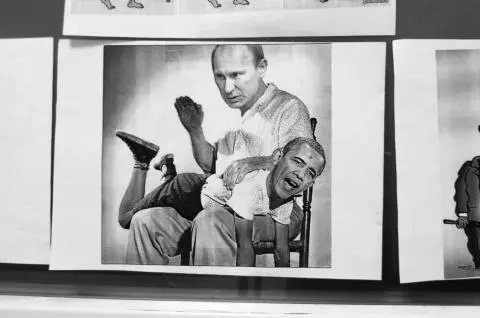

Putin spanks Obama. Picture taped to the wall of the rebel-held regional administration building in Donetsk. April 2014.

As we talked Mihaylova echoed Putin’s famous speech to the Duma in April 2005 saying that the collapse of the USSR was a geopolitical catastrophe. “It is not just Putin who thinks that,” she said, “and many people believe that one of the results of that was an artificial border between Ukraine and Russia.” Both points are debatable. Many borders are artificial and that is exactly why the post-Soviet republics decided not to challenge them. If one border could be legally and militarily contested, and not just relatively minor ones as in the Caucasus, then all could be challenged. Now that they have been—in Crimea formally, and in the east of Ukraine quite possibly, depending on the outcome of the war and whether Russia finally decides to annex these areas too—this is a threat across the post-Soviet space, including of course Russia. It is noteworthy that in his April 2005 speech Putin underlined that one of the most disastrous consequences of the collapse of the USSR was that “for the Russian nation, it became a genuine drama. Tens of millions of our co-citizens and compatriots found themselves outside Russian territory.” And it is precisely this that Putin has begun to correct.

Russians outside Russia, however, was not the topic of the moment. Mihaylova was warming to another theme. Ukrainians should be grateful to Stalin, she declared, because he had fashioned the Ukrainian Soviet republic out of diverse bits of territory and this was now the state they had. Historically this region, known as the Donbass, had belonged to Russia, but Lenin had given it to Soviet Ukraine in the aftermath of the Russian Revolution and civil war when the region, or rather communists here, had declared this to be the Donetsk–Krivoy Rog Soviet Republic. It was a short-lived affair, extinguished as the Red Army defeated its enemies, including the also short-lived German-supported Ukrainian state, which the Donetsk–Krivoy Rog Republic had resisted. Now, she said, it was a ridiculous irony that Ukrainians were destroying statues of Lenin when they should be grateful to him.

Although in 2015 the DNR declared itself to be the legal successor of the 1918 republic, few people there actually knew much about it, as it was a taboo topic in Soviet times. This was of course because it had fought against incorporation into Ukraine. Today’s black, blue and red DNR flag is based on its flag of 1918, though then it was soon dropped for a red banner. What is more revealing for us though are Mihaylova’s views on Stalin which, shocking though they may be to us in the West, are widespread in Russia and among many Russians. I was baffled, I said, that she could expect Ukrainians to be grateful to Stalin, when he was responsible for the famine of 1932–33 in which some 3.3 million are estimated to have died. (The figure is that of Timothy Snyder, the Yale historian of the region and the period, but many put it far higher.) “The legend of the Holodomor ,” she said, using the name given to it by Ukrainians and which means “hunger-extermination,” was created in Canada by fascist Ukrainian exiles. Yes, some had died, but to argue that Stalin had deployed it as a weapon against Ukrainians was a “fairy tale.” Russians had died too. There is a legitimate debate about this issue and to what extent Stalin used the famine to eliminate and break the will of the Ukrainian peasantry—because they were Ukrainian—but the tone of the conversation suggested something else. Stalin was a great man and the death of millions was a minor detail which should not sully the big picture. So, when it came to the Gulag, to which millions of Ukrainians were sent, not to mention Russians and other Soviet citizens of course, she argued that “that story is like Snow White, or…” and at this point Ludmila, who was translating for me, stumbled, looking something up on her iPhone translator. “Thumbelina? Do you know what that is?” Yes, said Mihaylova, there was an organization and there were prisons, but it was nothing more serious than this. Stalin took this country, one in which people used “wooden plows and left it with nuclear weapons and he was no more evil or tough than Roosevelt or Churchill at the time.” Stalin has a “bad image in the West” but he was “good for us.”

Listening in was Viktor Priss, a twenty-eight-year-old IT systems administrator, who worked in the office. In a previous job he had worked for the confectionary company of Petro Poroshenko, the man who would a few weeks later be elected as Ukraine’s next president. Viktor is the type of man much in demand by Western IT companies, either to work for them in Ukraine or abroad. He was only a small child when the USSR expired. He did not think that the Gulag was a fairy tale. Stalin’s problem was that “it was very difficult to hold the country together with such an ideology and some people disagreed, so it was necessary to re-educate them.” Stalin was a product of his time and “time creates its leaders.” In that sense, he argued, he had been a product of the will of the people to create a dictator. The Soviets created a signal that “we were in danger,” and as a result had sent a message, which was interpreted by the people as meaning “we are ready to help you” and hence Stalin “was a dictator by the will of the people.” Viktor was not sure if the same applied to Hitler given that he was after all elected, unlike Stalin. As for Putin, while there were no social conditions for him to become a new Stalin, he could certainly become the type of leader ready to respond to the will of the people. And presumably, for those who think like Viktor, that is what he is already doing.

For a foreigner it is hard to fathom such logic and quasi-mystical thinking about leaders and especially Stalin, responsible for so many millions of dead. But, in this context, what is important to understand is that, if people think that Stalin made the world tremble and that everything has gone to hell in a handcart since the end of the Soviet Union, then, with such a black-and-white view of history, for them restoring him to greatness makes sense. If this is what you believe, then Stalin cynically doing business with the devil, or in this case Hitler, by drawing a line from the Baltic to the Black Sea and destroying other countries, as was done in the Molotov-Ribbentrop pact of 1939, is fine. And what does Putin think of this? In 2009 he said that the pact had been “immoral,” but in 2014 he revised his opinion and claimed it had been to avoid fighting, and what was wrong with that?

When, to the shock of the world, Hitler and Stalin agreed to carve up eastern Europe, Stalin sparked off the Second World War. In the period from 1939 to 1941, the Soviet Union was allied to Nazi Germany and supplied it with the raw materials it used to make war on the Western allies. After Hitler attacked the Soviet Union everything changed of course, but officially the Soviet account could only say that the war had begun in 1941. Understanding this is central to understanding Ukraine today. The story of the great sacrifices of the Soviet people in the Second World War and the struggle against Nazism has been detached from the years 1939 to 1941, which saw the conquest and annexation of Lithuania, Estonia, Latvia and eastern Poland; from Romania, Bessarabia and northern Bukovina were annexed. When the Red Army met the Nazis in Poland, there were cordial meetings of military commanders and soldiers and an agreement to crush any Polish resistance. The NKVD, who were interior ministry security men and troops, and part of which was the progenitor of the KGB—now the FSB in Russia and the SBU in Ukraine—went into action. Tens of thousands were deported from the conquered Baltic states, Bessarabia and northern Bukovina, and hundreds of thousands of Poles were sent to the Gulag. Thousands of Polish officers were murdered, most infamously in the Katyn Massacre of 1940.

Читать дальше