After a period of leave, I returned to Odiham for some routine flying. It was all about gaining more experience on as many different mission profiles as possible. Then, on June 20th 2005, after a big work up where I practised all the skills that are required of a Chinook captain, I was declared combat ready. It was all about being able to demonstrate captaincy, satisfy the boss that I could take the aircraft on a shitty night, fly across the UK, do the job and come back safely.

Of course, the real pleasure for me was my wings. They were properly sown in now and that was it; they couldn’t take them away from me. Not now. Finally, in June 2005 – almost five years after starting on the journey – I could at last call myself a pilot in the Royal Air Force. I was in!

We’d been tasked to return to Iraq again shortly after I was declared combat ready. In the event though, we were stood down to allow the Merlins to take over in theatre. Shortly afterwards we got the news that we had been earmarked to go to Afghanistan in April 2006, so everything that followed was about us preparing for that.

Some of the guys on the Squadron had been to Afghanistan in the immediate aftermath of 9/11 as part of the operation to oust the Taliban from power, but the landscape was significantly different then. Sangin, Musa Qala, Kajaki – they were meaningless names to us in 2005. There was no back story, no history or association with any particular place. Camp Bastion didn’t exist. Also, there’d been just a single British soldier killed in combat operations. Our worries weren’t so much focused on the enemy, but on flying the aircraft in an environment in which its performance was a complete unknown.

One of my best experiences of flying came when I did a short detachment to the Falkland Islands in November and December 2005. I was flying with Aaron Stewart, who’d become a good friend while I was on 18 Squadron. He earned himself the sobriquet of ‘Tourette’s’ due to his incredible ability to swear prolifically whenever he gets angry. His vocabulary of swear-words is absolutely extraordinary and he delivers them like a Minigun on a high rate of fire! The two of us did some really good flying in some incredibly testing weather, which took both us and the aircraft to the absolute limits of performance. You really only ever see weather like that in the Falkland Islands.

On one particular sortie, we were supposed to be picking up a JCB as an underslung load and putting it on HMCS Brandon , a Canadian Navy ship. We thought it was going to be one of those mini JCBs but it turned out to be the full monty, which weighed about eight tonnes. When we finally got it hooked up and I pulled pitch to lift, we had just a 3% margin in power – right at the limit of the Chinook’s capabilities.

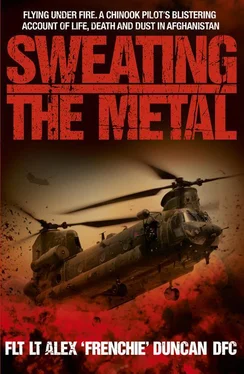

Still, at least we couldn’t see the effect that the load had on our cab, which isn’t the case when you’re flying in a two-ship formation and you’re both carrying massive underslung loads. You can actually see the other cab ‘bow’ in the middle as the load exerts downforce on the airframe. It’s stressed to such a degree that small waves ripple across the metal skin, in much the same way they’d move across the skin on your arms if you were lifting heavy weights. The cabs are worked so hard they’re literally ‘sweating the metal’.

It’s funny how your mind adapts, almost without you noticing. The first time I flew a Chinook I was amazed at its power, but everything has a limit. Once the engines exceed maximum power or temperature, they’ll either blow up or the NR will drop, as they won’t be able to provide the energy required to maintain it at 100%. If that happens, the cab will drop like a stone.

This time, all I had to do was finesse the aircraft over the deck of the ship and gently place the JCB on the deck. Easy, right?

Well, as easy at it can be when you’re hovering a 99ft long helicopter with only 3% torque in hand, an eight-tonne JCB acting as a pendulum under the aircraft, and two rotor discs spinning at 225 revs per minute just 5ft away from the ship’s crane. It would have been all but impossible on any other day in the Falkland Islands (where, even in summer, the wind can exceed fifty knots) but on this particular day it was unusually benign – no more than three or four knots. I learned a lot about flying on that mission that was to prove invaluable in Afghanistan.

Given the Falkland Islands’ isolation and its uncontrolled airspace, you can do things there that just aren’t possible anywhere else in the world. All incoming and outgoing commercial airline flights are intercepted and escorted by two RAF Typhoon fighter jets. The residents of Port Stanley positively welcome low flying (they phone the base and complain if the jets don’t scream overhead at max chat at least twice a week); and at least twice a month the Argentine Navy sails inside the exclusion zone to see just how awake the Typhoon crews are, which heralds a scramble to intercept and chase them away. It’s like a playground for the UK military, but it’s hugely beneficial from an operational readiness perspective.

We used to do something called the ‘Tiger Run’. We would call the RAF Regiment over the radio and say, ‘Tiger Run – game on,’ and they would then turn on the radar for their Rapier anti-aircraft missile system. The object of the game would be to fly the aircraft as low and fast as possible to see how close we could get to the airfield before they managed to get missile lock on us. To beat our personal score meant flying through some of the gullies that ran in from the west straight into the airfield. The flying was intense and took a lot of focus, but it was to prove hugely beneficial when we got to Afghanistan.

In January 2006 we were briefed that we’d be deploying to Afghanistan as a component of 16 Air Assault Brigade and flying in support of ops by 3 Para Battlegroup, under Lieutenant Colonel Stuart Tootal. We would be flying to Kandahar Airfield and operating between there and a newly-built British base called Camp Bastion. At that stage, I don’t think it was much more than a few tents and a dirt runway, but it was growing by the day.

We also knew that we’d be flying on ops with the Army Air Corps’ Apache AH-1s. We’d heard mixed reports about them; at that stage they were so new to UK service that the MoD hadn’t identified a role for them and nobody really knew how they’d fare. Obviously, we’d never worked with them before and there were all sorts of rumours flying around. We’d heard they were slow and their weapon sensors weren’t very good, which, as it transpired, was absolute rubbish because they are fantastic machines. With what I know now, I wouldn’t want to fly anywhere without one.

After New Year’s Day 2006, there were really only two things on my mind: ‘A’ Flight’s impending departure for Afghanistan, and the big day for Ali and I, which we’d arranged for August. We’d planned on a big do, with our respective families, friends and work colleagues. It was to be a formal gig at the church in Odiham, with myself and the guys from the Flight in full ceremonial uniform, replete with medals, swords and white gloves. But then events conspired to bring about a radical change of plan; Ali told me she was pregnant. That changed things, especially since word started to come back from Afghanistan that things were deteriorating. Suddenly, the whole business of my deployment looked different.

About a week later, we were at home one night and I said, ‘Babe, I know your heart is set on an August wedding, but I think we should get married before I go away because we’re hearing more and more about how bad it is in Afghan.’ If anything was to happen to me, I wanted everything to be alright for Ali and the baby. Foremost in my mind was the case of Brad Tinnion, a British soldier who’d been killed on ops in Sierra Leone – because he wasn’t married to his girlfriend, the MoD wouldn’t pay her a widow’s pension and other benefits she’d have been entitled to. There was no way I was going to let that happen to Ali; her security was much more important than a glitzy wedding or the expensive dress she’d bought. Ali agreed, so we decided on a much smaller service in April, at a Register Office near our home in Brighton.

Читать дальше