All this voting was obviously too much for the old guard and it was clear to them that it was a factor in the dissolution of the state. But it was their own rearguard action which was to deliver the final blow to the USSR, when they launched a coup against Gorbachev in August 1991. Leonid Kravchuk, the canny Ukrainian leader, was noncommittal until it was clear that the coup would be defeated and then came out against it. Then the Verkhovna Rada voted in favor of independence by 346 to 1.

On December 1 Ukrainians were voting again. They were asked if they supported the act of independence. This time 92.26 percent were in favor. Not a single region voted against, including traditionally pro-Russian Crimea, which voted 54 percent in favor. The next two regions with the lowest support were Donetsk and Lugansk, which still voted “yes” by 83.9 percent and 83.3 percent respectively. For many nothing was really clear. Many believed that independence would mean a new start, but at the same time everyone in the Soviet Union would somehow stay together under the umbrella of the new Commonwealth of Independent States—no one really knew, and indeed this is an important point. None of these referendums, which are often taken as such important benchmarks of popular will, was anything that anyone in the West would ever remotely accept for their own country. In no case were there years of erudite discussion, in the media above all, of the cases “for” and “against” as there were in Scotland in 2014 or Quebec in 1995, for example.

In Mariupol, I talked about the recent Donetsk referendum with Liubov Ivaschenko, a doctor aged sixty-one, and asked her what she had thought at the time of the 1991 independence referendum. “I was very hopeful,” she said, “but at the same time I felt nostalgia for Soviet times and for our capital Moscow.” This seemed to encapsulate something.

For many, those heady days of hope were to evaporate very quickly with the complete collapse of the economy. In Donetsk, Crimea and some other places small groups agitated for a restoration of ties with Moscow and even a restoration of the USSR. So, in 1994, concurrent with the general election a new “consultative” referendum was held in Donetsk and Lugansk. Consultative meant that it could be considered more of a glorified opinion poll rather than something with a legal status. People were asked if they wanted Russian to be a state language with equal status to Ukrainian, the language of the local administration, and whether they wanted a federal Ukraine. As usual the response was a resounding “yes.” But then nothing happened. Small groups agitated, politicians from the east such as Yanukovych came to power, lost it and regained it, and tiny groups grumbled, moaned and organized, some talking of restoring something called Novorossiya or the New Russia of Catherine the Great and some of the Donetsk Republic of 1918. Hardly anyone in the Donbass noticed these people or what they were doing on the far fringes of political life.

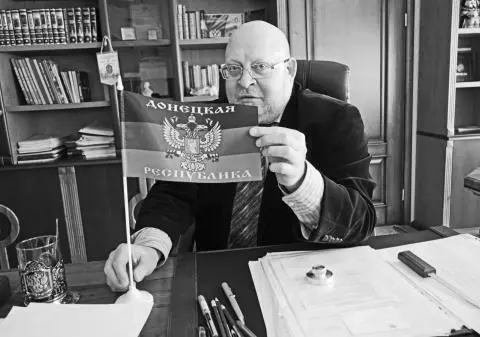

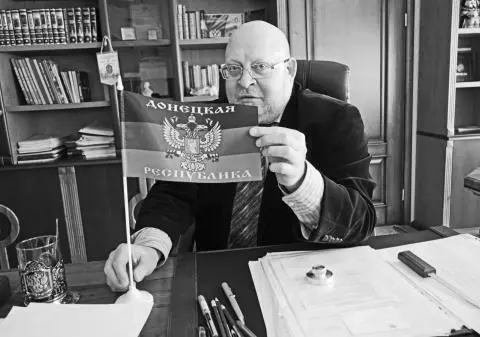

Sergei Baryshnikov, with a Donetsk People’s Republic flag, in his office in Donetsk University. March 2015.

When I first met Sergei Baryshnikov he was hurrying off to give aid to soldiers. A political scientist and a member of the DNR’s then unelected parliament, at the beginning of September 2014 he was a man whose time had arrived. A few weeks later the DNR authorities appointed him to take over the university. He had worked here for some twenty years but resigned in 2012, although there were allegations that he had departed under a cloud and amid rumors of bribe-taking. As the war began he was part of the small group of pro-Russians who played a role in organizing the rebellion in Donetsk and calling for Russian troops to intervene. As he left to hand out his aid, I asked him if there were any here and he replied enthusiastically, “Yes, thousands!” Then, perhaps remembering that the official Russian position was that there are no regular troops in what he was calling “the former Ukraine,” he noted that all of them were “volunteers.”

Officially the university has gone into exile in Vinnitsa in central Ukraine. Many academics and students have left and some are following courses online. But for those who remain, who either did not want to leave, could not leave or are academics not purged by Baryshnikov, he is now the boss. He is important not only because of that but because he is one of the leading ideologists of Novorossiya and the DNR. On his desk he has its flag and on the wall a portrait of Vladimir Putin. He is “our president,” he said, “de facto, our leader.”

I wanted to discuss the origins of the DNR. In the early 1990s a welter of political organizations sprang up in the east, all trying to represent the Russian-speaking population of the Donbass and Ukraine. Most were small and now forgotten. But the one Baryshnikov mentioned was set up in 1989 and was called the Inter-Movement of Donbass. It aimed to preserve the USSR and was related to similar movements in the Baltic republics. One of its leaders was Dimitry Kornilov, a man who was fascinated by, and collected information about, the 1918 Donetsk–Krivoy Rog Republic and, according to a declaration of the DNR parliament in 2015, was the first to resurrect its flag in 1991.

At the time, said Baryshnikov, he was not so involved politically. He had just gotten married, just had a son and was preparing his doctorate. But he was against Gorbachev, because he said it was clear he was leading the Soviet Union to destruction. The Inter-Movement idea was to “save a multinational sovereign state and stand against nationalistic ideas,” in this case the nationalistic ideas being Ukrainian of course. Baryshnikov supported the coup against Gorbachev in August 1991. The problem with Donbass, though, was that unfortunately its people proved to be “apolitical, passive and apathetic.” People like him who wanted to keep the USSR together and who might be prepared to do something about it were few and far between. Baryshnikov does not believe, however, that the numbers recorded of those who voted for independence in December 1991 are real.

In the ensuing few years he was involved with various organizations which militated for Russian language rights. When he was asked to teach in Ukrainian he refused. As to Yanukovych’s later Party of Regions, which, when in power, did pass language laws aiming to settle the issue of when Russian could and could not be used officially, he says the party was really just a disappointment. In 2012 Baryshnikov began to cooperate with a political activist called Andrei Purgin, who was one of the founders in 2005 of a tiny group called Donetsk Republic. It wanted to re-create the short-lived state, but, he said, they were only a handful of people, some of whom, like Purgin, are important today and some of whom are forgotten. The idea, he explained, was to create a federal state and then to separate from Ukraine. “I was for joining Russia,” Baryshnikov said. “I had always been against Ukraine, politically and ideologically,” though he stopped here to say that what he did like about Ukraine was its food and its women. Now he was warming to his theme. Donbass should be part of Russia, he argued, because historically it had been part of Russia. In fact, now the idea was to re-create a great and single Russia from the Far East to the Baltic states, which would have to become part of it. All of Ukraine should become part of this Russia except perhaps for Lviv and Galicia in the west, which had not been part of the Russian empire before the First World War. “Ukraine should not exist.” The creation of the DNR, he explained, was just the “first stage” that people like him had a “historical mission” to complete.

Читать дальше