One key armoured command was the I SS Panzer Corps, this had been created in July 1943 in Berlin Lichterfeld, though it officially came into being at Beverloo, Belgium. SS-Obergruppenführer Sepp Dietrich, former commander of the 1st SS Panzer Division, assumed control, while the SS Panzer Corps of SS-Obergruppenführer Paul Hausser was redesignated II SS Panzer Corps. The latter had been initially created in the Netherlands in July 1942 as the SS Panzer General Kommando.

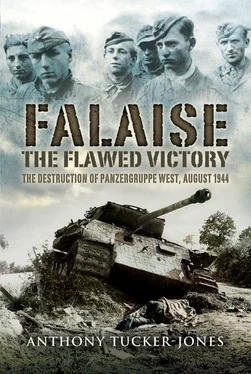

Dietrich’s command had spent much of the summer of 1943 helping seize control of northern Italy following the country’s defection to the Allies. His Corps moved to Septeuil, west of Paris in April 1944 where the 1st SS, 12th SS and Panzer Lehr Panzer Divisions as well as the 17th SS Panzergrenadier Division were placed under its direction, forming part of Panzergruppe West.

Most of the panzer divisions deployed in Western Europe were refitting after heavy combat on the Eastern Front. In the north, stationed in 15th Army’s area of responsibility, were the 2nd, 19th (scheduled to return to Poland), 21st, 116th, Panzer Lehr, 1st SS and 12 SS Panzer Divisions. To the southeast in 19th Army’s area were the 9th and 2nd SS Panzer Divisions; while to the southwest with 1st Army were the 11th Panzer and 17th SS Panzergrenadier Divisions.

Organisation of the Heer and Waffen-SS panzer divisions was similar, with a panzer regiment of two battalions or abteilungen , a Sturmgeschütz and/or Panzerjäger abteilung . The nominal structure also included two panzergrenadier regiments (one motorised and one armoured), artillery, engineer, lak, medical and reconnaissance units. In reality the structure and the manpower of the units varied according to local circumstances. In Normandy the German infantry divisions’ anti-tank battalions largely consisted of towed weapons, but six Panzerjäger Battalions were also equipped with Marder self-propelled and Sturmgeschütz assault guns.

Reserve panzer units were very sparse in the summer of 1944. In the spring of the previous year just four training Reserve Panzer Divisions, the 155th, 178th, 179th and 273rd, were formed in France. Their task though was to provide replacement cadres for existing units rather than being combat formations in their own right.

Nevertheless, in March 1944, because of the worsening situation on the Eastern Front and in Italy and the expected opening of the second front, OKW began considering using the 155th, 179th and 273rd to constitute three new panzer divisions. For the combat cadres it was decided to employ those divisions used to rescue Army Group South on the Eastern Front, namely the 9th Panzer and 10th and 16th Panzergrenadier Divisions. They were instructed to be combat ready by 1 May1944, which in reality was a tall order.

General Adolf Kuntzen’s LXXXI Corps based in Rouen, on the Seine, north of Paris had the only anti-invasion experience. His HQ was responsible for 302nd Infantry Division, charged with defending Dieppe and the surrounding area, along with the 336th Infantry Division. It had fallen to Kuntzen’s corps with the assistance of the 10th Panzer Division to halt the Allies’ Dieppe raid. The LXXXI Corps’ control of an armoured division had been short-lived and by June 1944 its subordinate units consisted of the 245th and 711th Infantry Divisions and the 17th Luftwaffe Field Division. Kuntzen and his staff would play a very belated and minor role in the Normandy campaign.

Conflict in the High Command

To defeat an Allied invasion, C-in-C West favoured the ‘crust-cushion-hammer’ concept, the crust being formed by the static sea defences, the cushion by infantry reserves and the hammer by the armoured divisions held further back. Schweppenburg, commander of Panzergruppe West, agreed with Rundstedt in believing the panzer divisions should be kept inland, ready to encircle the Allies as they tried to advance on Paris. His command had been set up with responsibility for training the panzer divisions, but it was also conceived as a headquarters, subordinated to the German 7th Army, to coordinate a panzer counterattack in the event of an invasion in Normandy.

Schweppenburg was a highly experienced panzer corps commander. A First World War veteran, he had served in London in the mid-1930s as the German Military Attaché. He then commanded 3rd Panzer Division for the attack on Poland and promptly fell out with his corps commander, General Heinz Guderian; Schweppenburg had been superior to Guderian, until the latter was put in charge of Hitler’s panzer forces in 1938. During the invasion of France in 1940 he had commanded the XXIV Panzer Corps and had subsequently commanded a panzer corps with Guderian’s 2nd Panzer Army.

By April 1943 Schweppenburg, commanding the LXXXVI Corps at Dax (located at the end of the Pyrenees), found himself lumbered with the proposed Operation Gisela designed to seize the ports along the northern coast of Spain. He dubbed the plan to seize Bilbao with a division and Madrid with four others as ‘folly.’ Luckily Hitler opted not to alienate General Francisco Franco’s Spain. Schweppenburg was transferred to assume command of Panzergruppe West in October 1943, now notably full of admiration for what Guderian had achieved with the panzertruppen .

In contrast Rommel wanted the panzers well forward to deal with the Allies as soon as they waded ashore. He felt any air borne landings in the rear could be easily dealt with by those troops to hand. Rommel had made his name as a panzer leader in France and North Africa and had also orchestrated the successful seizure of northern Italy. He knew only too well how potent Allied air power could be, which is partly why he advocated keeping the panzers near the coast. He did not reckon with the power of the Allies’ naval gunner, which would greatly hamper the panzers even when they did get near the beachhead.

During the Dieppe raid the nearest German armour within striking distance belonged to the 10th Panzer Division, under General Wolfgang Fischer, stationed at Amiens 60 miles (96km) away. The 1st SS Panzer Division, under Sepp Dietrich, was 80 miles (128km) away north west of Paris. It had fallen to the 302nd Infantry Division under Generalleutnant Conrad Hasse to thwart the seaborne attack.

Ironically, the Germans afterwards noted bombastically: ‘Our rapid intervention and the powerful aspect of the panzer division made a great impression on the populace’. Although the 10th Panzer and 1st SS Panzer Divisions had gone on alert at 0625, 10th Panzer did not head north until 0900 and then it was hampered by inadequate maps and worn out vehicles. Its progress was far from proficient and the Luftwaffe was equally slow off the mark to react. Fischer arrived at Dieppe just as the survivors were surrendering at 1308 hours.

While Hitler was understandably impressed by Rommel’s proposals, it was Schweppenburg who swayed the day by personally visiting him to argue that the panzers should be held under a centralised command in the forests astride the Seine. Schweppenburg felt the greatest threat would be from an airborne landing. He was also of the view that the Allies should be allowed to penetrate inland before being counterattacked. Hitler backed von Runstedt and Schweppenburg, refusing Rommel’s request to deploy the 12th SS at the base of the Cotentin Peninsula and for Panzer Lehr to deploy to Avranches.

The conflict over this issue reached such a tempo that Rommel and Schweppenburg fell out. ‘I am an experienced tank commander,’ Rommel told Schweppenburg, ‘you and I do not see eye to eye on anything. I refuse to work with you anymore’. On a personal level, Rommel can only have felt slighted after a subordinate commander whose responsibility was ostensibly to oversee panzer training had undermined his authority. It must have further irked him that even if Panzergruppe West did become an operational command he expected it to come directly under Army Group B’s control. In the event this was not to happen.

Читать дальше