In the summer of 1945, thousands of American GIs overran Le Havre, a port city in Normandy. With the war over, the soldiers were waiting for a boat home. A year earlier the Allies had freed the region from German control. The people of Le Havre were not ungrateful, but they now found their city virtually occupied by their liberators. Le Havre was in a state of siege, bemoaned the mayor Pierre Voisin in a letter to Colonel Weed, the American regional commander. The good citizens of his city were unable to take a walk in the park or visit the grave of a loved one without coming across a GI engaged in sex with a prostitute. At night, drunken soldiers roamed the street looking for sex, and as a result “respectable” women could not walk alone. Not only were “scenes contrary to decency” taking place day and night, complained Voisin, but “the fact that youthful eyes are exposed to such public spectacles is not only scandalous but intolerable.”

Voisin had already dispatched policemen to patrol the parks, but the GIs ignored them. He had tried putting the prostitutes on trains to Paris, but flush with cash, the women got off at the first stop and took taxis back. So the mayor was writing Weed yet again. Could the Americans construct a regulated brothel north of town? Voisin suggested they set up special tents in a location convenient to their camps. The brothel would be overseen by US military police and medical personnel to make sure sexual activity was medically safe as well as discrete. Prostitutes would be treated, and venereal disease rates would drop. The city could be allowed to get on with life.

But Voisin was wasting his time. In a return letter, Weed washed his hands of the crisis. Prostitution was Voisin’s problem, not his, Weed replied. If the prostitutes were sick, the GIs could not be held accountable. Regulation of sex by the US military was out of the question. High command would not allow it, mostly because they feared that journalists would report on any such operation and news of GI promiscuity would make its way back home. Weed also shrugged off the growing problem of venereal disease. Although he made some vague promises about providing medical personnel, nothing materialized. Voisin was soon writing another letter, this time to his own superiors to ask for money. Public funds were running dry; the venereal wards were overwhelmed; the sick women had nowhere to go. What was the mayor to do? 1

