A Surrealist Mixed Spectacle of Deliverance and Death

While everyone in Europe awaited the invasion, what it meant for an individual depended on where he or she happened to be in the summer of 1944. Anne Frank was in hiding in Amsterdam. For her and her family, the “long-awaited liberation” meant hope. “It fills us with fresh courage and makes us strong again,” she wrote in her diary on the sixth of June. 17Anguish was what Françoise Seligman was feeling in Paris that morning. “A kind of inner panic paralyzed me,” the French woman remembered. “If they fail, if they leave, the proof will have been made that France has become an impregnable bastion of Nazi power, and we will never ever be liberated.” 18For the civilians in Normandy, where the battle claimed both homes and human lives, the landings took on yet another meaning. A woman named Yvonne living near Mortain called her day of liberation a “surrealist mixed spectacle of deliverance and death.” 19

The burden of loss was not new on D-day. The invasion had created a reason for the French to endure the weary days of scarcity, humiliation, and deprivation. At the same time, for months before the landings, Allied bombardment had wreaked havoc with Norman lives. Military planners had launched a bombing campaign the previous fall to prevent the Nazis from moving troops and supplies to the front in the opening weeks of the Normandy campaign. 20So as not to betray the location of the Allied landings, bombing occurred over all of France, with the targeting of bridges, roads, and railways as well as oil depots and other German installations. In the year 1944 alone, 503,000 tons of bombs fell on France, and 35,317 civilians were killed. 21The populations of Nantes, Cambrai, Saint-Étienne, Caen, and Rouen all suffered heavy casualties, with hundreds or thousands reported dead or wounded. 22A bombardment of B-17s on a train in which resistance member Jean Collet was traveling appeared to him as a “strange ballet of death: you saw the bombs unleashed from the plane and falling in your direction. Then they disappeared from view due to their rapidity of speed. Then one instant after a terrifying whistle they would explode in a dreadful crash. Meanwhile we were flattened against the ground to avoid the explosions.” 23Civilians suffered the devastation of homes, workplaces, and farms. As a result, many felt more fear than hope about the coming invasion. “The landings are both yearned and dreaded,” wrote a Caen prefect in early 1944, “one hopes for a decisive victory while also making a selfish wish that it won’t happen where one lives.” 24

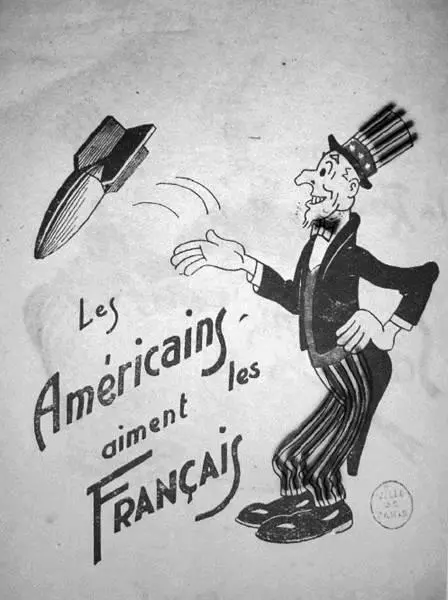

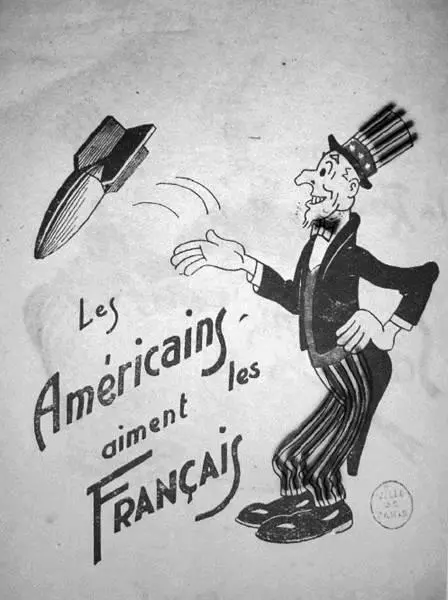

It was only human to want the Allies to come—only somewhere else. But specific circumstances also aggravated fear and resentment. For one, the Nazis chose to use bombardment like a hammer to nail in anti-Allied feeling. In widely disseminated handbills and other forms of propaganda, the Germans claimed that the United States had a “Machiavellian plan,” which was to take over the French Empire, destroy France, and colonize Europe itself. 25(See figure 1.1.) Because they could kindle anti-Allied feeling with the destruction caused by the bombing, the Nazis provided neither a warning system nor a temporary shelter for the Normans. To counter such propaganda, the Allies air-dropped leaflets reassuring civilians. “We know that these bombardments add to the suffering of certain among you. We do not pretend to ignore that,” conceded one brochure. “Move away as much as possible from ironworks, railway stations, junctions, train depots, repair shops.” 26The warnings were considered to be earnest but pointless as civilians had no choice but to work and live around strategic targets.

