At that age, his moles were disappearing—a mole typically lasts 50 years—and in their place, a couple of “cherry moles,” which look like cherries and the technical name for which is “hemangiomas,” appeared on his chest. His doctor said he thought my dad’s hemangiomas (benign tumors composed of large blood vessels) were beautiful. Easy for him to say; he’s a whippersnapper of 67. My father found the cherry moles as distressing as if he were a teenage girl with an array of pimples on her chin.

At 97, a month before dying, Bertrand Russell said to his wife, “I do so hate to leave this world.”

Bernard de Fontanelle, a French scholar, who died at 100, said, “I feel nothing except a certain difficulty in continuing to exist.”

Aristotle described childhood as hot and moist, youth as hot and dry, and adulthood as cold and dry. He believed aging and death were caused by the body being transformed from one that was hot and moist to one that was cold and dry—a change which he viewed as not only inevitable but desirable.

In As You Like It, Jaques says, “And so from hour to hour, we ripe and ripe, / And then from hour to hour, we rot and rot.” The Sullivan County (NY) Yellow Pages informs its readers that “the process of living means that we are all temporarily able-bodied persons.” The 34-year-old American poet Matthea Harvey writes, “Pity the bathtub its forced embrace of the human form.” Time, to paraphrase Grace Paley, makes a monkey of us all—even my father, fight it fiercely as he does.

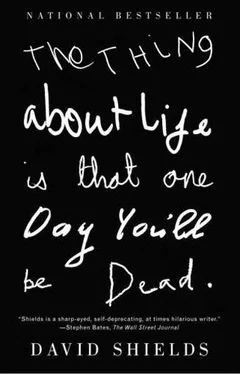

The Thing About Life Is That One Day You’ll Be Dead

John Donne said, in a sermon, “We are all conceived in close prison, and then all our life is but a going out to the place of execution, of death. Nor was there any man seen to sleep in the cart between Newgate and Tyburn—between the prison and the place of execution, does any man sleep? But we sleep all the way; from the womb to the grave we are never thoroughly awake.”

Charles Lamb said, “The young man till thirty never feels practically that he is mortal.”

John Ruskin said, “Am I not in a curiously unnatural state of mind in this way—that at forty-three, instead of being able to settle to my middle-aged life like a middle-aged creature, I have more instincts of youth about me than when I was young, and am miserable because I cannot climb, run, or wrestle, sing, or flirt—as I was when a youngster because I couldn’t sit writing metaphysics all day long. Wrong at both ends of life…”

The eponymous hero of Chekhov’s Uncle Vanya says, “I’m forty-seven now. Up to a year ago I tried deliberately to pull the wool over my eyes so that I shouldn’t see the realities of life, and I thought I was doing the right thing. But now—if you only knew! I lie awake, night after night, in sheer vexation and anger that I let time slip by so stupidly during the years when I could have had all the things from which my age now cuts me off.”

Edward Young wrote, “At thirty man suspects himself a fool; / Knows it at forty, and reforms his plan / At fifty chides his infamous delay, / Pushes his prudent purpose to resolve; / In all the magnanimity of Thought / Resolves, and re-resolves; then dies the same.”

Picasso said, “One starts to get young at the age of sixty, and then it’s too late.”

At 62, Jonathan Swift said, “I never wake without finding life more insignificant than it was the day before.”

Leonardo da Vinci, who died at 67, said, “Here I thought that I was learning how to live, while I have in reality been learning how to die.”

Barry Hannah says, “The calamity is that we get only seventy-five years to know everything and that we knew more by our guts when we were young than we do with all these books and years and children behind us.”

At 78, Lord Reith, the first general director of the BBC, said, “I’ve never really learned how to live, and I’ve discovered too late that life is for living.”

The seventeenth-century moralist Jean de la Bruyère said, “There are but three events in a man’s life: birth, life, and death. He is not conscious of being born, he dies in pain, and he forgets to live.”

Regrets only:

My father came up from the Bay Area to visit for the weekend and my Father’s Day present, six days late, was box seats to a Mariners game. I was new to Seattle and this was the first time I’d been inside the Kingdome which, with its navy blues and fern greens, looked to me like an aquarium for tropical fish. The Kingdome reminded my father of “dinner theater,” and he wanted to know where John Barrymore was. My dad was turning 79 the following month; he wanted—at 80—to quit his part-time job and drive a Winnebago cross-country, then fly to Wimbledon to eat strawberries and cream.

The sixth-place Mariners were playing the last-place Tigers on Barbecue Apron Night. Watching batting practice, we folded and unfolded our plastic Mariners barbecue aprons, which smelled disconcertingly like formaldehyde, and we ran through all the baseball anecdotes he’d told me all my life, only this time—because I pressed him—he told each story without embellishment. He’d always said that he played semi-pro baseball and I had images of him sliding across glass-strewn sandlots to earn food money; it was only guys from another neighborhood occasionally paying him 10 bucks to play on their pickup team and throw his “dinky curve.” He used to say that he was team captain for an Army all-star baseball team that toured overseas, and as a kid I convinced myself that he spent 1943 in Okinawa, hitting fungoes to Ted Williams and Joe DiMaggio. He was only traveling secretary, the most prominent player on the team was a Detroit Tiger named Pat Mullins, and it was fast-pitch softball Stateside.

My father used to look almost exactly like Dodgers coach Leo Durocher (“Nice guys finish last.”). When we were living in Los Angeles, the garbageman supposedly shook my father’s hand and said, “Sorry to hear about your marriage, Mr. Durocher.” Durocher had been recently divorced from the actress Laraine Day; the garbageman was being sympathetic in the male manner—so went the story. And for some reason I always thought my father stood atop the trash in the back of the truck, hefted garbage cans with one hand, and cursed The Fishbowl Which Is Hollywood, whereas in actuality he immediately told my mother about impersonating Leo Durocher, she cautioned him against stringing along the innocent garbage collector, and he chased down the truck to explain and make amends.

Before the game, there was a “Peace Run” around the field—some sort of marathon-for-a-cause which I didn’t quite catch because the PA system sounded like it was being filtered through a car wash—then the umpires strolled onto the Astroturf. This is Seattle, so they weren’t booed even a little, though, which disappointed my father. In 1940, he was the star student at a Florida umpire school run by Bill McGowan, who said my father could become “another Dolly Stark” (i.e., a Jewish umpire), but before reporting to Class D ball my father begged off, citing his poor night vision. He wound up umping Brooklyn College–Seton Hall games and once got whacked over the head with a walking stick when he called someone’s favorite son out at home with two on, two out, the score tied, and the light, I guess, failing. My father’s favorite Bill McGowan story concerned the time McGowan, a former amateur boxer, grew weary of Babe Ruth’s grousing and, during the intermission of a doubleheader, challenged the Babe to a fight. The Babe backed down. The hero of my father’s stories is usually someone else. It’s rarely him.

The Mariners scored three in the first. Keith Moreland looked painfully uncomfortable at third for the Tigers. Ken Griffey Jr. made a nice catch in the fifth. The game was devoid of much interest, though, for either of us (longtime Dodger fans)—as my father said, “like watching a movie when you don’t care what happens to the characters.”

Читать дальше