Scott MacDonald - A Critical Cinema 2 - Interviews with Independent Filmmakers

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Scott MacDonald - A Critical Cinema 2 - Interviews with Independent Filmmakers» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 1992, ISBN: 1992, Издательство: University of California Press, Жанр: Прочая документальная литература, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:A Critical Cinema 2: Interviews with Independent Filmmakers

- Автор:

- Издательство:University of California Press

- Жанр:

- Год:1992

- ISBN:9780585335100

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

A Critical Cinema 2: Interviews with Independent Filmmakers: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «A Critical Cinema 2: Interviews with Independent Filmmakers»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

A Critical Cinema 2: Interviews with Independent Filmmakers — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «A Critical Cinema 2: Interviews with Independent Filmmakers», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Page 36

MacDonald: Breathing

is a tour de force of drawing. It reminds me of Lye's scratched imagery in

Free Radicals

[1958] and of the directly scratched jazz passage in the middle of [Norman] McLaren's

Hen Hop

[1942].

Breer:

I was sent a copy of

Hen Hop

in 35mm, and I turned it into a mutoscope as a gift to McLaren for this big tribute they had for him in Canada. I cut up his hen so it hipped more than it hopped.

Breathing

is 35mm. I drew the whole thing, and then shot it in 16mm several times, until I got all of the images lined up in their proper order. I didn't want to waste the 35mm time.

MacDonald:

Why did you make this particular film in 35mm?

Breer:

Because I wanted absolutely the sharpest, best image I could get. I wanted to do

A Man and His Dog Out for Air

better.

Breathing

is kind of a throwback in that sense. I wanted to use high contrast film and the sharpest lens possible and the most stable camera. The drawback with my Bolex windup camera is that the shutter exposures are not consistent; there are slight variations, flicker. Shooting in 35mm gives you just that much more resolution. I wanted a super slick film for very simple drawing. I used soundtrack film, which is absolute black or white, and I rented a 35mm Oxbury for a day, at ten dollars an hour, which seemed like a hundred dollars an hour at the time, from Al Stahl, who had about six of them in a row down at 1600 Broadway. I went in there one morning with boxes of cards and by nighttime I'd shot eight thousand of them. I couldn't stand. I couldn't walk. But when I got the film back, I had to make only one cut. The result was so good that the film was used to focus the projectors at Lincoln Center.

When I started making that film, we were in this little summer house in Rhode Island. I'd rented a barn space. I put a sign on the wall, saying "This film is what it is what it is." In fact I had several of those signs on the walls to keep me on target and not allow me to digress from line drawing into craziness.

MacDonald:

At times, it's hard to believe that the imagery isn't rotoscoped.

Breer:

I didn't know from rotoscoping. I do remember the exquisite pleasure in taking a flat line and making it come at you. Rudy Burckhardt mentioned to me one time that that was his favorite film of mine, and especially when that elbow shape suddenly comes into 3-D and swings around.

MacDonald:

That's the movement that reminded me of

Free Radicals

.

Breer:

Lye made

Free Radicals

by laying the strips out on a table and scratching and listening to the music. He didn't have the advantage I had of being able to see consecutive images, so his film really is a tour de

Page 37

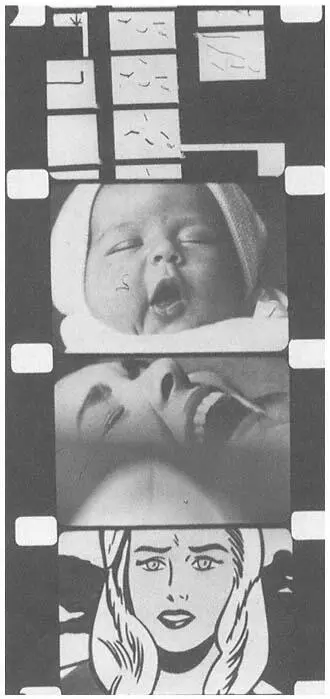

Successive frames from Breer's

Fist Fight

(1964).

Page 38

force. He was so sure of his continuity that he didn't have to see it, though he must have played it back to himself on a viewer or something.