FIGURE 1.1. “The Americans Love the French.” Courtesy of Bibliothèque Historique de la ville de Paris.

A second major issue was imprecision in bombing. The “flying fortress” B-17 bomber—the pride of the American air force—provoked a clenched French fist for missing its target so often. The Normans considered the British to be superior to the Americans in precision bombing. 27As early as October 1943, the Gaullist resistance organ CFLN (Comité français de la libération nationale) reported that the French were sick “of accumulating ruins and deaths without results.” 28While some civilians found comfort in the French adage that to make an omelet, you have to break eggs, others wondered, “why was it necessary to break so many?” 29Nor did civilians perceive any rational plan, according to the CFLN. Bridges were destroyed several times over in a period of days, then left alone for months, so that the Germans could rebuild them. 30The bombings were “barbarian,” and they should be stopped. 31In their reports on public opinion, the CFLN claimed civilians believed Nazi warnings concerning American imperial ambitions. Besides economic greed, the Americans were guilty of harshness in the Versailles treaty, indifference to German rearmament in the 1930s, slowness in entering the war, and collaboration with Vichy official Admiral Darlan in North Africa. Even the delay in the invasion became a kind of “treason.” 32

Because the CFLN, following de Gaulle, distrusted the Allies, it no doubt exaggerated the anti-Americanism rippling through the French population. 33But you didn’t have to be in the Gaullist resistance to be fed up with Allied bombing. 34French refugees interviewed by the BBC after their arrival in England also complained of the “appalling” effects of bombing throughout the nation. In Nantes, they related, “there was such violent irritation” that when an American pilot, shot down on French soil, offered a civilian a cigarette, he spat on it. Another refugee complained of Modane, near Grenoble, where the Allies dropped their bombs four kilometers away from the railway station despite having been given detailed maps. 35The deep-down, gnawing fear was that the bombs would keep coming while the invasion would not. France would be destroyed but not liberated. “It would be possible to annihilate Europe without annihilating the war,” wrote Alfred Fabre-Luce in his journal just before the invasion. 36

The prelanding destruction of the French countryside eroded faith in the Allies. For months, civilians’ feelings toward them had been a muddle of admiration and rage. Allied victories in North Africa had given the French their first reason to believe that the Nazi war machine could be beaten. 37American success in bringing clothes, cigarettes, and food to civilians in Tunisia and Algeria raised hopes everywhere on the continent. 38But anger still warped the joy of liberation. “Having stood by impotent, enraged and revolted by the savage destruction” of his hometown, Augustin Maresquier was determined to suppress his happiness upon seeing his first American. But his joy, he realized, was stronger than his own resolution not to feel it. 39Fourteen-year-old Claude Bourdon had the same “strange surprise” when she was liberated: despite her fury concerning the destruction of her home, “my heart began to beat violently; I was ready to burst into sobs of joy.” 40

The damage—and resentment—would only increase after the landings. Neither the destruction nor the anger stopped. The Battle of Normandy was long, discouraging, and costly. In contrast to the battle-weary residents of northern and eastern France, Normans had not experienced a war firsthand for many generations. 41Strategic coastal towns such as Cherbourg and Saint-Malo were heavily bombed. Le Havre was nearly destroyed, as were Caen and Saint-Lô. The wreckage was psychological as well as physical. “Nothing could be more painful,” wrote George Duhamel in the fall of 1944, “than to be wounded by one’s own friends.” 42Once again, superfluous bombing sparked outrage. Civil Affairs reported on 28 July that the French were furious about “what is considered to be unnecessary bombing and shelling of towns.” 43While the Allied objective was to destroy German installations and troops, in many cases, such as Caen, bombing continued even though the Germans had supposedly left. 44In Le Havre, French officials angrily pointed out that some three thousand civilians had been killed while fewer than ten German bodies had been found. 45As late as mid-October, Civil Affairs was still reporting that “resentment is more widespread and does not appear to be lessening” in Le Havre. 46

Читать дальше