Next Year in Donetsk

When wars begin there is a strange period when ordinary, pre-war life continues before the new rhythm of wartime begins. It is also the period of disbelief and delusion, euphoria or shock. At the beginning of the First World War millions across Europe enthusiastically cheered their men marching off to fight, having no inkling of the catastrophes that lay before them. In 1939, in the West, after war was declared and before the Germans began their advance, we had the “phoney war.” In our times, in Bosnia in 1991, as war raged in neighboring Croatia, many assumed that it would not spread because, as everyone knew and said just how bad it would be, no one believed that anyone would be so stupid as to actually start it. When it did start in 1992, the first months were chaotic. No one knew who was firing at whom and from where. Then things settled down: frontlines became clear and for three years people got killed, cities and towns were besieged and hundreds of thousands fled or were ethnically cleansed, but the front did not move much until the very end. All of this was in my mind as the war began in Ukraine. All too often I saw similarities with the Balkan wars, all of which I had reported on. A period of the surreal preceded the new reality. You could see this both in Kiev and Donetsk where, even if people talked of war, it was clear that they did not believe it was really coming.

In early April 2014, in the center of Kiev, on the Maidan and Khreshchatyk, the city’s central boulevard, and on the road leading up to Parliament you could see the remnants of revolution. There were makeshift shrines and candles for the 130 who died during the revolution, many of whom had been cut down by snipers. A year later no one had been brought to justice for this crime, which was widely assumed to have been ordered by Yanukovych or someone close to him. The failure to find the guilty, bad enough in itself, nourished conspiracy theories, namely that the pro-Maidan protesters had killed their own people in order to blame Yanukovych and hasten his downfall. There was no memorial for the eighteen Berkut riot and other policemen, many who came from units brought in from Crimea and the east, who had died fighting the protesters—deaths which were not forgotten or forgiven in the places they had come from, a fact which did much to engender bitterness.

Around the Maidan there was a tent encampment. Perhaps a thousand people remained here. They had collection boxes for their different groups. People dressed as bears, Mickey Mouse, or zebras ambled about hoping that you would want to pay to have your photo taken with them. There was a large catapult which looked as if it had been taken from the set of a film about the siege of Troy. The stage from where people had spoken remained, though now it sported a large ad for the newly formed military National Guard. It also had a large crucifix propped up in front of it. There were pictures of Stepan Bandera, the controversial and divisive Ukrainian nationalist leader of the Second World War, and Vladimir Putin, Russia’s president, who had been given a Hitler mustache and hairstyle. Those who remained here said they wanted to stay until the presidential elections on May 25. Many just seemed lost. They included men and women from outside Kiev to whom the revolution had given a sense of purpose for the first time in their lives; now they were staving off a return to humdrum lives back home. Between the Maidan and Parliament, all sorts of militias in different uniforms marched up and down, but to what purpose was not clear. Outside Parliament I asked Andreii Irodenko what he and his men were doing and might they not serve Ukraine better in the east, and he replied: “If we left this spot, provocations would start here.” He said that provocateurs could be agents of the FSB, Russia’s secret service, and other supporters of Russia.

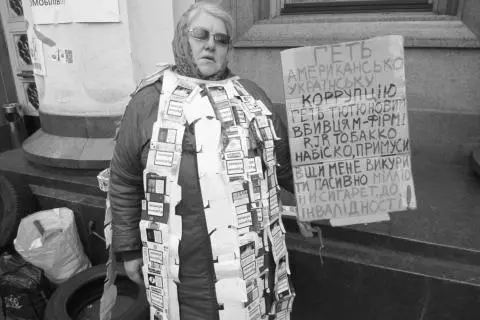

While the threat of losing complete control of the east loomed, all sorts of people and groups demonstrated outside the building of the Verkhovna Rada, Ukraine’s parliament. Some were demanding a lustration of judges and some were protesting about legislation concerning duties on imported cars. At the door of Parliament, Myroslava Krupa, who had made herself a cloak of cigarette boxes, was protesting because she had not received compensation for damage to her health caused, she said, by poor conditions at an American tobacco company she had worked for in Lviv. Strange groups roamed around and roads were blocked. Suddenly a black car driven by a glamorous woman frustrated at not being able to get to where she wanted, veered off down a path in the park only to be stopped and surrounded by an angry crowd. One man was dressed as the Grim Reaper, with a black cloak, mask and scythe on which he had written: “Putin, I am coming for you.” No one in Kiev quite seemed to grasp what was happening in the east, which was surprising since Crimea had already been lost more than a month before.

Myroslava Krupa in a cigarette packet cloak protesting at the Verkhovna Rada. Kiev, April 2014.

Many were alarmed and disappointed. They had braved the bullets and the cold for a root and branch change for Ukraine, but now the leading candidates for president were Yulia Tymoshenko, the oligarch and former prime minister who had been jailed by Yanukovych, and Petro Poroshenko, a billionaire who had earlier been a minister under Yanukovych.

Middle-class Natalyia Yaroshevych, aged forty-eight, who sells cosmetics for the American company Amway, said she had liked what she had seen at the beginning on the Maidan, but later felt that “political games were being played” there by Russia, the EU and the U.S. As we sat in a café at Ocean Plaza, a Kiev shopping mall featuring a giant fish tank with sharks, the French supermarket Auchan, Gap, Marks & Spencer, and many of the other big Western chain stores, she said she was “anxious but not fearful” of war but what concerned her and many of her friends even more was the cost of living. Her husband, an engineer, had his own small company installing and maintaining industrial gas meters. Orders had plummeted because of the crisis and he was worried about the family’s income because like many, not only in Ukraine but other parts of the former communist world, they had taken out a mortgage denominated in a foreign currency. Few understood the implications of these when they borrowed. When the Yaroshevych family took out their mortgage, just before the financial crisis of 2008, the exchange rate for $1 stood at 5.5 hryvnia. Before the Maidan revolution started it was 8 hryvnia. Now it was 11 hryvnia. For ordinary people, whatever was happening in the east, bills still had to be paid and the risk of losing your home to the bank was a more immediate and existential threat to them than the idea of losing Donetsk in a war which might or might not come to Kiev. (A year later, $1 was 22 hryvnia, but the Yaroshevych family had been able to solve their problem. Natalyia’s husband sold his office and paid off the home mortgage.)

On April 6, 2014, armed men seized the regional administration building in Donetsk. Then they began to fortify it with sandbags and tires and a few thousand came to show their support. For many outside the building there was a sort of carnival atmosphere. Roadblocks manned by armed men went up. At one, near the town of Sloviansk, which would briefly be a rebel stronghold, a man said that what was happening here was going to be “just like Crimea.” In other words, he thought that without a shot being fired, Russia would swiftly annex the Donbass, the name of this eastern region. Nearby, at another checkpoint manned by rebels, who mostly seemed to be locals, they lined up rows of Molotov cocktails a stone’s throw from a roadside shop selling serried ranks of garden gnomes.

Читать дальше