‘All those stories that came out about the Paras and later are basically embarrassing. They aren’t war!’ he exclaimed. ‘I mean, you were talking blokes put in unfair positions with thirty to forty men on a parapet dropping JDAMs [satellite-guided bombs] all around them night and day for weeks on end.’ The effect on the local population and the towns had been disastrous, he felt. And then sweeps through the green zone over the last summer had been conducted on far too great a scale, with no real focus. ‘There was no need for those blokes to die,’ he confided. ‘We have gone backwards. We have created rubble, and a load of blokes died clearing green zones, which is utterly pointless.’

There were other viewpoints. Many argued that in all wars it took time to find the right strategy and right tactics. All death was a tragedy and, in the preliminary stages of a long war, it was far too early to tell if someone’s sacrifice had achieved something meaningful. Others said the previous brigades had fought necessary ‘break-in battles’, which established a psychological advantage by demonstrating to the population that the Taliban would lose every battle with the British.

Mackay diplomatically avoided discussion on the rights and wrongs of how the war had been fought until now. But, as he told his staff when he returned from his visit to FOB Keenan, he was determined to push strategy in a new direction.

Three miles to the north-east up the Helmand River from FOB Keenan, another company of soldiers had also just arrived into the thick of fighting. Commanded by a thirty-five-year-old Oxford graduate, Major Chris Bell, the Right Flank company of the 1st Battalion, Scots Guards were mounted in Warrior armoured fighting vehicles, a new arrival to the Afghan battlefield. They were relieving 3 Company of the Grenadier Guards, who had just established a new base called FOB Arnhem.

‘When we got there, it was in a pretty bad way,’ recalled Bell. Mortars and rockets were coming in, he said, and 3 Company’s flag was peppered with shrapnel holes. Its soldiers cheered when they saw the armour on the horizon.

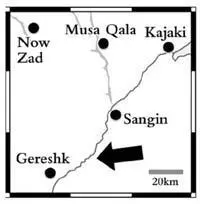

The new base was on the edge of Heyderabad, a village halfway between Sangin and Gereshk with a reputation as the ‘heart of darkness’ – a Taliban stronghold where the stares of the farmers would send a chill through your bones and where a fight was guaranteed. As Bell was discovering, it was a place that illustrated well the dilemmas of this war. It seemed to have been ‘cleared’ of Taliban more often than anywhere.

Special forces also attacked the village regularly. To the north of Heyderabad and south of Sangin was FOB Robinson, the home of Task Force 32, the American special force Green Berets that operated outside NATO command. They regularly struck the village: moving through and provoking a fight. But afterwards they returned to base. The special forces operated in small numbers. They might organize a shura after the fighting, hand out some aid or dispense a bit of medical care and try to spread good feeling. But they weren’t there to hold ground.

In the weeks that followed his arrival, Bell saw evidence that ‘attrition’ – the business of killing the enemy – was important. But the key thing was what came afterwards. Just as at FOB Keenan, when his soldiers arrived at Arnhem, they saw a landscape denuded of its population. ‘To avoid the fighting, the locals would live in the desert,’ he remembered. ‘And they would walk into the green zone soon after morning prayers, do some work and then leave well before dusk to avoid the frequent fighting that took place at that time of day. They got it down to quite an art.’

As they pushed into the green zone from FOB Arnhem, the Scots Guards were confronted by a hardline Taliban commander who called himself Mullah Basheer (not to be confused with the Mullah Bashir who defected). For the Afghan army working with them the battle against Basheer became quite personal.

The Afghans had a two-way radio, and their sergeant-major spent hours trading insults with the Taliban leader, whom the Afghans called ‘Basheer motherfucker’. Basheer would say, ‘You sold out, you’re a slave of Bush, the only thing that matters to you is the dollar, the devil’s money.’ The ANA sergeant-major would reply, ‘You’re paid in goat shit. I have money, I have schools, my children have a future.’ The British cracked themselves up laughing as they listened.

Basheer finally met his end when the Afghans heard him detail his own position on his radio. ‘I’m pinned down by mortar fire,’ he said. And ‘I’m by a tree.’ There only was one tree in the area. The tree and Basheer were destroyed with a 500-pound bomb.

Basheer’s death made a difference. Such Taliban leaders would intimidate local people. After his death, the Scots Guards began to gain some ground. The attacks lessened off, and the people started to return. Bell pushed troops out of the base, which was on the edge of the desert, into a ‘patrol base’ that was in the green zone itself and among the people. It was dangerous work. ‘They were very exposed, and our main effort as a company was to be ready to assist them and to keep them supplied,’ said Captain Matthew Jamieson, Bell’s second-in-command. The platoon was ambushed again and again as they patrolled around – often from multiple directions. And the Taliban crept up and laid mines and bombs in the fields around. One struck home, seriously injuring two men, including one lance-corporal who was hit in the eyes.

But the platoon and the company began to do small things for people like handing out blankets. They got their response. People started helping. Some began flashing lights when a Taliban patrol came close and pointing out the paths they used. Bell began to plan ambushes.

Ironically, it was 30 October, the day that Brigadier Mackay set out his new strategy for Helmand – an ‘operational design’ that called for a new emphasis away from short-lived ‘clearances’ – that Bell got his orders to move his Warrior company out of Arnhem and venture forth towards Musa Qala. He never got to do his ambushes, and the work of building up friendships with the population and of ‘pacifying’ Heyderabad had barely got going.

In the note circulated to all commanders, Mackay wrote: ‘Unless we retain, gain and win the consent of the population within Helmand we lose the campaign. The population is the prize.’ Too much emphasis placed on attrition of the enemy – killing them, in other words, with what the army euphemistically called ‘kinetic’ operations, or fighting – put consent-winning at risk and ‘in reality the non-kinetic activities barely get off the ground’. Worst of all was to judge success by body counts, the routine practice of counting up the enemy dead. ‘Body counts are a particularly corrupt measurement of success,’ he said. They might show the effectiveness of some battle tactic but they were not a sign of success. ‘Attrition of the enemy is not the object but his defeat is. This ensures that our military effort is concentrated on the “prize” – the population – and the purpose behind our presence in Helmand – pacification of the enemy and security.’ You could be fighting and winning so many battles at such a speed that you could be fooled into thinking you were succeeding but ‘every unnecessary bullet or bomb heightens insecurity and deters development’.

At FOB Arnhem, Bell figured they had already got this lesson. That morning at dawn, as he looked out from the base across the green zone, he could see a stirring. Smoke from cooking pots began to rise from the adobe compounds, and then their creaky metal doors began to open, and turbaned farmers began their daily trudge to their fields, some accompanied by young children with wheelbarrows to clear up rocks or herding out flocks of goats with wooden sticks. As his company prepared to leave this base, he could see the ‘daily commute’ from those desert mud huts was over, at least for now. The population had returned, and that was his own way of measuring their results ‘rather than by killing’.

Читать дальше