There are now more people in the United States over 65 than ever before. Only 30 percent of people ages 75 to 84 report disabilities—the lowest percentage ever reported.

Five to 8 percent of people over 65 have dementia; half of those in their 80s have it. One of many dementias and the most common, Alzheimer’s affects 1 in 10 Americans over 65, 1 in 2 people over 85. Alzheimer’s patients are more likely to have had a low-stress (i.e., mentally unstimulating) job. Zero sign, though, as yet of Alzheimer’s in my father: he’s still reading and rereading Robert Caro on Robert Moses, Philip Roth on Newark, Arnold Rampersad on Jackie Robinson, Gar Alperovitz on the decision to drop the atom bomb.

According to Noel Coward, “The pleasures that once were heaven / Look silly at sixty-seven.”

At 68, Edmund Wilson said, “The knowledge that death is not so far away, that my mind and emotions and vitality will soon disappear like a puff of smoke, has the effect of making earthly affairs seem unimportant and human beings more and more ignoble. It is harder to take human life seriously, including one’s own efforts and achievements and passions.”

“Tomorrow I shall be sixty-nine,” William Dean Howells wrote to Mark Twain, “but I do not seem to care. I did not start the affair, and I have not been consulted about it at any step. I was born to be afraid of dying, but not of getting old. Age has many advantages, and if old men were not so ridiculous, I should not mind being one. But they are ridiculous, and they are ugly. The young do not see this so clearly as we do, but some day they will.”

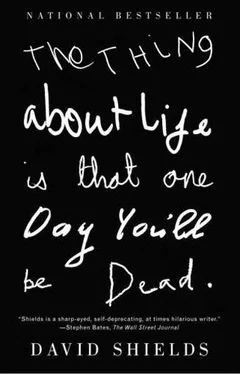

Thomas Pynchon says, “When we speak of ‘seriousness’ in fiction, ultimately we are talking about an attitude toward death—how characters may act in its presence, for example, or how they handle it when it isn’t so immediate. Everybody knows this, but the subject is hardly ever brought up with younger writers, possibly because given to anyone at the apprentice age, such advice is widely felt to be effort wasted.”

Fifteen years ago, on a gorgeous spring day, my father and I jogged down my block. A school bus of middle-school girls rounded the corner. He puffed out his chest, let out his kick, put himself on display. Rather than ooh or aah or whistle or applaud or ignore him, several girls stuck their heads out the windows in the back of the bus and did the cruelest thing possible: they laughed.

“You’re only young,” AC/DC sing on Back in Black, “but you’re gonna die.”

In your late 60s, you eat less. Your metabolic rate decreases slightly. Men lose 3 percent of their skeletal weight per decade (my father now weighs 150); women lose 8 percent. Throughout adult life, men lose about 15 percent of their total mineral density; women, 30 percent. The diameter of your forearm shrinks, as does the diameter of your calves.

The density of your skin’s circulatory systems—veins, capillaries, arterioles—is reduced, which is why old people feel cold sooner. Also, your skin functions less well as a barrier because the skin is thinner—like wearing too light a coat. As you age, your facial skin temperature falls. For older people, a comfortable temperature is 10 to 15 degrees higher than it is for a younger person.

• • •

Each day of your adult life, you lose 30,000 to 50,000 nerves and 100,000 nerve cells. Over time, your heart, lungs, and prostate enlarge. The level of potassium in your body declines. After age 70, your ability to absorb calcium is dramatically reduced.

Tolstoy wrote to his wife, Sonia, who was 16 years younger than he was, “The main thing is that just as the Hindus, when they are getting on toward sixty, retire to the forests, and every religious man wants to dedicate the last years of his life to God and not to jokes, puns, gossip, and tennis [jokes, puns, gossip, and tennis: paging Milton Shildcrout…], so I, who am entering my seventieth year, long with all my heart and soul for this tranquility and solitude.” He died at 82 when he collapsed in a train station, in flight from Sonia, with whom he’d been quarreling.

At age 70, the mass of your corneal lens is three times larger than it was when you were 20, which causes you to be more farsighted; after age 70, you become more nearsighted. The lens becomes thicker and heavier with age, reducing your ability to focus on close-up objects. Your sensitivity to contrast declines, as does your ability to adapt to changes in light. As you get older, the corneal hue takes on a yellow tint, reducing your ability to discriminate among green, blue, and violet. Blues will get darker for you and yellows will get less bright. You’ll see less violet. As painters age, they use less dark blue and violet.

Sir Francis Chichester, after sailing around the world at age 66, said, “If your try fails, what does that matter? All life is a failure in the end. The thing to do is to get sport out of trying.”

Men and women over age 75 suffer ten times the incidence of strokes as do those between 55 and 59.

The professionally world-weary Gore Vidal said, apropos of having to sell his house on a hill in Ravello, Italy, because he was no longer able to climb the steps, “Everything has its time in life, and in a year, I’ll be 80. I’m not sentimental about anything. Life flows by, and you flow with it or you don’t. Move on and move out.”

When you’re very young, your ability to smell is so intense as to be nearly overwhelming, but by the time you’re in your 80s, not only has your ability to smell declined significantly but you yourself no longer even have a distinctive odor. You can stop using deodorants. You’re vanishing.

“I think the old need touching,” says the social historian Ronald Blythe. “They have reached a stage of life when they need kissing, hugging. And nobody touches them except the doctor.” At 82, E. M. Forster said, “I am rather prone to senile lechery just now—want to touch the right person in the right place, in order to shake off bodily loneliness.” The last few years, whenever I hug my father hello or good-bye, he cries and cries, shuddering.

Voltaire wrote to a friend, “I beg you not to say that I am only eighty-two; it is a cruel calumny. Even if it be true, according to an accursed baptismal record, that I was born in November 1694, you must always agree with me that I am in my eighty-third year.” When you’re very old, you want to be thought even older than you actually are: it’s an accomplishment. At 67, my father purchased an annuity that he would have broken even on if he’d died at 76; having outlived the actuarial projections by 21 years so far, he tells everyone he meets how much he’s made on it. He buttonholes strangers and informs them that he’s only 3 years from the century mark.

At 83, Sibelius said, “For the first time I have lately become aware of the fact that the period of our earthly existence is limited. During the whole of my life this idea has never actually come into my mind. It occurred to me very distinctly when I was looking at an old tree there in the garden. When we came it was very small, and I looked at it from above. Now it waves high above my head and seems to say ‘You will soon depart, but I shall stay here for hundreds more years.’”

At 85, Bernard Baruch said, “To me, old age is always fifteen years older than I am.”

At age 90, you’ve lost half of your kidneys’ blood-filtering capacity.

You grow increasingly less likely to develop cancer; the tissues of an old person don’t serve the needs of aggressive, energy-hungry tumors.

By 90, one in three women and one in six men suffer a hip fracture, which often triggers a downward spiral leading to death. Half will be unable to walk again without assistance. My father, on the other hand, walked a mile to and from the library—carrying books in each direction—until he was 95.

Читать дальше