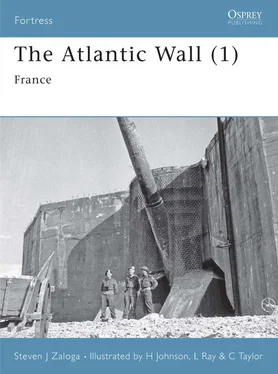

Among the massive coastal artillery casemates on the Pas-de-Calais was Turm West of MKB Oldenburg MAA.244, armed with a 240mm SK L/50, originally a Tzarist 254mm gun captured in 1915 and re-chambered by Krupp. The two casemates of this battery were specialized SK designs built to the heavy Standard A with 3m-thick walls and ceilings. In the foreground is one of the associated H621 personnel shelters. (Author’s collection)

This large-scale raid was a fiasco and demonstrated that even a modestly fortified port could be defended. Dieppe was held by two under-strength battalions of Infanterie Regiment 571, 302.Infanterie Division, a typical second-rate occupation unit. The seacoast town was partially fortified with some concrete bunkers plus machine guns and other weapons in field entrenchments. While the fortifications were not especially numerous by later standards, the cliffs on either side of the 1.5km-wide beach provided a natural overwatch position for enfilade fire along the coast. A pair of naval artillery batteries were located on either side of the town, armed with a total of ten 105mm guns, but they played little role in repulsing the main attack. Once the raid began the German commander rushed the divisional anti-tank company to the town which played a role in stopping the Canadian Churchill tanks trapped on the beach by the seawalls, tank traps and treacherous shingle. For the Wehrmacht, the Dieppe raid re-affirmed the value of coastal defenses in enabling badly overextended units to defeat amphibious attacks. It also reinforced the Wehrmacht’s belief that the main Allied invasion would be directed against a port.

Some German officers felt that the success in repelling the Dieppe raid was exaggerated, distorting later plans for the defense of France. General Freiherr Leo Gehr von Schweppenburg, who later led the Panzer forces in France during the Normandy campaign, argued that:

The basic misconception of the anti-invasion defense stemmed from the opinions based on the Dieppe raid. The personal ambition of a certain military personality in the west [Gen.Maj. Kurt Zeitzler, chief of staff of OB West] and above all the subsequent propaganda nonsense had changed the story of the Anglo-Saxon experimental raid on Dieppe into a fairy tale of defensive success against a major landing attempt. This was all the more irresponsible as captured orders clearly indicated a time limit for the operation. The self-satisfied interpretation could never be dislodged from the minds of high command. Together with Rommel’s fallacious theories of defense, it was responsible for the grotesque German situation [in France].

In some cases, the Germans integrated existing French coastal defense positions into the Atlantic Wall. This triple-tier fire-control post was part of MKB Seeadler located on Pointe du Brulay near Cap Lévy east of Cherbourg, armed with French 194mm guns in kettle emplacements. (NARA)

For the Allies, Dieppe provided valuable lessons into the realities of assaulting fortified ports, even one as weakly protected as Dieppe. It convinced British planners that it would be wiser to stage future assaults away from ports against more thinly defended beaches. These lessons were at the heart of the plans for Operation Neptune , the D-Day amphibious assault in Normandy two years later.

