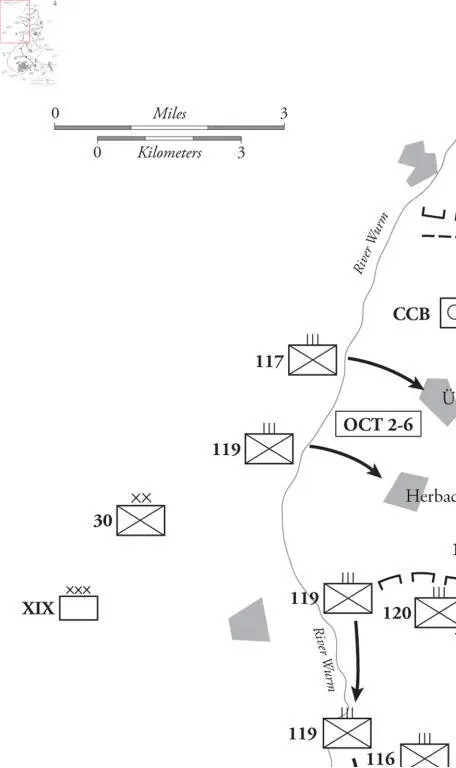

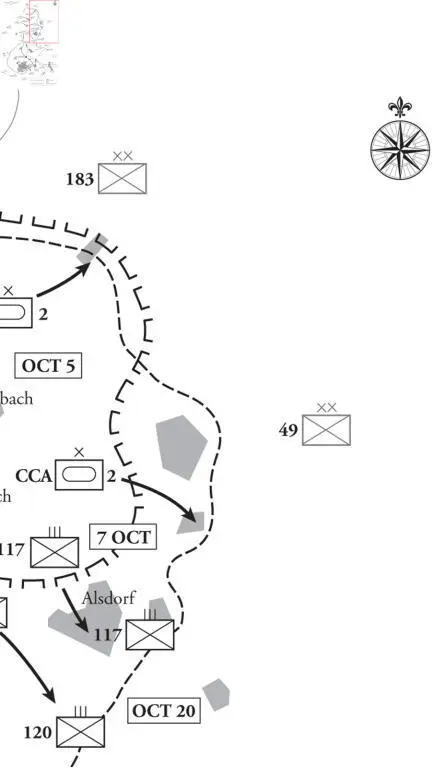

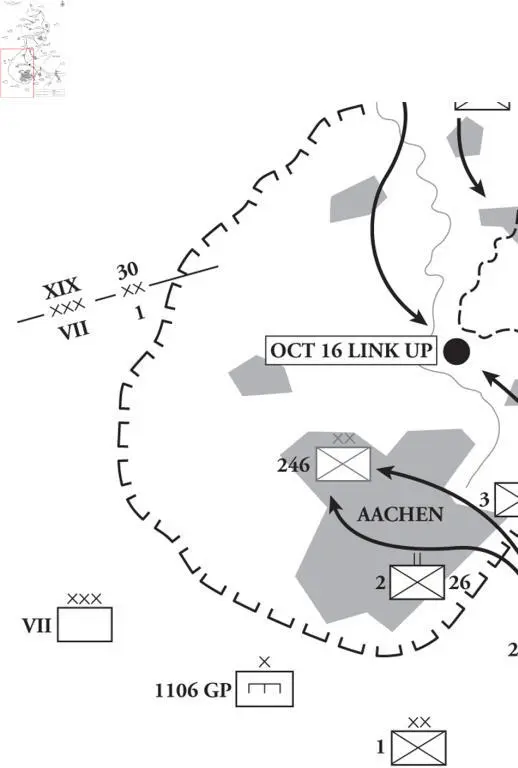

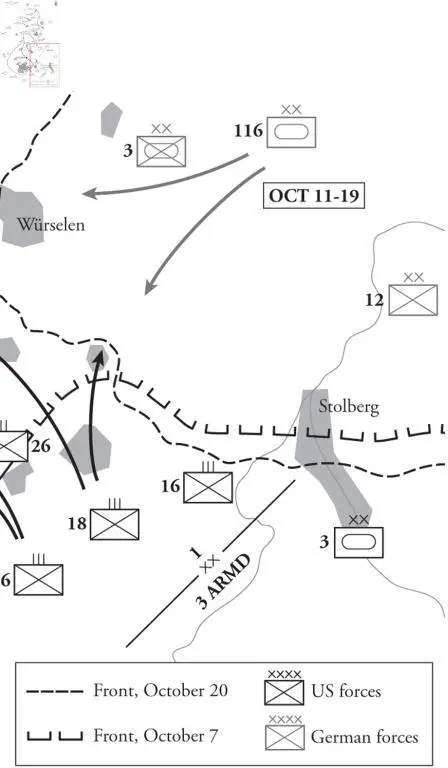

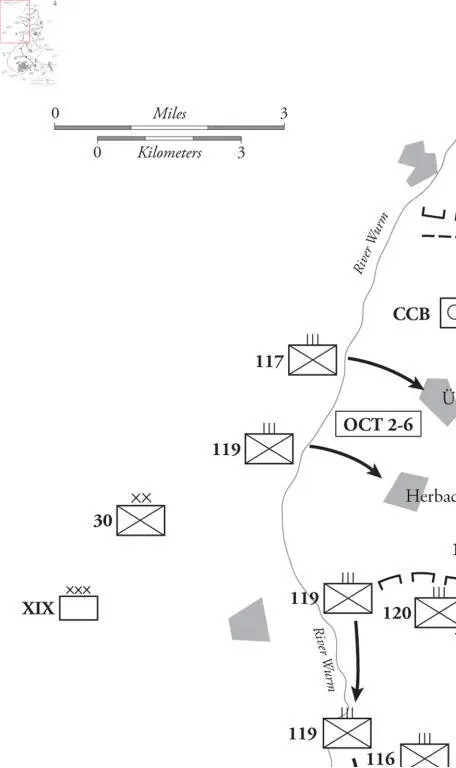

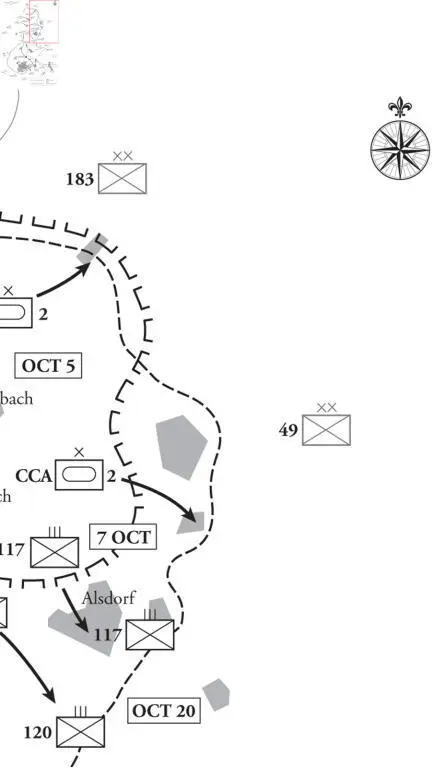

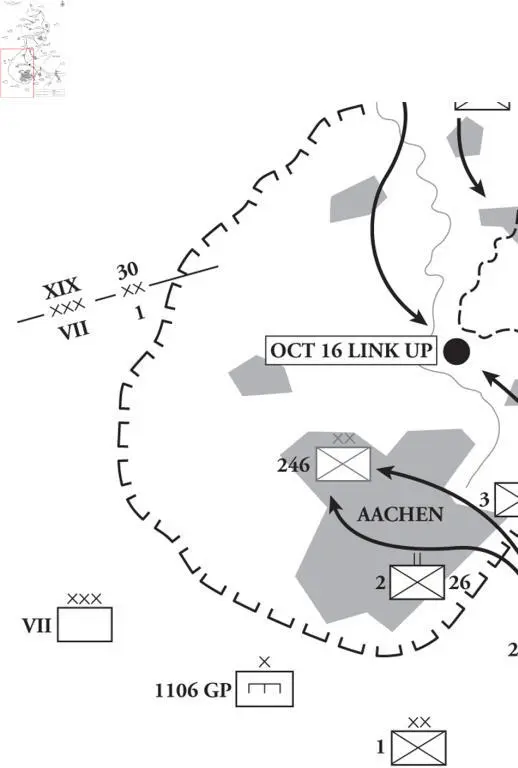

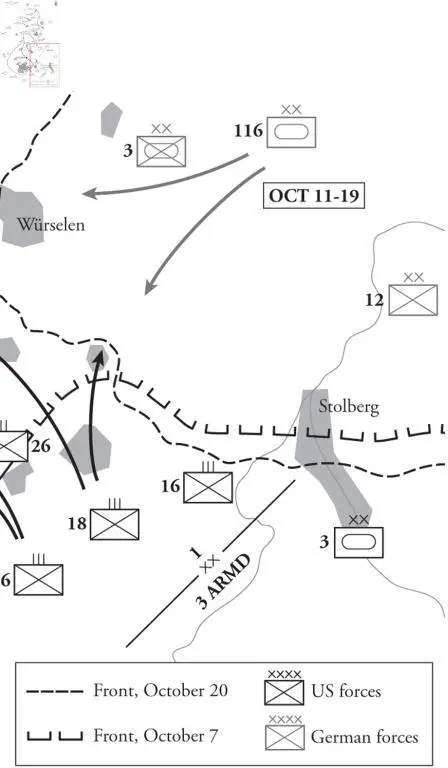

Map 3.1 The Battle for Aachen, October 1944

Meanwhile, the failed German counterattack left the German Seventh Army dangerously exposed to the American armored spearheads spreading out in all directions through the gap in the German lines. In orders reminiscent of Stalingrad, Hitler ordered that the German army not withdraw, and fight for every piece of French soil. This set up the German Seventh Army to be enveloped by elements of the US First and Third Armies which hooked north and east behind the Germans. Simultaneously the British launched an offensive on the opposite side of the front designed to envelop the Seventh Army from the north. As the