of course 7252 stock does look flat in the original. It's only a printing stock. But I was very slow coming to this, and I was so disappointed in the live action material that I abandoned the whole project. Anyhow, I decided I'd use that footage, but that I could draw those gulls better than I'd photographed them. For the rotoscoping I just remade my old Craig viewer. I took the top off it and enlarged the screen to four by six, bought index cards that would fit, and started tracing and cranking through the images one at a time. It was very crude. I couldn't see the gulls sharply at all and realized that it would be silly to pursue it in too much detail. I decided to be sketchy about it and assume that the general movement would show. I could enjoy myself with drawing for a change and not have to worry about the relationships from one image to the next.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «A Critical Cinema 2: Interviews with Independent Filmmakers»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «A Critical Cinema 2: Interviews with Independent Filmmakers» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «A Critical Cinema 2: Interviews with Independent Filmmakers» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.