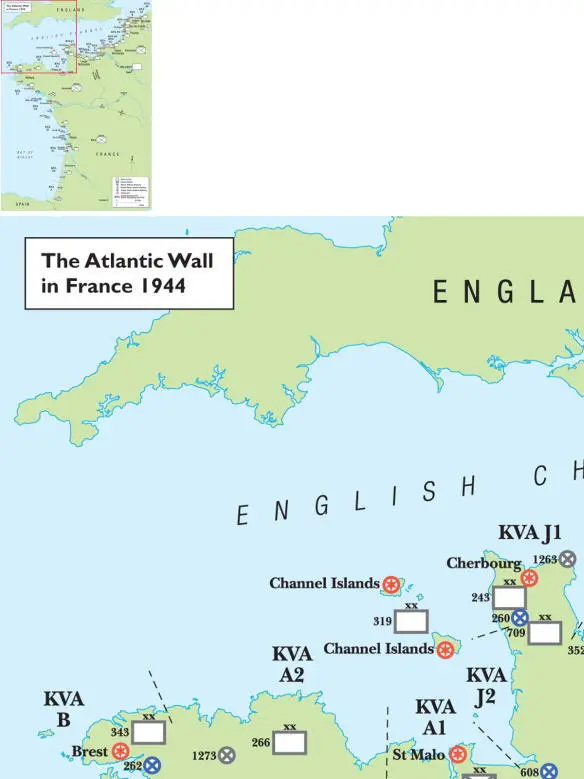

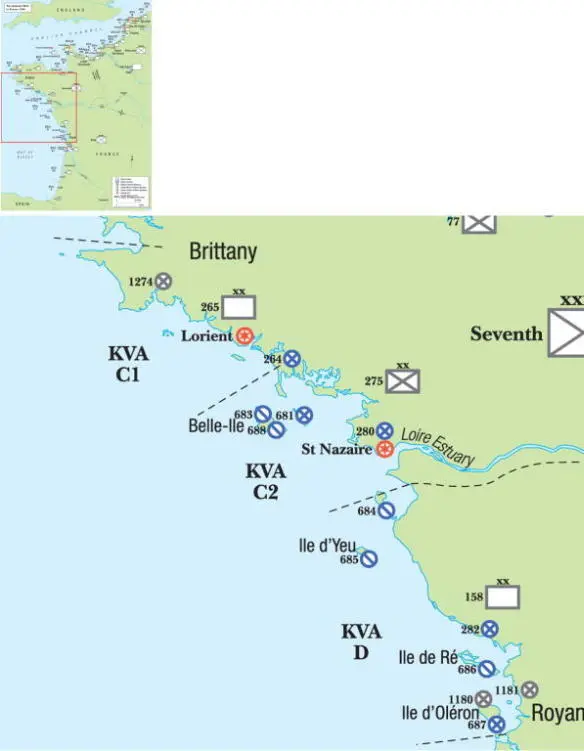

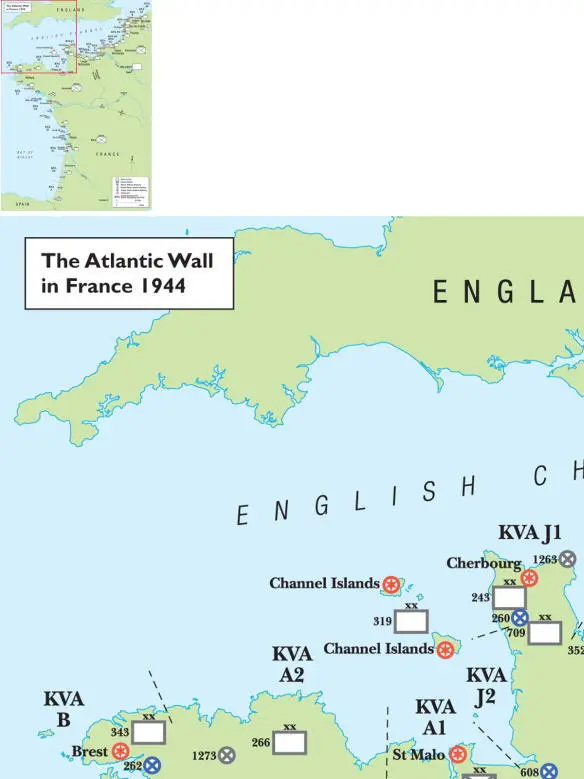

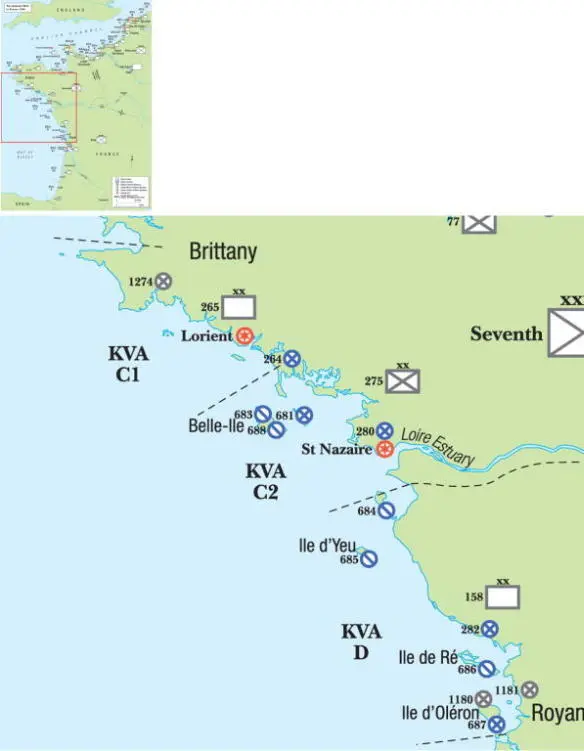

In 1943–44, OB West designated several port areas as fortresses ( Festung ) included Dunkirk, Calais, Boulogne, Le Havre, Cherbourg, St. Malo, Brest, Lorient, St. Nazaire, the Gironde estuary and the Channel Islands. The US invasion of French North Africa in November 1942 prompted the Germans to occupy Vichy France, adding another coastal region to the list. The Mediterranean coastal fortifications were dubbed the Südwall and are outside the scope of this book. In the event, the Mediterranean ports of Marseilles, and Toulon retained the lesser and earlier designation as “fortified areas,” as did some Atlantic ports such as La Rochelle and Bayonne. The Festung ports were to be fortified on both the seaward and landward sides and were to be provisioned to be able to hold out for at least three months.

Kriegsmarine defenses in France

German naval forces in occupied France in 1943-44 were under the command of Marine-Gruppekommando West based in Paris, led by Admiral Theodor Krancke since April 20, 1943. MGk-West in turn was divided into regional sector commands of which the most important was Admiral Kanalküste (Channel Coast Admiral), which replaced the earlier Marine-Befelshaber Kanalküste (Channel Coast Naval Command) in April 1943 and which was led by Vizeadmiral Friederich Rieve. The other sectors of the coast were the Marbef Bretagne for Brittany and the Admiral Atlantikküste for the sector from St. Nazaire to Spain. These regional commands were in turn sub-divided into nine Seekommandant (Seeko) of which seven were along the Atlantic Wall:

| Command |

Headquarters |

| Seeko Pas-de-Calais |

Calais |

| Seeko Seine-Somme |

Le Havre |