Allied pincers began to close, the German command recognized the danger and belatedly began to withdraw. Though some of the German Seventh Army escaped the trap at the Falaise pocket, the bulk of it was destroyed and the American and British forces then turned and began to pursue the rapidly retreating Germans toward the German border.

By the middle of September the US Third Army was approaching the German fortress complex in Lorraine centered on the famous city of Metz. The US First Army liberated all of Northern France, Luxembourg, and southern Belgium and was approaching the German frontier defenses, known as the Siegfried Line, along the German–Belgium border. The British 21st Army Group had pursued the Germans north, liberating western Belgium and Antwerp. The British were poised to liberate Holland and cross the Rhine. It was at this point in the offensive, after seven weeks of continuous high-tempo offensive operations, that the bane of all senior commanders — logistics — began to dominate operational decision-making.

Though the breakout from the Normandy beachheads had been wildly successful, the Germans had managed to either defend or destroy virtually all the major port facilities along the French coast. Thus, the two Allied army groups, the 12th US Army Group and the British 21st Army Group, were both primarily reliant on logistics brought over the Normandy beaches. The volume of supplies that the Allies could move over the beaches was limited. Further, the French railroad system had been effectively destroyed by Allied airpower. Thus, most of what was brought ashore was moved forward by truck. There were simply not enough trucks for the job, and thousands of miles traveled quickly began to wear out the trucks that were available. Thus, by mid-September 1944, the Allied spearheads began to grind to a halt for lack of fuel. It was at this time that the leading combat elements of the US First Army reached Aachen, which was virtually undefended.

