Fortunately for Hitler, the Allies’ momentum faltered as the weather began to deteriorate and on the 19th a violent storm halted all shipping in the English Channel for three days. The Allies’ military build-up virtually ground to a halt, delaying 20,000 vehicles and 140,000 tons of stores. In the meantime, distracting Hitler’s attention back to the Eastern Front, on 22 June the Russians launched Operation Bagration, which would ultimately smash Army Group Centre in spectacular fashion.

Due to the bad weather the Germans were granted a vital breathing space during which they were able to reorganise their forces and move without Allied air strikes. Some felt that prior to D-Day Schweppenburg overdid night training, but he was in fact exercising great foresight. Allied firepower was greatly curtailing German freedom of movement during daylight hours. The deterioration in the weather would have been an ideal time to launch a counterattack, but the opportunity was lost.

The Allies still had the initiative and if they could maintain it the Germans would remain off balance. Montgomery declared he would tie the panzers down on the eastern flank in the Caen-Caumont sector, destroying them in a series of offensives that would look like an attempted break-out toward Paris, while the Americans mopped up the German forces in the Cotentin Peninsula and took the port of Cherbourg prior to their own break-out attempt.

The Americans knew they were not facing the Germans’ top panzers. What tanks the German forces could muster on their western lank were mainly Czech or French models, such as the French-equipped training unit Panzer Ersatz und Ausbildungs Abteilung 100 and Panzer Abteilung 206, which could scrape together about seventy tanks of indifferent quality. Only Panzerjäger Abteilung 243 was equipped with any notable armour, totalling twenty-four self-propelled guns and assault guns. The main garrison units were the 243rd and 709th Infantry Divisions, which had been reinforced by the 3rd Parachute Division and the 77th Infantry Division moved up from Brittany.

Once the Americans reached Barneville-sur-Mer on the west coast of the Cotentin Peninsula on 18 June they set about pushing north and securing Cherbourg. They opened their attack four days later, the defenders resisted until the 26th before surrendering, although pockets of resistance continued for a further two days. By the end of the month the Americans had captured over 39,000 German prisoners and were now ready to strike southward. Both Panzer Abteilung 100 and 206 ceased to exist.

The week-long British Epsom offensive, west of Caen toward Evrecy and Esquay southwest of the city, launched on 25/26 June was intended as a preemptive strike to tie up German armour reinforcements. Barely a week later, the British and Canadians conducted Operation Charnwood, a frontal attempt on Caen, though they only succeeded in taking the northern half of the city.

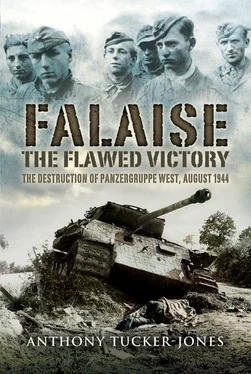

By late June there were almost eight panzer divisions between Caen and Caumont on a 20 mile (32km) front facing the British 2nd Army. In particular the 2nd, 12th SS, 21st Panzer, Panzer Lehr and the 716th Infantry Divisions were all tied up in the immediate Caen area. Facing the British were approximately 725 German tanks, while on the American front there were only 140. Caen became the bloody fulcrum of the whole battle; here the cream of Panzergruppe West would be ground down in a series of unrelenting British attacks culminating in Operation Goodwood.

The desperately needed German infantry divisions that should have freed up the panzers for a counterstroke remained north of the Seine. Hitler held them back presumably because he still feared an attack across the Pas de Calais. By the end of June it was evident that von Rundstedt’s ‘crust-cushion-hammer’ tactics had failed despite the slowly increasing number of panzer divisions; tied down in the face of Allied firepower and attacks, the panzers could do little more than fire-fight as the situation developed. To make matters worse, by the beginning of July the unrelenting operational commitment of the panzers was taking its toll, 58 per cent of the Panthers and 42 per cent of the Panzer IVs were in the maintenance depots.

General Dollmann, 7th Army’s commander, died at his field HQ on 28 June; it is unclear if he had a heart attack or committed suicide, but SS-Obergruppenführer Paul Hausser from the II SS Panzer Corps assumed command. SS-Obergruppenführer Wilhelm ‘Willi’ Bittrich who had fought in Poland and France, subsequently commanding the 2nd SS and 9th SS Panzer Divisions took charge of the II SS Panzer Corps.

At this point Rommel and von Rundstedt drove the 600 miles (960km) to Berchtesgaden to see Hitler. They tried to prevail upon him to permit their forces to withdraw behind the Seine. In addition, Rommel wanted to strengthen the weakened Panzergruppe West and 7th Army with 15th Army’s reserves and those forces tied up with Army Group G, way to the south. To their dismay, Hitler steadfastly refused; instead of heeding the advice of his two highly-experienced generals, he chose to do what he always did when anyone stood up to him.

Lacking friends at court, Rundstedt’s days as C-in-C West were numbered. On 3 July Hitler accepted von Rundstedt’s offer to stand down on health grounds and on the same day the hapless Schweppenburg was removed as commander of Panzergruppe West. Rundstedt held Hitler’s Chief of Staff, Field Marshal Keitel, partly responsible for this state of affairs; indeed Rundstedt was contemptuous of Keitel’s skills as a military coordinator. Removing two such senior generals at a critical moment seemed madness and can have done little to reassure Rommel of his future.

At the beginning of July Panzergruppe West’s Chief of Staff informed Rommel: ‘The morale of the troops is good, but one can’t beat the materiel of the enemy with courage alone’. They were outnumbered four to one in tanks in the British sector; in the American sector it was worse, eight to one.

Günther von Kluge was summoned from the Eastern Front to replace von Rundstedt, but he was no more able to stabilise the situation than his predecessor. He did not last long following the failure of the Mortain counter-offensive in mid-August; summoned to Berlin he shot himself. Walter Model was then recalled from the Eastern Front to oversee the final defeat in Normandy.

General Heinrich Eberbach was appointed in Schweppenburg’s place. He had commanded Panzer Regiment 35 within the 4th Panzer Division and fought well in Poland, Belgium, France and Russia. At Baranovitch he had gone to the aid of the 3rd Panzer Division and, despite securing victory, for a short time faced charges of disobeying orders. Whilst on the Eastern Front Eberbach had been wounded a number of times and suffered with continuing kidney problems; nonetheless, in August 1943 he was promoted to General der Panzertruppen. By December he was recuperating in Germany, but had then returned to Russia.

In Normandy one of Eberbach’s first actions was to see the newly-appointed von Kluge and then Rommel to get appraised of the current situation facing Army Group B, Panzergruppe West and 7th Army. The fighting had so far cost the Germans 87,000 casualties, as well as 417 irreplaceable panzers and assault guns. Afterwards he visited the 12th SS Panzer Division defending Caen on 7 July and ordered elements of the 21st Panzer Division to support the beleaguered 16th Luftwaffe Field Division.

By the first week of July, elements of the 2nd SS Panzer Division were making their presence felt on the American front, supporting elements of the 17th SS Panzergrenadier Division, which had been their since early June. By mid-July the 1st SS, 21st Panzer and Panzer Lehr Panzer Divisions had been withdrawn into reserve, but Montgomery’s Operation Goodwood prevented everything except Panzer Lehr from shifting west.

Читать дальше