| Seeko Normandie |

Cherbourg |

| Seeko Kanalinseln |

Guernsey |

| Seeko Bretagne |

Brest |

| Seeko Loire-Gironde |

St. Nazaire |

| Seeko Gascogne |

Royan |

The Seeko headquarters in turn controlled a variety of naval units in their sector. The most important were the harbor commands with a Hako ( Hafenkommandant : port commander) in the larger ports and a Haka ( Hafenkapitän : harbor captain) in the smaller ports. These commands usually included a port police force ( Hafenüberwachung ). The Kriegsmarine had an active program for using naval mines for coastal defense, but this subject is largely outside the scope of this book. Of somewhat more relevance are controlled mines for harbor defense. The raids on St. Nazaire and Dieppe made it quite clear that existing net and boom harbor defenses were inadequate and led to further examination of controlled mines for harbor defense, a tactic previously shunned by the Kriegsmarine in France. Controlled minefields were left inactive to permit friendly vessels to pass, but could be made active in the event of a raid to protect the harbor. The standard types in German service were modifications of existing naval mines such as the RMA, RMB, RMH and KMB but fitted with a remote activation device and tethered by a submarine cable which led back to a mine control station in the port. These mines were eventually deployed in a number of French harbors, but a shortage of mines led to the local development of the so-called Franz WB ( Französische Wasser-Bombe : French depth charge) using captured stocks of French depth charges. These controlled mine units were also responsible for the deployment of harbor demolition mines, which were used in several ports, such as Cherbourg, St. Malo and Brest, to wreck vital equipment prior to the surrender of the ports to the Allies.

Читать дальше