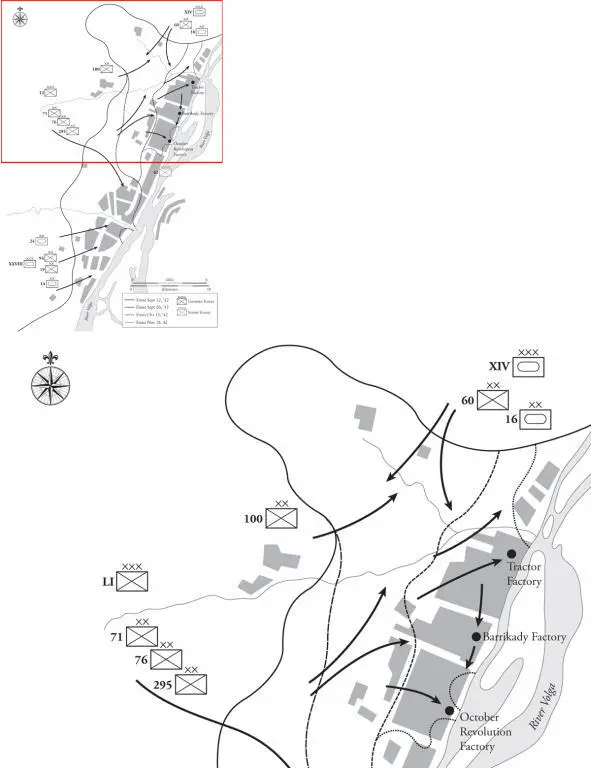

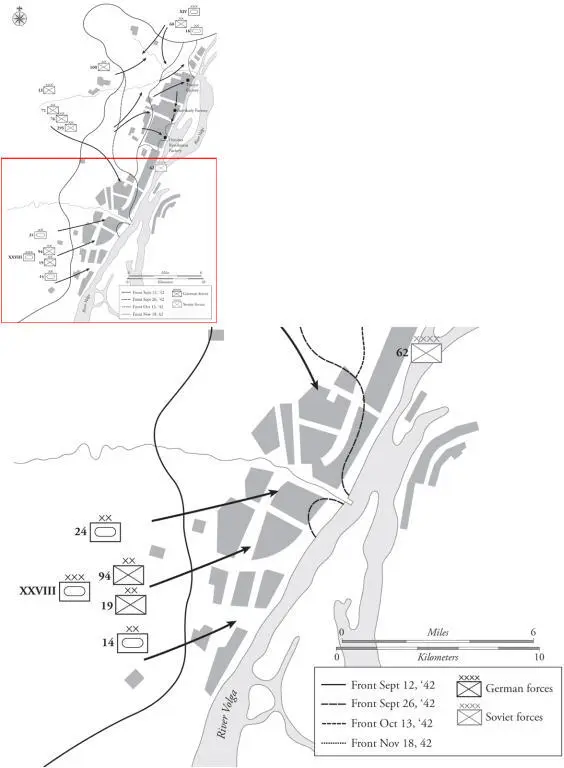

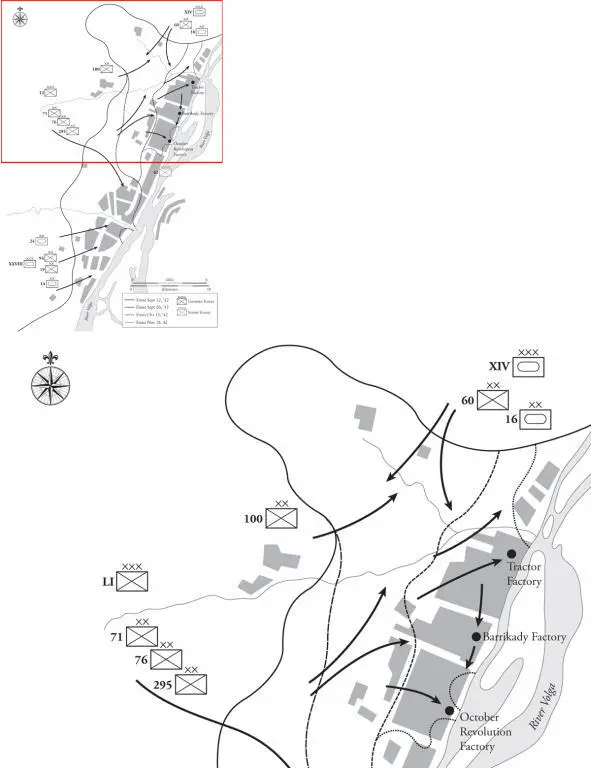

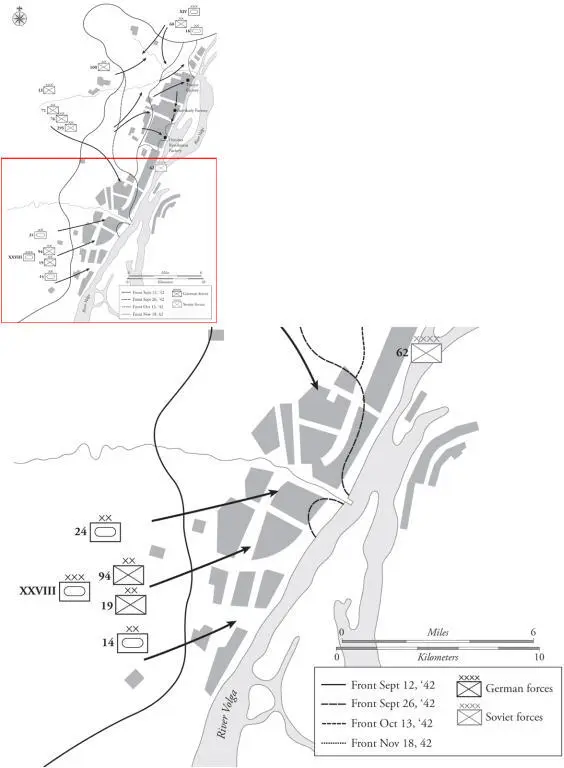

The third major attack to secure the city began on October 14, 1942. Three infantry divisions, two panzer divisions, and five special engineer battalions were committed to the attack — in total over 90,000 men and 300 tanks on a 3-mile front. For another 12 days the Germans ground forward, systematically reducing Russian strongpoint after strongpoint. The Soviets fed additional troops across the Volga but the defenders were running out of space. When the German offensive finally paused on October 27, they held 90 percent of Stalingrad. Only part of the Red October steel factory was outside their control. The Sixty-Second Army was fragmented into small pockets and most of its divisions were completely wiped out. All sectors of the remaining Soviet defenses were subject to German observation and attack. But the German attacks ended without achieving their objective: capture of the city of Stalingrad. As the month came to a close, shortages of troops, ammunition, tanks, and pure exhaustion of the remaining troops made further offensive operations by the Germans impossible.

Winter arrived in Stalingrad on November 9 as temperatures plunged to -18°C. The fighting, however, did not stop. The Germans were no longer capable of large-scale offensive operations but small raids and attacks continued as they attempted to eliminate the remaining Soviet strongpoints. On November 11, battle groups from six German divisions, led by four fresh pioneer battalions, launched the last concerted German effort to secure the city before the coming of winter. It, like all previous German offenses, took ground and punished the Soviet defenders, but ultimately fell short of its objective. In the LI Corps, under General Walther von Seydlitz, 42 percent of all battalions were considered fought-out and across the entire Sixth Army most infantry companies had fewer than 50 men and companies had to be combined in order to create effective units. The 14th and 24th Panzer Divisions both required a complete refitting in order to continue operations in the winter. In short, by mid-November the combat power of the German Sixth Army was almost completely spent after more than two months of intense urban combat.

The German high command, and Hitler in particular, were desperate for a victory at Stalingrad. Desperation does not make for good military decision-making, and over the course of the campaign the German decision-making evolved from taking great risks to simple gambling. By October, the Germans were gambling that the Soviet high command was incapable of simple and obvious military judgment, which was all that was required to recognize early in the battle what an operational opportunity the shaping of the battle could provide to the Soviet high command.

