By now Florence and I had most of six months together. I don’t know that there was one moment when I could have said that we were in love. It was just a slow process in which we began to care for each other. We talked about me going into the war. We knew that it was going to happen sooner or later. We didn’t know when.

Toward the end of September they took our dress uniforms, our greens and hats and shoes. We went on liberty wearing our khakis and combat boots. We called them “boondockers.” Florence hadn’t even been expecting me. I looked all over town for her and finally found her with a bunch of her girlfriends in St. Kilda Park, where we had sat and talked so often.

She knew the minute she saw me.

We just hung on to each other. I kept saying, “I’ll be all right. I’ll be all right.”

I would have loved to have married her right then. But I had sense enough to know what was ahead of me. I didn’t have a clue how long it would last. I knew I couldn’t even think about marrying her and going off and getting killed and leaving her a widow.

“I’ll be all right,” I said. “I’ll come back for you when it’s over.”

But I was wrong.

The Sunday morning after Florence and I said our good-byes, they rousted us out of bed at six and told us to get our gear together. The First and Second battalions had already shipped out by the end of August. Shortly afterward the Seventh Marines had moved to the docks. We knew we were next.

After breakfast we were trucked down to Port Melbourne. We stood around all morning before finally climbing the ramp to the B. F. Shaw , a Liberty Ship.

Then we waited some more.

All that day and into the night we stood along the rails and watched the Shaw take on cargo. Little by little the mountains of crates piled all over the dock, the rows of trucks and jeeps, the artillery and deflated rafts and stacks of stretchers were lifted and lowered into the hold. I didn’t know a ship could carry so much. They had loading down to a science. The least important stuff went in first, then the more important, and finally whatever would be needed right away, like ammunition and drums of fuel. Last on, first off.

That ship sure wasn’t designed to carry troops. We were stuffed into the cargo hold with our gear. We’d sleep in hammocks stacked four and five high and slung between riveted bulkheads and columns. Make-do plumbing facilities were up on the open deck. The chow lines were slow and stretched for yards.

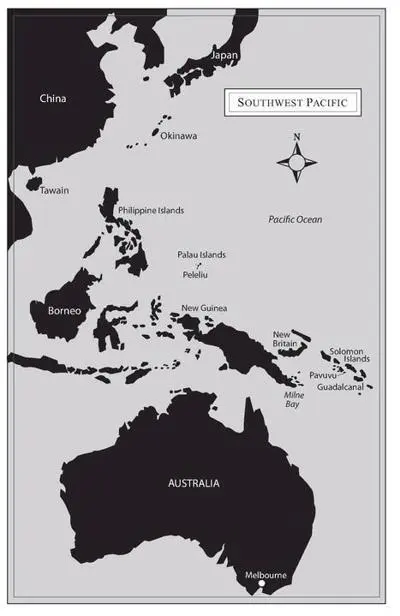

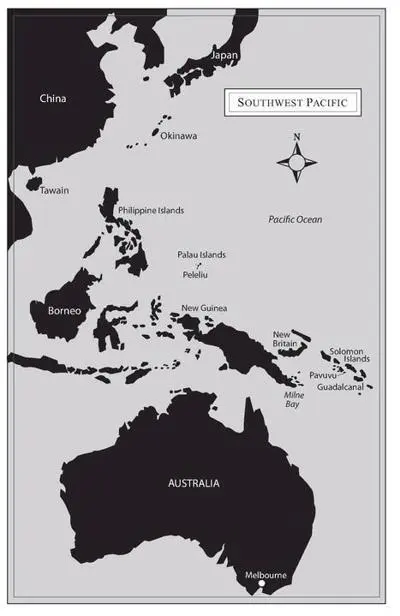

We steamed out of Port Phillip Bay into the ocean the next morning, September 27, then swung around to the north. We had only a general idea where we were headed—to some island someplace. To the war.

