Within Breaking Bad , Walt’s existence, encounter with his own mortality and struggles to atone for his past connect to our modern anxieties over time and our continuously-in-flux identities. Our obsession with achievement and “clock time,” combined with the rising phenomena of hurry-sickness and time squeezing, perhaps provides a rationale for our always-on, always-connected culture that relishes in cell phones, social networks, and virtual representations of ourselves. While I don’t believe that Gilligan is prophesizing a ubiquitous nihilism movement of joyous sadism and narcissism, his depiction of a character who ponders and laments the “paths we take” is eerily akin to our obsession over the past, present, and future, that define our own lives.

Bergson, Henri. (1929). Matter and Memory . London: Allen and Unwin. Kindle ebook, 2012.

———. Time and Free Will . (1910). London: Allen and Unwin. Kindle ebook, 2012.

Deleuze, Gilles. Difference and Repetition . London: Athlone Press, 1994.

———. Cinema 2 . Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1989.

Freud, Sigmund. (1920). Introductory Lectures to Psychoanalysis . New York: Horace Liverlight. Kindle ebook, 2012.

Gallagher, Shaun. The Inordinance on Time . Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press, 1998.

Gleick, James. Faster . New York: Random House, 2000.

Gonzales, Rachel, Larissa Mooney, and Richard A. Rawson. 2010. “The Methamphetamine Problem in the United States.” Annual Review of Public Health. 31. 385-398. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.012809.103600.

Harvey, Mick. “Out of Time Man.” http://www.justsomelyrics.com.

Heideggar, Martin. Being and Time , translated by John Macquarrie and Edward Robinson. New York: Harper, 1962 (1927).

Heisenberg, Werner. Physics and Philosophy: The Revolution in Modern Science . New York: Prometheus Books, 1999.

Hume, David. A Treatise on Human Nature. London: Oxford University Press. Kindle ebook, 2000.

Husserl, Edmund. On the Phenomenology of the Consciousness of Internal Time . London: Kluwer, 1991.

Leong, Susan, Teodor Mitew, Marta Celleti, and Erika Pearson. “The Question Concerning (Internet) Time.” New Media and Society . 11. (2009): 1267-1285.

Maxwell, Jane Carlisle and Beth A. Rutkowski. “The Prevalence of Methamphetamine and Amphetamine Abuse in North America: A Review of the Indicators, 1992—2007.” Drug and Alcohol Review 27 . (2008): 229-235.

Moshe, Mira. “Media Time Squeezing: the Privatization of the Media Time Sphere.” Television and New Media. 13:1. (2012): 68-88.

Nietzsche, Friedrich. The Gay Science, with a Prelude in Rhymes and an Appendix of Songs . New York: Vintage, 1974.

———. 2012. “Truth and Lies in an Extra-Moral Sense.” http://academics.eckerd.edu/instructor/starkjl/jls--inactive/405/September13/Nietzsche.pdf.

Shaw, Spencer. Film Consciousness: From Phenomenology to Deleuze . London: McFarland and Company, 2008.

Swift, Jonathan. (1892). Gulliver’s Travels . London: George Bell and Sons. Kindle ebook, 2012.

Turkle, Sherry. Alone Together . New York: Basic Books, 2011.

———. “Can You Hear Me Now?.” Forbes. 7 May 2007. http://www.forbes.com/free_forbes/2007/0507/176.html.

Widder, Nathan. Reflections on Time and Politics . State College: Pennsylvania State University, 2008.

Chapter 3

HEISENBERG: EPISTEMOLOGICAL IMPLICATIONS OF A CRIMINAL PSEUDONYM

Alberto Brodesco

Who is Walter White? What is his profession? The early impressions that Breaking Bad give of its main character’s occupations are very contradictory. The first time we see him, in the cold open of “Pilot” [1] If we suppose that the diegetic time concurs with the year of broadcasting (2008).

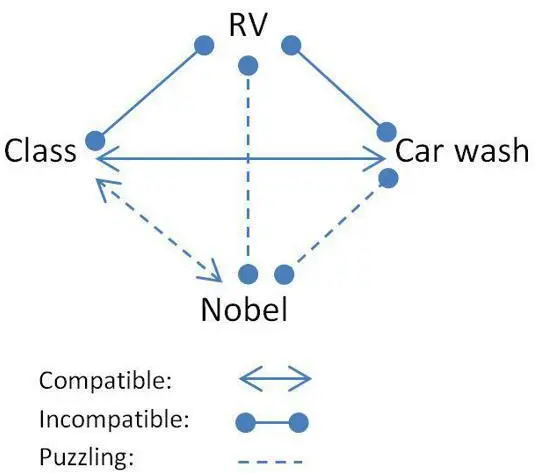

(01/20/2008), he is driving a RV in the desert in his underwear; then he is at home, in front of a plaque commemorating his contribution to research having been awarded the Nobel Prize; we learn later that he teaches chemistry at the J. P. Wynne High School; after school he reaches a car wash, where he works as an employee to supplement his income. The four jobs do not match each other at all.

