I brief Alex. ‘Okay, I want you to put us four miles north of Edinburgh. There’s a deep valley (or “wadi”) there, and I want to be flying low through it at max speed on the approach. Bug the RadAlt down to 10ft; I’m gonna put the light on at 20 and we’re going to go in as fast and as low as we dare.’

It’s called a CAD, or Concealed Approach and Departure; when less experienced guys train in the UK they do it with speed and height commensurate with safety. The received wisdom is that speed is life, altitude is life insurance; no one has ever collided with the sky. But whoever said that was clearly unfamiliar with Helmand Province. As captain, I’m responsible for the safety of the aircraft and everyone on it. And for me, here and now, that means going low and fast.

‘Bob, get on the starboard Minigun. Standard Rules of Engagement; you have my authority to engage without reference to me if we come under fire. Clear?’

‘Clear as, Frenchie.’

I want him on the right because, looking at the topography of the area, that’s where we’d most likely take fire from. He can scan his arcs, I’ve got the front and right, and Alex and Coops have the left. We’re as well prepared as we can be, even if it does feel like we’re flying into the lion’s den.

Alex gets us into the perfect position and I drop down low into the wadi as I fly us towards FOB Edinburgh at 160 knots. Trees are rushing past the cockpit windows on either side but I’m totally focused on the job at hand so they barely register. We’re so low, I’m climbing to avoid tall blades of grass as we scream along the wadi and I’m working the collective up and down like a whore’s knickers, throwing the aircraft around. Anyone trying to get a bead on us is going to have a fucking hard time.

It’s about twenty seconds later when I see the Toyota Hilux with a man standing in the back. It’s alongside the wadi in our 1 o’clock position and about half a mile ahead. It’s redolent of one of the Technicals – the flat-bed pick-up trucks with a machine-gun or recoilless rifle in the back that caused so much mayhem in Black Hawk Down . They’re popular with the Taliban, too. Suddenly, alarm bells are ringing in my head. They’re so loud, I’m sure the others can hear.

‘Threat right,’ I shout as both Alex and I look at the guy in the truck.

My response is automatic. I act even before the thought has formed and throw the cyclic hard left to jink the cab away from danger. Except the threat isn’t to the right; the truck is nothing to do with the Taliban.

The threat lies unseen on our left, on the far bank of the wadi. A team has been brought in specifically to take us out and they have a view of the whole vista below them, including us.

I’ve flown us right into the jaws of a trap that’s been laid specially for one particular VIP that we’re carrying.

BANG, BANG, BANG, BANG, BANG!

The Defensive Aids Suite comes alive and fires off flares to draw the threat away from us; too late though. Everything happens in a nanosecond but perception distortion has me tight in its grip, so it seems like an age.

I feel the airframe shudder violently as we simultaneously lurch upwards and to the right. I know what’s happened even as Coops shouts over the comms: ‘We’ve been hit, we’ve been hit!’

There’s no time for Bob to react on the gun. The aircraft has just done the polar opposite of what I’ve asked of it. And for any pilot, that’s the worst thing imaginable – loss of control.

‘RPG!’ shouts Coops. ‘We’ve lost a huge piece of the blade!’

The Master Caution goes off and I’m thrust into a world of son et lumière . Warning lights are flashing, and the RadAlt alarm is sounding through my helmet speakers – we’ve got system failures. We’ve got sixteen VIPs in the back. And we’re still in the kill zone.

We’re going down.

1

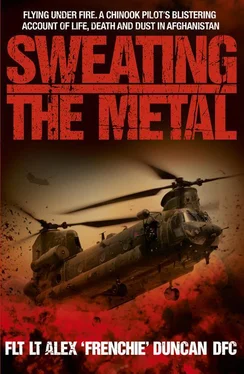

ACCROCHES-TOI À TON RÊVE

I always wanted to fly. I was six when my uncle gave me a book called Les Ailes d’or L’Aéronavale US (Golden Wings of the US Navy). Full of high-quality photos of F-14s, it awakened within me an interest in flying which then demanded attention like a recalcitrant child. Once I’d opened my mind to the concept of flight, I dreamed of being a fast jet pilot and began an enduring love affair with aviation that remains with me still.

My father is British. He’s an accountant, and my mum (who’s French) is an English teacher. They met when my dad was reading French at Oxford and, as part of his degree, went to France for a year to work as the assistant to an English teacher – that teacher was my mum. I was born in Belgium in 1976, where my father was working at the time, but moved to Paris when I was one.

Paris dominates my memories of growing up, so the city had quite an impact on my sense of identity. We lived in a spacious apartment near the Seine in a suburb to the south-west of the city. We spoke English and French at home, so I passed the exam for a bilingual secondary school and eventually graduated with my Baccalaureate. England, though, was also a huge influence on me; my paternal grandparents lived in Sevenoaks and I adored it there. I travelled there regularly from a young age and when I was older I’d spend summers there to improve my English so I had a pretty good grounding in British culture.

We travelled a fair bit when I was younger and I looked forward to the flights almost more than I did the actual destinations. I was always asking my dad to draw aircraft or make paper airplanes for me; I wasn’t so much concerned with how a plane was kept in the sky, it was the graciousness of it – there was a certain magic about the fact that it flew.

I don’t think the French Air Force ever figured in my thoughts, even from when I first dreamed of flying; it was always the RAF. When I learned about World War II, I always imagined I was in the cockpit of a Spitfire. So when it came to choosing a university, it had to be one in England. I read Aerospace Engineering at Manchester and after graduating in July 1999 (alongside my degree, I also acquired the nickname ‘Frenchie’) I was accepted into the Royal Air Force as a direct-entry pilot.

The RAF’s motto is ‘ Per Ardua Ad Astra ’, which, roughly translated, means ‘Through Adversity to the Stars’. A very loose translation might be, ‘It’s a rocky road that leads to the stars,’ and having travelled that arduous, winding and infinitely long road to gaining my wings, it’s a maxim that really means something to me.

I was well aware of what the process involved when I did my initial assessment with the RAF, but somehow, by the time I presented myself at RAF Cranwell (the RAF’s equivalent of Sandhurst) on August 6th 2000 to begin my six months of officer training, it’s like I’d forgotten. I knew on an abstract level that you don’t just join the RAF and start flying on day two, but there was still a part of me that expected to be given the keys and told to go ahead and fly!

The process of turning civilians into functioning, capable military officers is an exact science, tried, tested and honed over generations, but basically it boils down to breaking and then remaking you. The process irons out all the flaws, the bad habits, the laziness, lack of fitness and absence of discipline that are hallmarks of civilian life, and replaces them with military bearing, an ability to march, work as part of a team and lead by example. It was February 2001 when I passed out as Flying Office Alex Duncan but, because there were no slots immediately available at the Elementary Flying Training School (EFTS), I didn’t start my basic flying training until May.

Читать дальше