We sailed on for a little over a week without incident before pulling in one afternoon at Goodenough Island off the eastern coast of New Guinea. The Australians had cleaned the Japs out the year before, and the First Battalion had already set up an advance camp. We were able to disembark and walk around for a couple hours and get our land legs back. After the gentle, rolling country around Melbourne, Goodenough was a change in scenery and a glimpse of things to come. There was a coastal strip of jungle, then a steep, rugged slope leading up to a sharp volcanic peak. That night we were back aboard ship when a Jap plane came over, low. You couldn’t see him but you could hear him. He dropped a bomb without hitting anything and flew off. But he let us know we were in the war zone.

The next morning we pulled out and three days later, on October 11, we landed at Milne Bay, New Guinea. That would be our home for almost three months. The letters Florence had been writing in Melbourne—the first of hundreds—finally caught up with me. And I wrote my first letters to her.

We found a camp scraped out of the jungle. Rows of tents were set up on either side of a sort of road bulldozed through the mud. The rains came and went, and came and went again. The tents were wet, the ground was wet, our clothes were wet. When we went to lie down, our cots would sink into the muck so that we soon found ourselves sleeping on the ground with only a layer of canvas beneath us. Mornings we stood in formation, ankle-deep in the muddy “street.” Between rains we dried out a little. They scattered some crushed rock around, and that helped a bit.

Mud or not, we still observed the old Marine tradition of cleanliness. Company headquarters was down at the end of the street, and right behind that was a little branch creek. It became our laundry. We’d take a bar of Marine soap and a scrub brush and go down there and find a rock, maybe about a foot wide and not too jagged. We’d lay out our clothes one by one—dungarees, shirt, underwear—soap them up, scrub them with the brush, turn them over and do the same thing. Then we’d rinse them in the running creek and lay them out to dry. If it was sunny, it didn’t take too long. If it wasn’t, we wore them wet.

We were never idle. We were learning the new art of jungle warfare, at it every day with mock combat or with marches, rifle range, pistol range.

In November, Third Battalion got a new commander, and we met him in a strange way. Lieutenant Colonel Austin Shofner had just come up from Australia, where he had been personally decorated by General Douglas MacArthur with the Distinguished Service Cross. In 1942 when he was a captain, Shofner was captured on Corregidor Island and survived the Bataan Death March. After almost a year in a prison camp, he and a dozen others—American Marines, soldiers, and sailors and Filipino soldiers—escaped into the jungle, where they joined local guerrillas to fight the Japs.

We were down in a creek bed shooting our .45s when someone came thrashing out of the underbrush and the vines. It was Colonel Shofner. He asked what we were doing, then told one of the guys, “Set me up a target.”

We did so. He unholstered his .45 and shot one, two, three, four, five times, leaving a perfect V pattern over the bull’s-eye. Then he stuck his pistol back into his holster and walked back into the jungle without a word. I think you could have taken a ruler and not a shot would have been out of line. I never will forget that.

We went on pulling maneuver after maneuver, but we hadn’t practiced landings with the LSTs and LSMs—Landing Ships, Medium—which for some reason were not yet available. Finally one afternoon late in December we boarded DUKWs and started across the bay.

A DUKW—Ducks, we called them—is not much more than a low-sided amphibious truck, about thirty feet long and a little over eight feet wide. It could carry about twenty troops and was pretty smooth and speedy on land but slow and rough-riding in the water. The only time I ever got seasick was in a DUKW, and that day I was not the only one.

Just as the mortar section was getting ready to board our DUKW for an amphibious exercise, the wind and rain came up. That was nothing new to us. By the time we got out into the bay a gray curtain dropped over us. We couldn’t see thirty yards, much less the other DUKWs. Our coxman lost his bearing, and then he lost his breakfast. I wasn’t feeling so good myself. A wave of seasickness swept over everybody. The diesel exhaust blowing in our faces only made it worse. Pretty soon we all had our heads over the side. I think Jim Burke and P. A. Wilson were the only men in that DUKW who didn’t get sick.

In the middle of everything we got hung up on a reef. We sat in the water going up and coming down, up and down, banging on that reef. I thought, It’s going to knock a hole in the bottom of this thing. We’re in trouble out here.

Читать дальше