MacDonald: Fist Fight

seems like a personal scrapbook.

Breer:

It started out as an openly souvenir film, using family memorabilia. I had seen some of the personal films people had made, and I decided I could deal with my own personal material unsentimentally, that it would be a challenge to use family snapshots and items from my own life and yet to keep the film cold and publicto have it both ways, in other words. Then I got sidetracked by [Karlheinz] Stockhausen. He wanted me to make a film for his theater piece

Originale

. I'd shot and edited most of

Fist Fight

by then. He had a scenario that required a little preface to the film which would consist of snapshots of the people in the theater piece, so I decided I would turn this film into his film. I asked all the participants to send me snapshots of themselves, and that's how the finished film starts, with Stockhausen himself upside down on the screen, then all the people in the performance: Nam June Paik, Charlotte Moorman, Alvin Lucier, David Berman, and Mary Lucier, all in bed together with a blanket pulled up to their chins, Letty Lou Eisenhouer, Max Newhaus, Alan Kaprow, and Olga Klüver. I made a composition out of all those stills, moving them and blowing smoke across them, spinning them around and so forth. That preface stopped the film from being a personal film in terms of content, although snapshots of my brothers and myself appear later.

At the Stockhausen performance, my role called for me to open up the scene with closed-circuit television. I had a video camera, and we had two monitors in the audience. As people came in, I shot them so they could see themselves on the screens. That got the audience involved right away, or at least self-conscious. This was at the Judson Hall across from Carnegie Hall, in a kind of arena theater. Later on, in the middle of the piece (all kinds of things were going on: there was even a chimpanzee in it) I turned on a projector that was hidden in the scaffolding on one side of the set and it threw the image onto a screen on the other side of the set, across all the actors, who by that time were directed to lie down on the floor. Around six minutes into the film (which lasts about eleven minutes) I walked over to the screen with another screen, a hoop, and carried the image back to the projectorput it away in a sense. We did this for five evenings, I think.

Fist Fight

is almost twice as long as any film I'd madebecause of John Cage. I'd been going to Cage concerts. Cage didn't cater to the public at all. Whatever his program for the evening was, it went on interminably. He didn't seem to have any theatrical sense of time or timing. I found that very refreshing and thought maybe I could apply it to the film. It was one of the few times I deliberately did something that

Page 39

wasn't an aesthetic reaction to the material I was working with. I made an arbitrary, intellectual decision that the film would be twice as long as I thought it should be. I figured that for the first six minutes people would be resisting the onslaught of imagery, but if I kept on going, they'd give in and relax and begin to look at it the way I wanted them to. I think it's a specious bit of theorizing, but that's how the film got to be so long. I thought I could drive it home by dint of overkill.

I'm uneasy when I see the film now, since most people project it at its full length. Kubelka tried to solve the same dilemma by showing his films over and over. Kubelka's obsession is that people have to know everything about his work. It's a little totalitarian to insist that people look at your work over and over, but that's a matter of style. I'd like the same thing, only I wouldn't want to force you into it.

To get the audience to look at films that are proposing different conventions, you first have to disabuse people of their ordinary conventions. Then you have to introduce them to the new conventions. Only then can they see the film the way the artist expressed it. Filmmakers of our ilk have to wait for the public to get educated to the conventions of this kind of filmmaking, but while we wait, our conventions are usurped and absorbed into mainstream cinema. I think most of the pioneer filmmakers of this kind of filmmaking have been fucked. They were pioneers and didn't get to cash in. Some of them are bitter and disappointed.

On the other hand, I think it's fatuous to set yourself up as a pioneer and point at yourself narcissistically and assume everybody's going to congratulate you. It's a self-serving attention-getting process that doesn't guarantee good art. You just look around, see what nobody else has done, and do it. In itself that's not something to be appreciated.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «A Critical Cinema 2: Interviews with Independent Filmmakers»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «A Critical Cinema 2: Interviews with Independent Filmmakers» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «A Critical Cinema 2: Interviews with Independent Filmmakers» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.