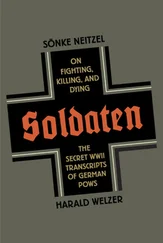

The study makes it clear that the great mass of Wehrmacht soldiers were not interested in politics, that politics did not shape perception among the soldiers, and that ideology played at most a subordinate role in the consciousness of most Wehrmacht soldiers. Of course, German soldiers did not exist in a vacuum during the Third Reich – they were part of National Socialist society, accepting and shaping its social framework. Soldaten elucidates, however, that the degree to which specific National Socialist values can be traced to their frames of reference was limited, at least in the second half of the war. We do not doubt that there was a hard core of soldiers who combined set pieces of Nazi ideology into a more or less self-contained understanding of the world. And we also point out that ideologised soldiers were found with particular frequency in the Waffen-SS or in the elite units of the Wehrmacht. Soldaten therefore does not completely neglect the influence of ideology on action or the perceptions of simple soldiers, but it does seek to relativise them significantly. Practically everyone was certainly loyal to the Nazi state, and, of course, this cannot be confused with a crude ideologisation. Most of them may not have seen at the time what we see today in the Nazi state, yet they certainly perceived a distorted image. It is also interesting that soldiers made a distinction between Hitler and the Nazi regime; for most of them, Hitler was a sort of pater patriae , not the National Socialist ‘Führer’ who was responsible for war, murder and war crimes.

Many soldiers indeed were anti-Semites and anti-communists, which definitely made it easier for them to pledge their loyalty to the Nazi state. The critical fact remains, however, that their perception of war, their interpretation of events, their expectations for the future and so on were not determined primarily by political or ideological patterns or set pieces in the narrower sense, but rather by their experiences on the front, of the battles in which they found themselves. This is why approval of the Nazi state changed significantly as the defeats began to occur. Their loyalty to their nation, and above all to the institution of the Wehrmacht, remained unbroken. And this was the actual secret of the Nazi state: the loyalty of the soldiers to the Wehrmacht was absolutely unshakeable because they viewed it as an efficient and successful organisation in which they could fulfil their duty for the Fatherland, regardless of social class or political conviction. Yet many soldiers did not see this during the war – even if this may strike us as astonishing today.

Soldaten therefore goes against Omar Bartov’s thesis of the National Socialist infiltration of Wehrmacht soldiers. And it relativises the concept of the Volksgemeinschaft (national community), at least in its most extreme manifestation, as Thomas Kühne recently argued. [e] Kühne, ‘Belonging and Genocide’.

Kühne’s thesis is that the exclusion of the Jews from German society, and their murder, was a decisive factor in creating the national community. The creation of this community was therefore achieved through crimes (in both the narrow and broad sense of the term), because these performed an integrating social function. Mass murder, according to Kühne, bestowed a feeling of identity sui generis upon the national community as a whole in the Third Reich. The claim here is that the Nazi state successfully overcame societal rifts qua crimes. Perpetrator research has in fact shown how groups are constituted and consolidated as communities in and through the act of mass murder (culture of participation, outsiders play a key role for the inner differentiation of the group).

Whether the creation of community through mass crimes – above all through the Holocaust – united Germans as a whole seems, however, a questionable argument in light of the research results from Soldaten , because the group of perpetrators directly involved in these crimes is too small, knowledge of it was too diffuse among too many people, and this line of thinking was not in the front and centre of their perceptions. The idea of creating a community through a broadly understood meaning of crime seems problematic, even if we add the murder of civilians in the hinterlands in the course of the partisan war, or Soviet prisoners of war, and if we look at the Wehrmacht instead of the entire German people. For members of the Wehrmacht, their perceptions of war were shaped indelibly by their everyday experiences at the front from 1939 to 1945: overwhelming sensory impressions of battle, privations, fear, joy, waiting, free time, gossip and chin-wagging, enthusiasm for technology etc. These experiences certainly included war crimes, as the transcripts make abundantly clear.

Interestingly, however, acts of violence that we would clearly define today as crimes and transgressions of the norm were often simply not perceived by soldiers as such, and therefore could not have created a sense of solidarity: the experience of extreme violence on a daily basis, plundering, forced labour by civilians, rapes, even scorched earth and executions often seemed little more than events that one need not worry about, because they were so pervasive and completely normal. This just seemed what war was supposed to be about.

In the secretly taped conversations of German soldiers, they described Allied carpet bombing of German cities as a terrible yet ‘normal’ act of violence in this kind of war, not as a crime. Massacres of Jews and the murder of Soviet prisoners of war were certainly appraised differently – namely, as a horrible crime. The soldiers, however, did not draw any further conclusions from such acts of violence and did not question the war, the Wehrmacht or even the state. Crimes occupied a central role in the interpretations of a very limited few, displacing a positive self-understanding and instigating something like long-term shame. Like in other social communities, Wehrmacht soldiers developed an astonishing capacity for blocking out unpleasantness, dismissing such occurrences as isolated cases or somehow recasting the event to prevent calling their world view into question.

It is certainly right to focus contemporary research on the crimes of the Wehrmacht, yet we cannot commit the error of analytical narrowness, confusing what we hold to be a central feature of war with what the soldiers perceived as central to war. Crimes were not the central concern of contemporary perception among Wehrmacht soldiers – and the Holocaust was most definitely not.

Soldaten became a bestseller in Germany just a few days after its publication, and it has been discussed from the USA to Australia. Interestingly, the book’s actual findings have scarcely been appreciated, especially outside Germany. What seemed most spectacular was the nonchalance in speaking about violence, the brutality of the language, the joy of killing. It seemed that once more we had proof of how horrible the Wehrmacht had been and in fact was, yet this has been known for a long time. The brutality in itself is therefore not the essential point; instead, it is the matter-of-course, everyday normality of this brutality – and above all the timelessness of speaking about war in this way. This phenomenon is by no means limited solely to the Wehrmacht: it involves adjustment within the shortest period of time to the frame of reference of war and the consideration as completely normal of things that, in civilian life, we would interpret as revolting, horrible or even criminal.

Many readers outside Germany found it difficult to follow this interpretation of the Wehrmacht; indeed, they found it difficult to follow any analysis at all. Some expressed regret that Soldaten was not just another set of published transcripts. In the final analysis, some believed that the authors’ analysis could be safely ignored, because people already knew everything about the reasons for the actions of the Nazi Wehrmacht.

Читать дальше

![Traudl Junge - Hitler's Last Secretary - A Firsthand Account of Life with Hitler [aka Until the Final Hour]](/books/416681/traudl-junge-hitler-s-last-secretary-a-firsthand-thumb.webp)