After all the early battles, it was clear the pattern of life had altered and that ‘we had managed to change the whole dynamic of the area from a daily commute to avoid the fighting to people living in the green zone and reoccupying their old compounds…’ But he knew the change might only be temporary. Bell was anxious about their departure. The soldiers replacing his were a smaller force without the heavy firepower of his Warriors. He worried the Taliban would encroach back.

Karzai’s study, the presidential palace, Kabul, 1 November

The intelligence chief was emphatic. ‘This is a chance to break their backbone… to break the tribal resistance in northern Helmand,’ said Amrullah Saleh, head of the NDS, Afghanistan’s secret police and intelligence service. This was the first meeting of the War Cabinet – a new body to run the war, and Musa Qala and the defection of the Taliban’s Mullah Abdul Salaam was their first subject.

‘This guy is not what you think, Mr President,’ said Dan McNeill, the NATO commander, who was on the sofa opposite Karzai. He tried to lower expectations. ‘Listen, he has got fifty-five fighters, tops, and it’s probably all he ever had. He’s a lightweight.’

But Karzai was firm. He was getting angry that nothing was being done. ‘General, I want you to protect Mullah Salaam.’

McNeill said that Task Force Helmand already had a plan ready to deploy a company of Scots Guards soldiers (Chris Bell’s armoured Warriors) up towards Salaam’s home. The whole idea stuck in McNeill’s craw. His preference was to have nothing to do with Salaam. If Salaam was a Taliban fighter worth having on your side, why did he need NATO’s protection? But he knew this man was becoming Karzai’s obsession and he knew his mission, after all, was to support the Afghan government. ‘Let’s put them in his compound for ten days and see what Salaam does and how many fighters he can recruit,’ he said.

Cowper-Coles continued his cautious approach. He suggested a less direct intervention: keeping the Warriors nearby but not actually in his village. Karzai agreed but added: ‘We have to support anyone who has turned on the Taliban. We must help Salaam without question in any circumstances !’

The president himself had just spoken to Salaam as well as to the former Helmand governor, Sher Muhammad Akhundzada. What he saw unfolding was a grand alliance of the Alizai tribe against the Taliban. Akhundzada might have imprisoned Salaam and tortured him when he was governor, but the two had now spoken and had been reconciled. Akhundzada had paid him some money.

‘Salaam has told me that the two main Taliban commanders from the Alizai will work with me,’ the president said. Musa Qala might be returned to government hands without the intervention of any NATO troops, thought Karzai. But, for now, Salaam needed to be kept alive.

‘We’re not talking here of a major military operation to take Musa Qala,’ said the British ambassador. ‘The idea instead is to let the population of Musa Qala come to us,’ he added, in what later became something of a slogan. Karzai nodded.

McNeill left the meeting unconvinced. He wondered how diplomats like Cowper-Coles and their advisers – both UK and US – could be swept along with Karzai’s rather impulsive thinking and apparently swallow this talk of a tribal solution. Perhaps they were just, well, being diplomatic – playing along with the palace politics. In McNeill’s view, Musa Qala was in the grip of drug barons and extremists. Only force was going to drive them out.

PART 3

The Taliban Strikes Back

‘ Di jin, wo tui Enemy advances, we withdraw

Di jiu, wo roa Enemy rests, we harass

Di pi, wo da Enemy tires, we attack

Di tui, wo jui Enemy withdraws, we pursue.’

Mao Tse Tung on guerrilla warfare

[14] Quoted in Colonel Thomas X. Hammes, USMC, The Sling and the Stone: On War in the 21st Century (Grand Rapids: Zenith Press, 2006), p. 46.

Operation Snakebite

At 05.00 on 2 November, a day after the War Cabinet in Kabul, a large column of British troops set off from Camp Bastion to ride to the rescue of the man the soldiers would soon call ‘Mullah Salami’.

At the head of more than fifty vehicles with 250 men and women on board, were Chris Bell’s Warrior company. They would be the strike force, along with another eighteen armoured Mastiff vehicles from the King’s Royal Hussars (the KRH). The latter’s job was to protect a logistics convoy, bringing the food, fuel and ammunition to keep the hungry armoured vehicles and their crews going. There were also mortars, assault engineers, a combat troop of Royal Marine commandos and a troop of three 105mm field guns from the Royal Artillery. Most involved would not be leaving the desert for weeks. As he surveyed the size of the force, Bell muttered: ‘This guy Salami. He better be worth it. He better deliver.

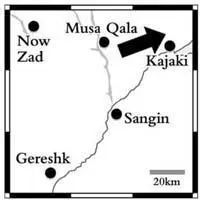

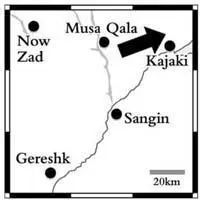

Just after first light on 3 November, a force of Royal Marine commandos crossed the Helmand River from their base in Sangin and temporarily secured the southern tip of the hostile Musa Qala wadi, allowing the convoy to cross over and reach the desert plateau around Salaam’s home in Shah Kariz .

As he moved through, Bell noted the size of operation to get his force into position – requiring the greater part of 40 Commando’s combat strength. If it took such combat power to get them in, it might take the same to get them out. ‘Having the door in and out in an unknown area controlled by somebody else is never the most comfortable feeling,’ he said later.

The mission had a name now: Operation Mar Changak, or, as the British translated it, ‘Operation Snakebite’. Bell’s orders were to reassure Salaam ‘through a visible presence around his village but do not go in’.

The second part of his orders hinted at a future, bigger operation. He was also to perform a ‘feint’, a military ruse. He was told to: ‘FEINT and DECEIVE the Taliban by feinting at their Musa Qala defences – but do not be decisively engaged.

Mackay recalled he wanted the Taliban to get a message in capitals: ‘We Are Coming To Get You .’

9. The Patrol to Khevalabad

Kajaki northern front line, 4 November, 04.40 hours

It was quiet, far too quiet. The village was empty: not a sign of life up here. Not even a scrap of paper. Not an abandoned toy, nor a rag of clothing, only a broken wooden bucket. They felt the breeze their sweat-covered foreheads – and it was the chill breath of ghosts.

Second Lieutenant Colin Lunn, the platoon commander, tried to peer through the darkness with his night-vision monocle. Through it he saw green circles of light from the soldiers’ infra-red torches dancing on the pitch-black walls.

More whispers. The scrunch on gravel as a boot slipped. Heavy breathing. A bark from a distant dog. Then Lunn quietly exhaled: ‘OK, go.’

BANG. The sound of a crashing door burst the silence. Echoing: once, twice. Then nothing. Nothing at all.

A crackle on the radio. ‘All clear, boss,’ came the thick Yorkshire voice of Sergeant Lee ‘Jonno’ Johnson.

While the armoured column of the Scots Guards and the Mastiffs passed into the desert by Musa Qala, the Taliban were showing their strength across Helmand. It was as if a hornet’s nest had been stirred. The Royal Marines at Kajaki, supported by the Afghan troops mentored by Lunn and Jonno, were about to find out what good fighters the Taliban could be.

Читать дальше