As to the question of where money was going and who was subsidizing whom in Ukraine, the answers begin to become clear. Ukraine has twenty-seven regions. Before the war Kiev was the richest, Donetsk was the fifth richest. Seven regions of Ukraine contributed more to the central budget than they gained. Crimea and Lugansk were net gainers. But within Donetsk oblast some areas were much better off than others, so the picture was complicated not least because much of the mining industry was subsidized by the state, i.e., by the taxes of all Ukrainians. Nevertheless one can see how, when the time came, there was dry tinder in Donbass. Many here had been part of the Soviet working-class elite, that is to say, well-paid and well-regarded miners and industrial workers. The end of the Soviet Union stripped them of status, and in many cases jobs and comparatively their standards of living, including in the provision of health care, declined. At the same time individuals such as Akhmetov came to own the most profitable assets of the region and, while local politicians such as Yanukovych could boost local pride and help the employment of those close to his party, in reality and despite monikers such as “pro-Russian” he and they were not. They were pro themselves.

Most of the issues that afflicted Donetsk and Donbass were not unique to them, but the low level of identification with Ukraine, the fact that the most pro-Ukrainian part of the population was the comparatively small but educated middle class, who mostly fled as the war began, meant that there remained plenty of angry people here ready to believe that this was the moment to take action to better their lives when the flags of the Donetsk and Lugansk People’s Republics were raised. If they had known that supporting them would spark war and the now probable economic death of their region, history would have been very different.

In terms of population the war has been a catastrophe, especially bearing in mind that the region had lost almost a third of its inhabitants well before the conflict began. By spring 2015, from the wider Donbass region afflicted by the conflict, some 45 percent were believed to have fled, either west into Ukrainian-controlled territory or to Russia. The educated middle class tended to flee west and, as the fighting dragged on and people began new lives elsewhere, it was clear that fewer and fewer would ever return, whatever peace eventually looked like.

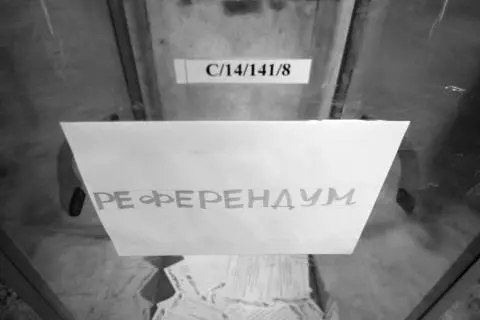

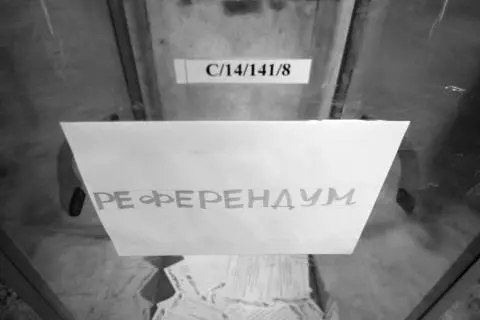

Ballot box in Sloviansk for the Donetsk People’s Republic referendum, May 11, 2014. The sign says “Referendum.”

On May 11, 2014, the rebel authorities held a referendum in which people were asked: “Do you support the act of state self-rule of the Donetsk People’s Republic?” Since pro-Ukrainians boycotted it or had fled and anyway the referendum was a chaotic affair, it is quite possible that 89.7 percent of those who voted—and no one knows for sure how many did—actually said “yes.” In the DNR the rebels claimed a 74.87 percent voter turnout, but the Ukrainian Ministry of Interior claimed the figure was 32 percent. Meanwhile, the Ukrainian presidential election was due to be held on May 25 and posters for a couple of candidates had gone up in Donetsk, though the DNR authorities would prevent this from happening in the territory they controlled and it was far too dangerous for anyone to campaign here.

A week before the Ukrainian poll I went to a cigarette kiosk in Donetsk and asked the woman inside how business was. As the war was beginning, all those I had previously asked unsurprisingly said business was terrible. Well, she said, as everyone was stressed, they were smoking more and so it was pretty good in fact. But she added angrily, “I am so tired… I just want peace and quiet.” While we talked a stream of people came and went buying cigarettes. Everyone agreed with her. When I asked her about the presidential elections she said that she supported Ukrainian unity but not the current government in Kiev, “which took power by force.” One of the election posters was for the new leader of Yanukovych’s old party, which used to have overwhelming support in Donetsk. About the two candidates whose posters could be seen in the city, one woman, picking up her cigarettes, snapped that they were “werewolves.” I asked a disheveled old lady what she thought of Denis Pushilin, one of the main separatist leaders, and she said shrilly: “What did he do? My pension has not increased!”

Two girls came by and a middle-aged female Jehovah’s Witness who opined that everything that was happening was God’s will. The girls, who were both seventeen, said their parents wanted to vote but did not know whom for. The Jehovah’s Witness gave them some leaflets, the only ones being handed out in this election in the east, and wandered off. Then one of the girls said that her parents had voted in Donetsk’s referendum. Whatever happened, said Nastia, they just wanted there to be “no war.” The woman in the kiosk was getting hot and bothered. She excused herself and slammed shut the tiny window to preserve the cool air from her air-conditioning inside.

I could have interviewed as many analysts and political scientists as I wanted but would never have gotten as concise a snapshot of what people in the east were thinking as that. Not only did they not feel represented by any politician but, when it came to what the DNR was about, there was utter confusion. Some had thought they were voting for independence in its referendum, but others for autonomy within Ukraine and hence they could still vote for the country’s president. The reason it was so unclear in the DNR was because the term “state self-rule” could be interpreted in different ways, and presumably this was done intentionally to lure voters who were against independence but in favor of a federal structure for Ukraine, which had been discussed over the years. (The Lugansk question was much clearer and asked about “state independence.”)

What was also clear, if you look at the past, is that people here, as in the rest of Ukraine, are always “for” something, because they want their future to be better than their past. In recent history too, supporters of one side or another always point to a referendum in which people have voted for something they approved of, and then ignore the ones where they have voted for something they do not want.

On March 17, 1991, for example, Mikhail Gorbachev, the last Soviet leader, held a referendum in which people were asked whether they wanted to preserve the USSR “as a renewed federation of equal sovereign republics.” The Baltic states, Georgia, Armenia and Moldova did not take part, and a boycott was called for in western Ukraine. Still, 71.48 percent of those who voted in Ukraine did so for a renewed USSR and, although this was the lowest “yes” figure in the Soviet Union among all those who voted, it was still overwhelming. However, in Ukraine, people were asked some separate questions as well. Did they want Ukraine to be “part of a Union of Soviet Sovereign States on the basis of the Declaration of State Sovereignty of Ukraine”? The meaning of this was extremely opaque, at least to ordinary people. In fact this had been adopted in the Verkhovna Rada the year before and amounted to a virtual declaration of independence. It established that Ukrainian law, not Soviet law, was supreme, that the republic had the right to its own army and so on. The answer to that was “yes” too with 81.7 percent, and it meant that a majority had been voting “yes” simultaneously to ideas which in reality could never be reconciled. At the same time people in the west, in Lviv, Ternopil and Ivano-Frankivsk, were asked if they wanted complete independence, to which the answer was again “yes” by 88.3 percent.

Читать дальше