The supreme Allied commander, General Dwight Eisenhower, was acutely aware of the logistics problems. He also understood that the German army was in full retreat, that the western defenses of Germany were largely unmanned, and that there was an opportunity to possibly end the war before Christmas. Eisenhower had the logistics capability to sustain one of the three major axes being pursued by his armies, but the cost of doing so was stopping the other two offensives in their tracks. For a variety of valid, if arguable, reasons, Eisenhower determined to back his northern attack led by the British Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery’s 21st Army Group. Offensive operations in the US 12th Army Group were suspended and the US First and Third Armies halted. The US forces in the vicinity of Aachen reverted to the defense.

The Aachen terrain corridor was a stretch of relatively open ground that could give large formations access into northern Germany. To the north of the Aachen area was Holland and that approach was characterized by numerous canals, estuaries, associated bridges, and marshes. It was not a promising approach for large mobile formations. South of Aachen lay the Hurtigen and the Ardennes forests. These dense forests lay over steep hills and ravines, had a very limited road network to the east, and thus were excellent for defensive operations and unsuited to large mobile operations. The next eastward avenue suitable for the movement of large mobile formations was far to the south in the Lorraine. It was in this area that Patton’s Third Army operated. Thus, the best approach route into Germany in the northern part of the front was through Aachen, and it was in the northern part of the front that the bulk of the Allied combat power lay.

The Plan to Capture Aachen

Aachen had a special place in German history and in the ideological underpinnings of the Third Reich. Hitler declared the city a “festung” city, a fortress city, and that it was to be defended to the last. Toward this end the Nazi government evacuated most of the citizens as the US forces approached. When the initial impulse toward Aachen in September failed to take the city, the Nazi propaganda machine began to portray Aachen as a reverse Stalingrad. According to Nazi propaganda, the US Army would be lured into a battle for Aachen and destroyed.

The failure of Field Marshal Montgomery’s offensive to cross the Rhine in September — Operation Market Garden — is well documented. Less well known is what German officers on the Western Front came to call “the miracle in the West.” Warfare at all levels, tactical through strategic, is often a matter of simple choices which slow or speed a campaign or battle. Minutes, hours, and days often spell the difference between victory and defeat, or swift victory and slow destruction. The delay caused to the American advance by logistics problems, lasting through the last two weeks of September 1944, was the breathing space that the German command needed to reorganize units, bring forward supplies, and shuffle reinforcements to the west. Thus, at the end of September 1944, when the US armies were ready to resume their advance, they faced a much more formidable foe.

When offensive operations began again on the Western Front in October 1944, not only were the German forces no longer in full retreat, but General Eisenhower had adopted a new strategy for the front. Eisenhower determined that with the failure of Operation Market Garden any single thrust deep into Germany was too risky. Instead he adopted a broad-front strategy. Eisenhower’s concept — to attack simultaneously with all Allied armies from Holland to the Swiss border — was bold and insightful. It leveraged the Allies’ great advantage in resources, and somewhat mitigated any advantage the Germans may have had in tactical skill and equipment. Within the context of this broad-front strategy, General Courtney Hodges planned for his US First Army to resume offensive operations in early October. His initial major objective was the German city of Aachen, which lay on the tri-border point between Holland, Belgium, and Germany. Hodges’ concept was that the Aachen battle would penetrate the Siegfried Line, and open up the Ruhr industrial area to Allied occupation as a prelude to crossing the Rhine River.

The approach to the Aachen, and the battle itself, was controlled directly by the US First Army. This was required because the Aachen sector of the front was split by a corps boundary. The XIX Corps was positioned north of Aachen while the southern portion and the main part of the city were in the zone of the VII Corps. The First Army plan to capture the city was relatively simple. The XIX Corps would attack north of the city and drive east and then southeast to encircle the city from the north. After success in the north, the VII Corps would launch its attack northeast to link up with the XIX Corps. Once the two corps had linked up and isolated the city, elements of VII Corps’ 1st Infantry Division would assault the city directly to capture it.

Читать дальше