Politics and Urban Warfare

One of the major characteristics of the fight for Seoul was the intense pressure put on the Marine division to capture the city quickly. This pressure was resented by the Marine officers because speed often caused them to take risks with the lives of their Marines. Often this was viewed as General MacArthur placing politics before the tactical considerations of urban combat. However, there were good reasons to take the city quickly. First, the military advantages of cutting off the bulk of the KPA south of Seoul were obvious. Second, and perhaps most important, were the psychological and political advantages to be gained by recapturing the city less than three months after its capture by the KPA in June. The capital of Seoul defined the allied government of the Republic of Korea and restoring that city to allied control was extremely important strategically to the prestige and legitimacy of the South Korean government. MacArthur understood how strategic Seoul was to the South Korean government, as well as to the UN cause and to the US home front, which desperately needed positive war news. Thus, like many important capital cities in warfare, the strategic value of the city was worth the tactical sacrifices necessary to capture it, and capture it quickly.

Another characteristic of the battle for Inchon–Seoul was the integration of South Korean forces into the battle. There is no doubt that South Korean forces were not necessary to the battle. However, General MacArthur insisted that the ROK Marine Regiment and the 17th ROKA Infantry Regiment be integrated into operations and participate in the recapture of Seoul. Again, this insistence demonstrated that the fight for a capital city such as Seoul was as much about perceptions and information operations, as it was about tactics. The role of ROK infantry and Marines in the battle was small, but the prestige incurred by the ROK government was huge, and the battle did much to boost the morale and confidence of the ROK military which eventually would assume the largest burden of combat operations in the war and would prove itself capable of fighting not just the KPA, but also the Chinese Army effectively.

A final characteristic of the campaign for Seoul and the battles for Inchon and Seoul was the nature of the assaulting force. The assault force, X Corps, was a unique organization. Though its composition was strongly influenced by the lack of available forces in the early days of the Korean conflict, it was also uniquely tailored to the needs of modern urban combat. The X Corps was a true joint-service force, and a combined allied force, and thus had capabilities not found in a typical army corps. As a joint force it had unique amphibious, naval support, and close air support capabilities which were all critically necessary to the strategic situation, and the tactical problems involved in the recapture of the Korean cities. The leveraging of the capabilities of air and naval power reduced the need for large numbers of infantry, and reduced the casualties among the attacking US and ROK Marines and infantry. The navy ensured strategic surprise and supported the force logistically, and with naval gunfire. The air component augmented artillery fires, protected the force from North Korean airpower, and helped isolate the urban battlefield. Both air and naval forces provided a psychological boost to the assaulting US and ROK Marines and infantry, and demoralized the KPA defenders. As a combined US and ROK force, X Corps represented the unique political nature of the Korean conflict, and maximized the strategic gains that the recapture of the ROK’s capital represented. Neither a single-service corps, nor a completely American corps, could have conducted the operation as effectively, or achieved the same strategic success that the uniquely joint and combined allied X Corps was able to achieve. In many ways X Corps represented an ideal urban fighting organization.

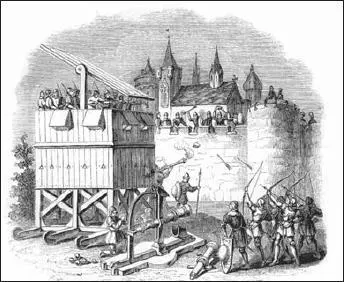

Siege towers were important for the conquering of cities for hundreds of years. They were mobile, provided cover, could be used as a base for fring weapons, and most importantly, allowed the attacker to breach the protective city walls. Soon after the arrival of gunpowder, vertical protective walls and the siege towers used to attack them, became obsolete. (istockphoto)

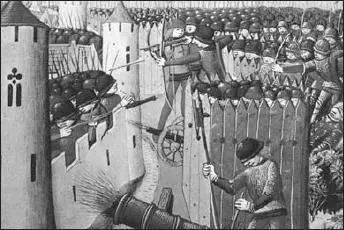

Capturing cities was a major focus of ancient and medieval warfare. The challenge was breaching the city walls — once that occurred the battle was over. However, often the attacker chose to wait and let starvation take its toll on the garrison and population. In those situations the cost in lives of noncombatants would be tremendous. (David Nicolle)

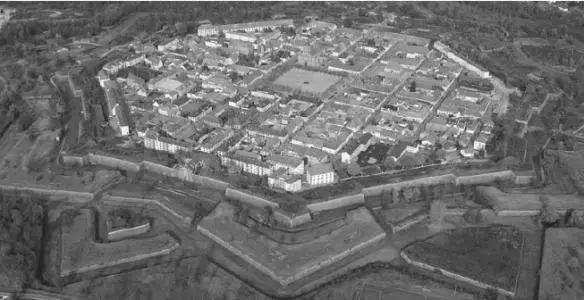

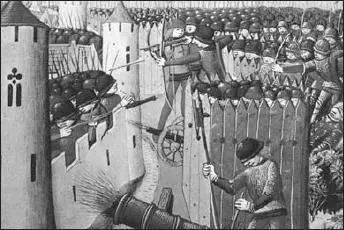

The fortress city of Neuf-Brisach which is a near-perfect example of the early modern “star” fortress. Unlike many such cities, Neuf-Brisach was designed by Vauban in 1698 as a combination fortress and city, with both elements built simultaneously. The fortress city was intended to guard the French border in Alsace. (Getty)