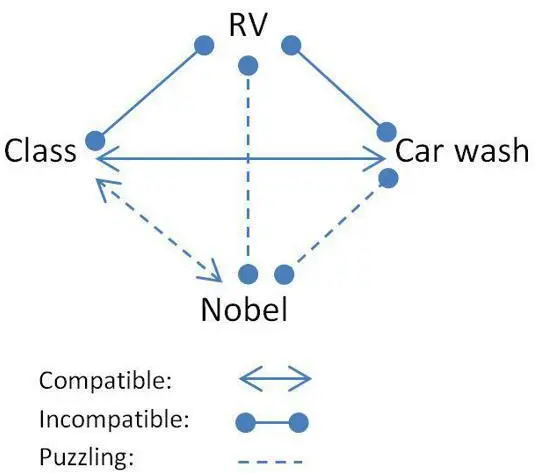

A scheme of the compatibilities of Walter White’s occupations.

As summarized in the above scheme, the illegal work performed inside the RV is in obvious contrast with all the other three legal activities. The work at the school is compatible with the one at the car wash, if we assume that the teacher is underpaid and he needs to moonlight. But in relation to his Nobel Prize research this job in education raises some questions. Why should a top level researcher settle teaching in a high school? What’s even more perplexing is the arrow between the Nobel and the Car wash. Why should such a scientist work part-time at a car wash? Breaking Bad is a tale of schizophrenia. Teacher, car wash employee, Nobel prize co-winner, methamphetamine manufacturer, criminal. Walter White is all of these characters. It is impossible to identify this man with a single and recognizable profile. In a society that often bases its judgment and attribution of social value on profession, it is very difficult to decide if White is a successful man or a loser. This indeterminacy or uncertainty that will develop further and further through the five seasons of the series is one of the great textures of Breaking Bad ’s plot.

Following Walter we ultimately enter or get to know very different scientific milieus—legitimate ones like the classroom or Gray Matter company and illegitimate ones, like the RV and Gustavo Fring’s drug laboratory. But in these “professions” there is not just a division between legal and criminal activities but also one between big and small (or smallest) science (see Price 1963), the first leading to awards and glory, the latter writing formulas on a blackboard in front of a class of bored students. For the high school job Walter White is evidently over qualified. His big science becomes small when transferred into a classroom and returns big again when (illegally) transported into the RV. There, out of place, applied to drug manufacturing, Walt’s chemistry majestically gets back its strength and creativity.

Teaching seems indeed to provide just frustration to Mr. White. The only real restitution he gets from his high school employment is, quite ironically, that he recognizes a drug dealer escaping from a window as his former student Jesse Pinkman. In “Green Light” (4/11/10) Walter will definitely leave the school. White is now a full-time criminal and a full-time scientific genius. To give the viewer an idea of Walter’s professional dissatisfaction, the pilot permits a close look at the Nobel Prize plaque. Walter wakes up early on the morning of his fiftieth birthday. In the dining room, he exercises on a primitive stair-master, in front of which is appended a framed paper that says “Science Research Center, Los Alamos, New Mexico hereby recognizes Walter H. White, Crystallography Project Leader For Proton Radiography, 1985, Contributor to Research Awarded the Nobel Prize.” From this plaque we gather significant information. Walter White worked, when he was around twenty-seven years old, in a nuclear physics program at Los Alamos.

If we leave the fictional world and take a look at the real Nobel winner list, we can verify that the Chemistry prize in 1985 went to Herbert A. Hauptman and Jerome Karle with the following motivation, “for their outstanding achievements in the development of direct methods for the determination of crystal structures.” [2] Please see http://www.nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/chemistry/laureates/1985/ .

This is certainly a clue to Walter White’s meth crystals. But given the “Proton Radiography” specialization of Walt’s study we may also take a look at the Physics Nobel Prize of the same year, awarded to Klaus von Klitzing “for the discovery of the quantized Hall effect.” [3] Please see http://www.nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/physics/laureates/1985/ .

We are in the field of quantum mechanics. In light of Walter White’s further career we take note of both of these pieces of information. The plot does not specify the pathway that drives White from Los Alamos Science Research Center to J. P. Wynne High School. Between the two there is certainly Gray Matter, a successful technology company deserving a Scientific American cover (“Gray Matter,” 02/24/08) co-founded by Walter White with a friend of the time, Elliott Schwartz. For unknown reasons, Walt later left this position. He will accuse his former associates of having built an empire on his work (“Peekaboo” 4/12/09). The huge success of Gray Matter is an additional element leading Walt to drug manufacturing. As he explains to Jesse (“Buyout” 8/19/12), he had sold his share of the company to Elliott for $5,000, while Gray Matter now had a net worth of $2.16 billion. In front of this empire, Walter strives to build another, a criminal one.

Читать дальше