“Good,” Sablin says. “Now get yourself to the midshipmen’s dining hall and wait for me.”

“What about the bullets?”

“As soon as I’m finished with the captain,” Sablin says. “Now go!”

When Shein disappears down the corridor, Sablin takes a moment to compose himself before he rushes to the captain’s cabin and without knocking throws the door open.

Potulniy, in shirtsleeves, is sitting at his desk doing some paperwork, and he looks up in surprise. “What is it, Valery?”

“Captain we have a CP!” Sablin shouts. It is a Chrez’vychainoy Polozhenie, a situation.

“What has happened?” Potulniy demands, getting to his feet.

“Some men are drinking belowdecks, in the supply compartment,” Sablin reports. “Captain, I think they mean to do some damage unless they’re stopped.”

“We’ll see about that,” Potulniy snaps. “Come with me.”

He rushes forward and down ladder after ladder, deep into the forward bowels of the ship, his zampolit right on his heels.

Reaching the sonar compartment, Potulniy looks over his shoulder. “Here?”

“Yes, Captain, just inside,” Sablin says.

The captain pulls open the hatch and climbs down into the compartment. The moment his head clears the level of the deck, Sablin slams the hatch shut and dogs it down.

“Valery, what are you doing?” Potulniy shouts. At this point he has no comprehension of what is happening.

“Saving the Soviet Union,” Sablin calls back, and even to his ears the statement seems grandiose.

“What are you talking about? Let me out of here. That’s an order!”

“I can’t do that, Captain, not until later. For now, most of the officers and I are taking control of the ship.”

“Mutiny?” Poltuniy screams. “You bastards. You’ll all hang.”

“What I’m doing is just as much for your benefit as for the Rodina’s. Can’t you see?”

“I thought you were my friend.”

“I am. Believe me, Anatoly, I am your best friend.”

“Then why are you doing this? Have you gone insane?”

“We’re going to broadcast on radio and television directly to the people.”

“Broadcast what?”

“A call for revolution. A return to the true meanings of Marx and Lenin. We’re tired of the lies, tired of the stagnation, tired of having no say in our future. Can’t you see—?”

Potulniy slams something that sounds like a piece of metal against the hatch. “You bastard! You miserable fucking traitor! Let me out now!”

Sablin steps back, his heart pounding nearly out of his chest, until he finally catches his breath. He makes certain that the hatch is truly locked, then turns and heads back up to the midshipmen’s dining hall, for the next part of the mutiny to unfold.

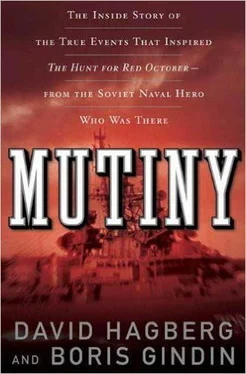

The act of mutiny is punishable by death in just about every navy in the world. Even failing to report a suspicion that someone else aboard ship is about to commit mutiny can be punishable by death. National governments take this crime very seriously.

Technically, mutiny is a crime of nothing more than disobeying a legal order. If the captain says, “Scrub the decks,” and the sailors refuse, they may be court-martialed for mutiny. The reason the crewmen disobey the order doesn’t matter; all that matters is that the order was a lawful one.

That means the captain of a ship has been placed in charge of the vessel and his crew. Every order the captain issues is, by definition, a legal one, unless of course it goes against all common sense or is clearly against the Geneva Convention. But even then the issue is almost impossible to prove, because the benefit of the doubt always lies with the captain. According to the British Royal Navy’s Articles of War (1757), which most nations, including the Soviet Union, adopted:

ARTICLE 19: If any person in or belonging to the fleet shall make or endeavor to make any mutinous assembly upon any pretence whatsoever, every person offending herein, and being convicted thereof by the sentence of the court martial, shall suffer death: and if any person in or belonging to the fleet shall utter any words of sedition or mutiny, he shall suffer death, or such other punishment as a court martial shall deem him to deserve: and if any officer, mariner or soldier on or belonging to the fleet, shall behave himself with contempt to his superior officer, being in the execution of his office, he shall be punished according to the nature of his offence by the judgment of a court martial.

ARTICLE 20: If any person in the fleet shall conceal any traitorous or mutinous practice or design, being convicted thereof by the sentence of a court martial, he shall suffer death, or any other punishment as a court martial shall think fit; and if any person, in or belonging to the fleet, shall conceal any traitorous or mutinous words spoken by any, to the prejudice of his majesty or government, or any words, practice, or design, tending to the hindrance of the service, and shall not forthwith reveal the same to the commanding officer, or being present at any mutiny or sedition, shall not use his utmost endeavours to suppress the same, he shall be punished as a court martial shall think he deserves.

Probably the most famous of all mutinies was that of HMS Bounty in the spring of 1789, when First Officer Fletcher Christian and twenty-six sailors of the forty-four crewmen arrested Captain William Bligh and the eighteen remaining crew and set them adrift in a twenty-three-foot launch in the middle of the Pacific Ocean. That story and its aftermath have been the stuff of books, articles, novels, and, in the last seventy years or so, movies.

In at least one aspect the incident aboard the Bounty was similar to that of the Storozhevoy —how the officer who mutinied felt about his captain. Aboard the Bounty, Christian and Bligh were close personal friends, and aboard Storozhevoy Sablin and Potulniy had gotten along from day one. They had a mutual respect for each other. That’s one of the reasons the captain so blindly followed Sablin’s lead down into the bowels of the warship, where he could so easily be locked up.

When the Bounty sailed from Spithead, England, two days before Christmas 1787, she carried Captain Bligh, who was the only commissioned officer aboard, and a crew of forty-five men. Most crewmen aboard British men-of-war at that time were pressed into service. Very few of the ordinary sailors were volunteers. In fact, the author Samuel Johnson complained often and bitterly about the practice, writing that “no man will be a sailor who had contrivance enough to get himself into jail, for being in a ship is like being in jail with the chance of being drowned… and a man in jail has more room, better food, and commonly better company.”

But it was different aboard the Bounty because every man in the crew had volunteered for the cruise. So there wasn’t supposed to be any trouble. At least that’s what Bligh and Christian thought at the beginning.

Bligh was a short, stout man with thick black hair, pale blue eyes, and a milky, almost albino complexion. But he knew what he was doing. He’d gone to sea at the age of sixteen as an ordinary seaman, but less than a year after he’d signed on he was given his warrant as a midshipman because he was bright, energetic, and earnest. He loved being in the navy, and he put every bit of his heart and soul into being the best officer he could be.

By the time Bligh had turned twenty-three his reputation was such that Captain James Cook tapped him to be the navigator for the famous South Pacific explorations of the fabled Tahiti and beyond. When the expedition was all over, Cook couldn’t write enough good things in the ship’s log about Bligh, and in fact the nautical charts that the young navigator drew from that expedition were so good, so precise, that many of them were still in use more than two centuries later.

Читать дальше