Early in September the senior leadership of the Soviet Union, Premier Joseph Stalin, and generals Aleksandr Vasilevsky and Georgi Zhukov met and identified the operational opportunity that the German disposition at Stalingrad presented. The opportunity was obvious from the map. The Sixth Army was extended deep into Russia at the end of a very long supply line. Long flanks were exposed both north and south of the advance to Stalingrad. An examination of German force distribution reinforced the vulnerabilities of the geometry of the Army Group B front. The vast preponderance of the German combat power, 21 divisions, was concentrated at the very tip of the salient, in Stalingrad. The flanks were comparatively lightly held. Moreover, the bulk of the units holding those flanks were inferior allied units: Italian, Hungarian, and least effective of all, Romanian. These allied formations had been injected into the line in July and August to relieve German formations for employment in Stalingrad. Further exasperating already precarious operational dispositions was the fact that neither Sixth Army nor Army Group B held any significant operational reserves to respond to an emergency. In addition, the units that were best suited to constituting a reserve, the mobile panzer and panzer grenadier divisions, were seriously understrength, short on fuel, and many were decisively engaged in the Stalingrad street fighting and therefore unavailable. The primary Army Group reserve was XLVIII Panzer Corps. The corps consisted of the German 22nd Panzer Division and the Romanian 1st Armored Division. Both units were understrength, and the Romanian division was absolutely no match for Soviet armor. The Germans could not have offered Stalin and Zhukov a more lucrative and tempting target if they had consciously tried to do so.

Through all of September and October the Red Army prepared for Operation Uranus, the counteroffensive against Army Group B. The Russians carefully moved units forward at night to avoid German detection. They used intelligence gathered from captured prisoners and a partisan intelligence network to carefully plot German dispositions. Secrecy was extreme and even senior commanders, such as General Chuikov in Stalingrad, were unaware of the preparations for the counterattack. The German command was the most unaware of what was happening. German intelligence not only was completely unaware of the massive Soviet buildup north and south of Stalingrad, but they were convinced that the Red Army had no significant operational reserves. The performance of German intelligence throughout World War II was consistently poor, and often, as at Stalingrad in November 1942, had disastrous consequences.

In preparation for Operation Uranus, the Soviet Army reorganized its command structure. Three front commands were created in the Stalingrad area. The Southwest Front, under General Nikolai Vatutin, was far to the north and west of Stalingrad. The Don Front, under General Konstantin Rokossovsky was located directly north of Stalingrad. The Stalingrad Front, under General Andrei Yeremenko, had responsibility for Stalingrad itself and units to the south of the city. The plan called for the Southwest and Don fronts to launch attacks deep into the rear of Sixth Army. The Southwest Front’s Fifth Tank Army would attack the Romanian Third Army over 100 miles west of the Sixth Army’s main forces in Stalingrad itself. Simultaneously, the Stalingrad Front would counterattack 50 miles south of the city, aiming at the 51st and 57th Corps of the Romanian Fourth Army.

On the morning of November 19, the attack began. All across the Southwest Front Soviet artillery blasted huge holes in the Romanian lines which were quickly driven through by Russian armor and horse cavalry. The Soviet operational technique was simple: massive artillery bombardment shocked and suppressed the defending Romanian infantry; Soviet armor rolled over the still shocked Romanians who were woefully short of antitank guns and had no armor reserve. Soviet horse cavalry followed closely behind the armor to protect its flanks. Finally, Soviet infantry moved forward and mopped up the remaining isolated Romanian positions. The Soviet assault tactics were extremely effective against the poorly equipped and led Romanians, and Soviet armor formations quickly penetrated and fanned out into the Romanian and German rear areas. The objective of the Southwest Front was the west bank of the Don River and the Sixth Army logistics base at Kalach on the east bank of the Don River. Kalach and the vital bridge over the Don located there were captured on November 22, a mere three days after the attack began.

Map 2.2 The Sixth Army Attack into Stalingrad, September–November 1942

On November 20 the Stalingrad Front launched its attack on the Romanian Fourth Army. The pattern to the northwest was repeated south of Stalingrad. The Romanian forces were quickly overrun by Soviet armor formations which proceeded to advance rapidly against light opposition to the west and northwest. On November 23, four days after the beginning of the offensive, armored forces from the Don Front linked up with forces from the Stalingrad Front just east of Kalach and effected the complete isolation of the Sixth Army and attached troops around Stalingrad.

Читать дальше