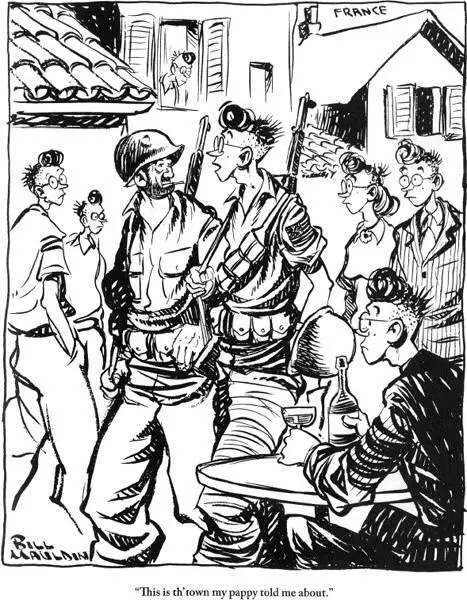

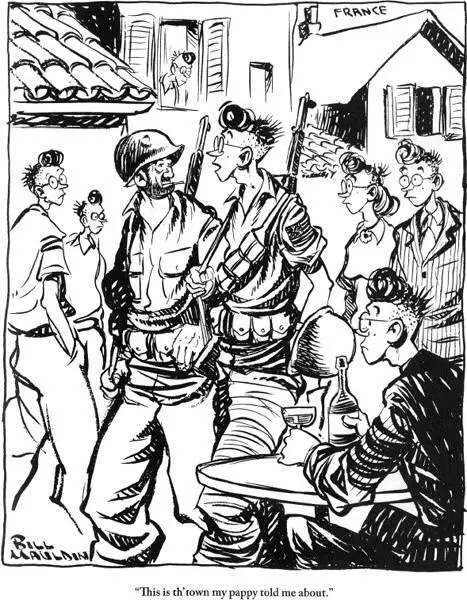

Weed was not the only American commander to dismiss the French on matters of sex. Like many officers, he probably thought they would not even notice the sight of sex in public. Wasn’t sex a French specialty? Why then would public sex bother them? Indeed, the GIs had grown up hearing stories of sexual adventure from fathers who fought in France in 1917–18. Such stories led a generation of men to believe that France was a land of wine, women, and song. Bill Mauldin’s 1944 cartoon of a soldier proclaiming “This is th’town my pappy told me about” played on this image of an eroticized France. (See figure Intr.1.) In the months before and after the landings, military propaganda gave such preconceptions new life for a second generation of soldiers. 2As a result the general opinion along the line was that, in Life journalist Joe Weston’s words, “France was a tremendous brothel inhabited by 40,000,000 hedonists who spent all their time eating, drinking [and] making love.” 3

This sexual fantasy, in turn, had an important political effect, which was to complicate the postwar French bid for political autonomy. At all levels of military command, officials shared the prejudice that the French were morally degraded and therefore perhaps not able to govern themselves. By so flagrantly disregarding sexual and social norms in Le Havre, the GIs also expressed their moral condescension, relaying the message that it was hardly necessary to behave in a civil manner toward the French. If GIs were having sex wherever they pleased, that was because the inhabitants of Le Havre—as respectable members of a community, as citizens of a sovereign nation—had become invisible to them. Weed’s response to Voisin also registered growing confidence on the part of the US military that it could have the world its way. That confidence dictated that American soldiers needed an outlet for their sexual energies, so French women should provide one. It valued the health of the American soldier more than that of the French prostitute. Finally, US military policy protected American families from the spectacle of GI promiscuity while leaving French families unable to escape it.

FIGURE INTRO. 1. Bill Mauldin cartoon. “This is th’ town my pappy told me about.” From Stars and Stripes , 6 September 1944. Used with permission from Stars and Stripes. © 1944, 2012 Stars and Stripes.

Sexual relations gained political significance during the years of the American presence in France because the period was transitional for both nations. The United States was crossing the golden threshold of global power. By contrast, France was waking up to its many losses. The defeat of 1940 had been a catastrophe, the German occupation a humiliation. Now the presence of American soldiers on French soil meant liberation, yes, but also evidence of international decline. That disparity in war fortunes meant the two nations had many matters to work out between them. First was the issue of French sovereignty: Would the army impose a military government like the one already established in Italy? Or would the French be allowed to govern themselves? Also vital was the role of the United States in Europe. Its military victory on the Continent was absolute, and it had established bases throughout France and Germany. How much would this triumphant new power come to dominate a broken Europe?

Much can be learned about these questions, this book argues, by looking at how the US military managed GI sexual intimacy in France. There is no question that the United States took advantage of its military presence in France to influence a great deal of economic and political life there. Managing sex between GIs and French women was a key component of this control. The US government harbored no imperial ambitions within Europe, but it did seek to control a European balance of power for several reasons: to create a frontier against the Soviet Union, to “protect” Europe from communism, and to delineate a sphere of influence that would enhance its global power. 4While the landings were a noble mission, they also opened a pivotal phase in the rise of American political dominance. As the historian Irvin Wall has put it, by the end of the war, “the Americans had tried to, and discovered that they could not, make and break French regimes. But they had also become accustomed to the exercise of an unprecedented degree of meddling in internal French affairs.” 5

The question of French autonomy had not yet been decided at the time of the Allied invasion. The US military seemed determined to wrest sovereignty from its only credible bidder, Gen. Charles de Gaulle. Neither Franklin D. Roosevelt nor Winston Churchill formally recognized de Gaulle as a sovereign leader, despite his control over much of the Resistance and the Committee of National Liberation (CFLN), which operated at both local and national levels. The Anglo-American military alliance was not committed to a free France, and planned to install a military government called AMGOT, modeled after the Allied one established in Sicily in 1943. 6When the Allies finally decided on a date for the landings, de Gaulle was told only at the last minute, and given no assurance of sovereignty. In Roosevelt’s opinion, since the French people could not vote, there was no way of knowing if they wanted de Gaulle as their sovereign leader. 7Furthermore, without consulting the general, the Allies also printed a new currency for soldiers about to embark for Normandy.

Читать дальше