I was in the hover above the boat but the intercom was dead quiet. I was sat there thinking, ‘Well they must be able to see it too, but what the fuck do I say? How do I explain this one? I haven’t got my wings and I’ve killed a crewman.’ I looked over at my instructor and his mouth was open but his stomach was heaving. He hadn’t got the mike keyed though, so it took me a second or two to realise he was belly laughing. The fuckers had planned this all along! They all had a good laugh at my expense.

It felt like everything finally came together for me at 60 Sqn; the instruction seemed better somehow, but I think it was also that we were treated like adults. We’d left the basic training behind, we’d evolved, and it felt like we were recognised for that. I only failed one sortie in the whole thirty-four weeks and that was due to no more than me having an off day – I couldn’t have found my own arse that day! I re-did it the following morning and got a very good pass, and then took the nav test, technical exercises and the final flying test all in my stride. I landed at the end of the three-hour final handling sortie that marked the end of the course, and my instructor looked at me and said, ‘Congratulations mate. You’ve got your wings.’

Getting your wings in the RAF is a huge event, but somehow it can feel like a bit of an anticlimax. Bear in mind that I’d started at RAF Cranwell in August 2000 and it was now May 2003; it felt like I’d been working for most of my adult life to get to this point. Given all that had happened, the ups and downs, I’m not sure I could quite believe that I’d done it. Finally, after everything, I was a pilot.

Graduation is a big affair, with a formal lunch and a party later in the evening, but on that morning you also find out what you’ll be flying. For me, the news was the best I could have hoped for – Chinooks! My best mate Philip and his wife came over from France, as did Mum and Dad, and everyone dressed up to the nines for the ceremony.

We’re all stood to attention in our number one uniforms and then when your name is called, you march up to the front, halt smartly, and the reviewing officer – a General of at least two-star rank – pins your wings to your chest and shakes your hand. It’s immense, actually, and when it happens you feel the enormity of the achievement wash over you. There were my parents looking at me with pride, my mate Philip smiling, and suddenly the realisation hit me. Everything I’d done, the lifelong desire to fly, the hard work, the disappointment… it all led to this point, the culmination and realisation of a dream. Finally, I could call myself a pilot.

Next stop: RAF Odiham and the Operational Conversion Flight (OCF), where I’d learn to fly the Chinook and become combat ready. First though, there was two months’ leave to look forward to…

3

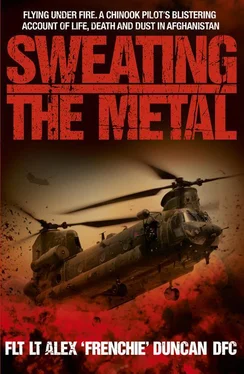

THE BEAUTY OF THE BEAST

RAF Odiham, near Basingstoke in the leafy Hampshire countryside, is home to the Royal Air Force’s three Chinook Squadrons: 7, 18 (B) and 27 Squadron. As well as being an operational unit, 18 (B) Squadron is also the training flight where pilots and crewmen learn to operate the Chinook.

There’s been an airfield at Odiham since 1925, but it became RAF Odiham on October 18th 1937 when it was officially opened by Field Marshal (then General) Erhard Milch, Chief of Staff of Hitler’s Luftwaffe. Apparently, Milch was so impressed with what he saw that he is reputed to have told Hitler, ‘When we conquer England, Odiham will be my Air Headquarters,’ and ordered his pilots not to bomb it. Whether or not this story is true, the fact remains that RAF Odiham wasn’t bombed during the war.

I drove through the gates of RAF Odiham to join the OCF in July 2003, and it’s been my home base ever since. This was a new world for me, a new start, and I wanted to set off on the right foot because until you’re combat ready, you can still lose your wings. Although they’d been tailored on to my uniform, metaphorically speaking, they were Velcroed on.

The OCF was all about operating the aircraft as opposed to simply ‘flying’ it, and there’s a crucial difference between the two terms. The fact that I could fly was a given now, so the OCF took things to another level entirely. It’s where you learn how to really get the best out of the Chinook. Take the Squirrel: all it can do is move people. The Chinook, on the other hand, is a tool: with it you can influence combat, resupply troops and bases, evacuate wounded soldiers, move them for assaults, move heavy loads… there’s just so much it can do.

When I first walked out to the aircraft, I was a well of excitement; I don’t think I’d felt anything similar since I was six and it was the run-up to Christmas. I simply had to get into that aircraft. I couldn’t wait to start it up and fly it. Outside I was the cool professional, an officer of the RAF and a competent pilot. That’s what the world saw. Inside, though, a ten-year-old kid was dancing for Harry, England and St George.

I looked up to the rotor head and it was about twenty feet above me… twenty feet! On the Griffin, it was three feet. It took four minutes just to walk around the bloody thing. And I was thinking, ‘This is a war machine; a real man’s aircraft.’ It looked like pure muscle and power. And it had this funny paradoxical charm – it was ugly but still beautiful. Its ugliness somehow highlighted and enhanced its beauty. It’s a beast, yet it’s so very graceful when airborne. I’ll never forget my first flight at the controls and the smell on walking into the cockpit, an evocative mixture of oil, hydraulic fluid and sweat. It’s strangely compelling and somehow brilliant. Every Chinook smells the same.

Your frame of reference is all based on increments; from the single engine of the Squirrel to the twin engines and complexity of the Griffin. This, though, rewrote the rule book and threw the old one out. It was Arsenal or Manchester United against a Sunday League pub team: the Chinook was in another division. Take off in the Squirrel and you’re using 95% or more of available torque. In the Chinook, I couldn’t believe that by only moving my arm by three inches I was lifting sixteen tonnes of metal and only using 50% of the available power. It had more of everything: six blades, six fuel tanks, five gearboxes, two rotor heads and two engines. It was ridiculous, and it hinted at capabilities that I had only dreamed of.

It’s huge – 99ft from end to end. It’s not a contemporary aircraft; it was designed and built by Boeing in 1962, so it saw service throughout the Vietnam War. Despite this, because there’s nothing more up-to-date out there to compare it with, it doesn’t look dated. The real beauty is its available, usable space inside the cabin, and it’s this that is the raison d’être behind the aircraft’s design. The rear is dominated by a massive hydraulic ramp, which means fast loading or unloading of whatever is in the cabin – vehicles, freight or troops (up to fifty-five of them). A tail rotor would not only hinder loading and unloading, but it would divert power from the engines and make the aircraft more difficult to manoeuvre. As it is, 100% of the power is available for lift.

Everything I’d flown up until this point had a tail rotor, but not this. Instead, it had two discs driven by two engines combined in one huge mother of a transmission. It’s called combining transmission. It splits the 3,750 horses generated by each of the two Textron Lycoming T55-L712F turbine jet engines via sync shafts to the forward and aft heads. If one engine fails, the other can drive both rotors. In each head, there’s a gear that transfers the rotation from the longitudinal plane into the vertical plane.

Читать дальше