Waiting, of course, is a very large part of writing.

Writing “Hernes,” a novella about ordinary people on the Oregon coast, involved a lot of waiting. Weeks, months. I was listening for voices, the voices of four different women, whose lives overlapped throughout most of the twentieth century. Some of them spoke from a long time ago, before I was born, and I was determined not to patronise the past, not to take the voices of the dead from them by making them generalised, glib, quaint. Each woman had to speak straight from her center, truthfully, even if neither she nor I knew the truth. And each voice must speak in the cadence characteristic of that person, her own voice, and also in a rhythm that included the rhythms of the other voices, since they must relate to one another and form some kind of whole, some true shape, a story.

I had no dragon to carry me. I felt diffident and often foolish, listening, as I walked on the beach or sat in a silent house, for these soft imagined voices, trying to hear them, to catch the beat, the rhythm, that makes the story true and the words beautiful.

I do think novels are beautiful. To me a novel can be as beautiful as any symphony, as beautiful as the sea. As complete, true, real, large, complicated, confusing, deep, troubling, soul enlarging as the sea with its waves that break and tumble, its tides that rise and ebb.

An unpublished piece in which I return to and go on from some of the themes and speculations of the essay “Text, Silence, Performance” in my previous nonfiction collection Dancing at the Edge of the World.

MODELS OF COMMUNICATION

In this Age of Information and Age of Electronics, our ruling concept of communication is a mechanical model, which goes like this:

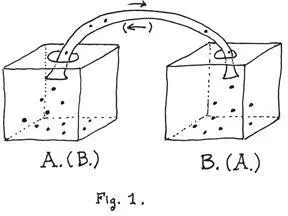

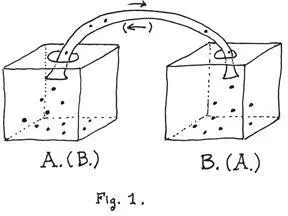

Box A and box B are connected by a tube. Box A contains a unit of information. Box A is the transmitter, the sender. The tube is how the information is transmitted—it is the medium. And box B is the receiver. They can alternate roles. The sender, box A, codes the information in a way appropriate to the medium, in binary bits, or pixels, or words, or whatever, and transmits it via the medium to the receiver, box B, which receives and decodes it.

A and B can be thought of as machines, such as computers. They can also be thought of as minds. Or one can be a machine and the other a mind.

If A is a mind and B a computer, A may send B information, a message, via the medium of its program language: let’s say A sends the information that B is to shut down; B receives the information and shuts down. Or let’s say I send my computer a request for the date Easter falls on this year: this request requires the computer to respond, to take the role of box A, which sends that information, via its code and the medium of the monitor, to me, who now take the role of box B, the receiver. And so I go buy eggs, or don’t buy eggs, depending on the information I received.

This is supposed to be the way language works. A has a unit of information, codes it in words, and transmits to B, who receives it, decodes it, understands it, and acts on it.

Yes? This is how language works?

As you can see, this model of communication as applied to actual people talking and listening, or even to language written and read, is at best inadequate and most often inaccurate. We don’t work that way.

We only work that way when our communication is reduced to the most rudimentary information. “STOP THAT!” in a shout from A is likely to be received and acted on by B—at least for a moment.

If A shouts, “The British are coming!” the information may serve as information—a clear message with certain clear consequences concerning what to do next.

But what if the communication from A is, “I thought that dinner last night was pretty awful.”

Or, “Call me Ishmael.”

Or, “Coyote was going there.”

Are those statements information? The medium is the speaking voice, or the written word, but what is the code? What is A saying?

B may or may not be able to decode, or “read,” those messages in a literal sense. But the meanings and implications and connotations they contain are so enormously complex and so utterly contingent that there is no one right way for B to decode or to understand them. Their meaning depends almost entirely on who A is, who B is, what their relationship is, what society they live in, their level of education, their relative status, and so on. They are full of meaning and of meanings, but they are not information.

In such cases, in most cases of people actually talking to one another, human communication cannot be reduced to information. The message not only involves, it is , a relationship between speaker and hearer. The medium in which the message is embedded is immensely complex, infinitely more than a code: it is a language, a function of a society, a culture, in which the language, the speaker, and the hearer are all embedded.

“Coyote was going there.” Is the information being transmitted by this sentence—does it “say”—that an actual coyote actually went somewhere? Actually, no. The speaker is not talking about a coyote. The hearer knows that.

What would be the primary information obtained by a hearer who heard those words spoken, in their original language and in the context where they might have been spoken? Probably something like: Ah, Grandfather is going to tell us a story about Coyote. Because “Coyote was going there” is a cultural signal, like “Once upon a time”: a ritual formula, the implications of which include the fact that a story’s about to be told, right here, right now; that it won’t be a factual story but will be myth, or true story; in this case a true story about Coyote. Not a coyote but Coyote. And Grandfather knows that we understand the signal, we understand what he’s saying when he says, “Coyote was going there,” because if he didn’t expect us to at least partly understand it, he wouldn’t or couldn’t say it.

In human conversation, in live, actual communication between or among human beings, everything “transmitted”—everything said—is shaped as it is spoken by actual or anticipated response.

Live, face-to-face human communication is intersubjective. Intersubjectivity involves a great deal more than the machine-mediated type of stimulus-response currently called “interactive.” It is not stimulus-response at all, not a mechanical alternation of precoded sending and receiving. Intersubjectivity is mutual. It is a continuous interchange between two consciousnesses. Instead of an alternation of roles between box A and box B, between active subject and passive object, it is a continuous intersubjectivity that goes both ways all the time .

“There is no adequate model in the physical universe for this operation of consciousness, which is distinctively human and which signals the capacity of human beings to form true communities.” So says Walter Ong, in Orality and Literacy .

My private model for intersubjectivity, or communication by speech, or conversation, is amoebas having sex. As you know, amoebas usually reproduce by just quietly going off in a corner and budding, dividing themselves into two amoebas; but sometimes conditions indicate that a little genetic swapping might improve the local crowd, and two of them get together, literally, and reach out to each other and meld their pseudopodia into a little tube or channel connecting them. Thus:

Читать дальше