Near the end of the expedition, Cook was killed by natives in the Hawaiian Islands, and it was Bligh who brought Cook’s ship, HMS Resolution, back to England, which was a pretty good bit of navigating for a man not yet twenty-five.

War broke out with France, and Bligh did a good job in the fleet, earning a promotion to lieutenant, got married to Elizabeth Bethman, was appointed master of HMS Cambridge, and got to know and become friends with Fletcher Christian, who taught him how to use the sextant and who, he wrote in his diary, treated him like a “brother.”

Then disaster struck in the form of peace. England cut its navy in half and Bligh, like just about every officer, had his pay cut in half. But his wife was rich and she had connections, so Bligh was given command of a merchant ship, the Britannia, which sailed to the West Indies and back on a regular schedule. Fletcher Christian also served aboard, and their friendship grew and solidified.

In 1787 Bligh was given command of the Bounty, technically HMAV (Her Majesty’s Armed Vessel) Bounty, for which he had to take another pay cut. Navy men were paid less than merchant marine officers. But he saw it as a chance for promotion. The deal was that if he made it back from the South Pacific in one piece he would be promoted to captain. And that was a big prize.

A lot of things were happening in the world at about that time. In Europe the French Revolution was getting off the ground, in America the Constitution was being voted on, and in England George III was being battered by the prestigious Royal Society to do something— anything—that would promote England scientifically or economically. The war with the colonies had been lost; it was time to get past it. England needed to save some serious face in the world arena. And Bligh, who needed to do the same for his own career, was just the man for the job.

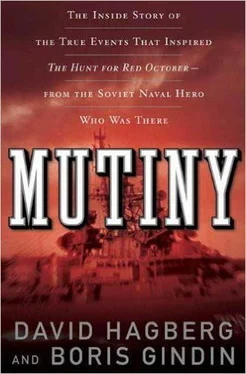

The situation wasn’t all that dissimilar to Potulniy’s. He came from a naval background, and already as a sixteen-year-old he had been accepted to attend the Frunze Military Academy. He did his apprenticeship aboard a number of warships, and when the Storozhevoy’s keel was laid he was tapped to be the ship’s first commander.

That was a big opportunity for Potulniy to prove himself. A lot of things were happening in the world in 1974. The Cold War between the Soviet Union and the United States was at its height, the United States had beaten Russia to the moon, and already the seeds of the people’s discontent with Moscow were like brush fires, easy to spot but difficult to extinguish.

And there were a lot of similarities between Christian and Sablin. Both men had been born to well-to-do families; both knew what they wanted to do very early on—Christian went to sea at sixteen, and Sablin applied for and was accepted to the Frunze Military Academy at the same age. Both were about the same height and build, both had dark hair and complexions, and both men were described by friends as being mild, open, humane, generous, and sometimes a little conceited.

Bligh and his crew were to sail the Bounty down to Tahiti in the South Pacific via Cape Horn at the southern tip of the Americas to take on as many breadfruit plants as they could carry and bring them to the West Indies. The plantation owners wanted something cheap to feed their slaves, and breadfruit, which grew in Polynesia but not in the West Indies, was just the thing. This trip was just as much political as it was humanitarian. The plantation owners were a rich and therefore a powerful political faction, and the king wanted to appease them.

The Bounty had started her life as a coal ship named Bethia. And despite the bad luck associated with changing a ship’s name, as soon as the collier had been converted into a warship she got a new name. In effect Bligh and his crew were the first to sail the Bounty, as Potulniy and his crew were the first to sail the Storozhevoy.

At 215 tons, the Bounty was ninety feet on deck and was armed with four four-pounders and ten swivel guns. Because space had been made to carry the breadfruit plants, there wasn’t a lot of room aboard for the young crew, who ranged in age from fourteen to thirty-nine.

Like with Potulniy and his crew there was a certain distance between Bligh and his sailors. It was a gap that was filled by Sablin aboard the Storozhevoy and by Christian aboard the Bounty. The ordinary crewmen liked and respected those officers, who both had sympathetic ears.

Bligh had learned early in his career that ships are run by men and that men needed to be well cared for if they were to do their jobs well. To combat scurvy, a disease resulting from deficiency of vitamin C that was very common in those days, Bligh made sure that sauerkraut was served at every meal. And he also knew that exercise was vitally important, so he brought aboard a blind fiddler named Michael Byrne to play music to which the men could dance. No one liked it, but the crew was kept fit. Just like the Russian farm boys aboard the Storozhevoy exercising every day up on deck, it was one of those systems in the military that worked.

The Bounty’s crew bitched about the food and they bitched about the exercise, but Bligh just stamped around on deck and swore at them. He wasn’t going to give any consideration to their complaints. He was the captain and that was the end of it. If they wanted to grumble, they could bitch to Christian for all Bligh cared.

But Bligh, like Potulniy, wasn’t a bad man, even though he was mostly aloof from his crew. For instance, he split the ship’s company into three watches, instead of the normal two, which was unusual for that day. It made duty much easier. The men could get some rest between watches. And after trying to get around Cape Horn for nearly thirty days, being pushed back into the Atlantic by storm after storm, he thanked his crew for a valiant effort, then turned tail and headed for the Pacific by the longer, but easier, route across the Atlantic and around the southern tip of Africa.

The Bounty arrived in Tahiti in the late fall of 1788 and had to remain at anchor for nearly six months until it was the proper season to harvest the immature breadfruit plants. This was Bligh’s big mistake. Six months with no sea duty, at an island filled with good-looking and very willing Polynesian women, for whom white men were a novelty, corrupted the crew. Compared to England, and especially compared to life aboard ship, Tahiti was a paradise. Many of the men had girlfriends, and in six months a lot of the relationships were just as strong as any new marriage. When it was time to leave, a lot of the men didn’t want to go. A few of them even deserted, hiding up in the hills, where they hoped to wait it out until the Bounty sailed away.

But Bligh would have none of that. He took a party and searched the island, finally rounding up the deserters after three weeks of tromping through the mountains and jungles. But he was a humane man. Instead of flogging them and then hanging them from the yardarms, as was the practice, he just had them flogged.

The Bounty finally weighed anchor in the spring of 1789, loaded to the gills with breadfruit plants and a very unhappy crew, miserable that they were being made to leave paradise. Bligh stormed around the deck, swearing and bitching, especially at Christian, all day long, every day, and yet each night Christian was invited to dine with the suddenly civilized captain.

Like Potulniy, who never suspected that Sablin would turn against him, Bligh never had the slightest suspicion that Christian would lead a mutiny. Such an act was utterly unthinkable.

A couple of weeks out from Tahiti, Christian decided to build a raft, jump ship, and somehow try to make it back to Tahiti, where he’d had a warm relationship with the chief’s daughter. He confided in one of the midshipmen, who warned that there were sharks in the water.

Читать дальше