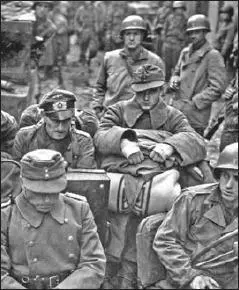

The primary weapon in urban combat: the infantryman. A German infantry corporal in the late summer or early fall of 1942 at the gates of Stalingrad. He is clutching an entrenching tool and wears a black wound badge indicating he has been wounded once or twice. He also wears the infantry assault badge on his pocket indicating participation in three or more infantry combat operations. (Bundesarchiv)

A JU-87 “Stuka” dive-bomber over Stalingrad in the late summer or early fall of 1942. The Germans provided excellent close air support for the Sixth Army during the fall campaign to capture the city. Each German attack was preceded by a Luftwaffe bombardment. This picture also illustrates the width of the Volga river which would have required a major operation on the part of the Germans to cross. The Soviets were able to ferry men and supplies across the Volga and into the city throughout the entire campaign. (Bundesarchiv)

German infantry captain observing the Stalingrad battlefield in October 1942 from a position near the ruins of the Barrikady weapons factory. He is armed with a captured Soviet PPSh sub-machine gun. Sub-machine guns were ideal for urban fighting where engagement ranges were short, numerous targets appeared in a small area, and space for aiming and firing a weapon could be tight. (Bundesarchiv)

German infantrymen dug into a fighting position. The infantryman in the foreground is armed with the standard German infantry rifle of World War II, the 7.62mm Kar98k. The German position is built next to a knocked-out Soviet T-34 tank. (Bundesarchiv)

German infantry preparing for one of the last assaults to clear the Soviet Army from the west bank of the Volga in late fall 1942. For the infantry, Stalingrad was an unrelenting battle with no respite. The exhaustion caused by intense urban combat is evident on the faces of these men as they ready themselves to attack once again. (Bundesarchiv)

A Sturmgeschütz IIIa (StuG IIIa) maneuvers through the dust of Stalingrad in September 1942. The Sturmgeschütz III was a tracked infantry support vehicle, not a tank, and specifically designed to assist infantry reduce fortifications. It did not have a turret but had very thick frontal armor and was ideal for urban warfare. (Bundesarchiv)

Russian aerial bombs loaded on a rail car outside Stalingrad’s tank factory in November 1942. The tank factory was one of several large industrial complexes big enough that armored vehicles could fight inside the building. (Bundesarchiv)

A StuG IIIa carrying infantry to battle in Stalingrad, October 1942. The StuG IIIs were not part of the panzer corps but rather part of the German artillery corps because of their unique role of directly supporting the infantry. As evidenced in this scene, two months into the battle the city infrastructure was essentially destroyed. (Bundesarchiv)

Panzerkampfwagen IIIj (PzKpfw IIIj) of the 24th Panzer Division during the march to Stalingrad in the summer of 1942. The track draped across the front is intended to add some additional armor protection. The PzKpfw III was notoriously outgunned and less armored than its Soviet counterparts, but it still was a formidable opponent due to superior command and crew abilities. Most of the Sixth Army’s tanks were committed to the city fighting in Stalingrad when the Soviets launched their powerful counterattack in November and the 24th Panzer Division was caught in the surrounded city. (Bundesarchiv)

Sherman tanks move carefully through a town near Aachen. In addition to its firepower, the tank, when working in close coordination with infantry, could provide mobile cover from small-arms fire and allow infantry to close on a building. (NARA)

Field Marshal Walter Model, commander of Army Group B which included the Aachen area. Known as “Hitler’s fireman” for his ability to save desperate situations, he gave Aachen high priority and committed some of the best German units available to its defense. (Bundesarchiv)

Colonel Gerhardt Wilck (front left), commander of the 246th Volksgrenadier Division and the Aachen garrison. He had very specific orders from Hitler to defend the city to the last man and if necessary allow himself to be buried under its ruins. (NARA)

The Americans reorganized their infantry companies as assault units by attaching special equipment, engineers, and tanks to the companies. These were then divided amongst the platoons, making each platoon an individual assault team. Machine guns covered the streets while infantry moved through the building interiors as much as possible. (US Army)

Sherman tanks of the 743rd Tank Battalion support the 30th Division as it attacks to isolate Aachen. Though the Sherman tank was not the best tank of the war, in urban operations any armored vehicle is a critical asset to the attacking force. (NARA)

An M12 155mm Gun Motor Carriage (self-propelled gun) in action in Aachen. Tank guns and ammunition were not always sufficiently powerful to have great effects on the concrete and stone buildings of Aachen. Although primarily designed as an indirect-fire artillery weapon, M12s were specifically requested by the 1st Infantry Division for direct-fire support against buildings and bunkers. The powerful gun could bring down an entire building with one shot. (NARA)

A 57mm antitank gun fires on German defenses. The 57mm guns were somewhat effective at suppressing German defenders in buildings, allowing infantry to close in and assault the position. (NARA)

A 3in. antitank gun of the 823rd Tank Destroyer Battalion establishes a position outside Aachen to guard against German armor. The Germans committed a significant amount of armor, including King Tiger tanks, in counterattacks to attempt to keep access to Aachen open. (NARA)

An M-4 tank of the 745th Tank Battalion in Aachen. Tanks operating in Aachen had to be very careful not to remain exposed on the open street for too long and not to get separated from the infantry they were working with. The German Panzerfaust anti-armor weapon was widely distributed among German infantry, easy to use, and deadly to the Sherman tank. (NARA)

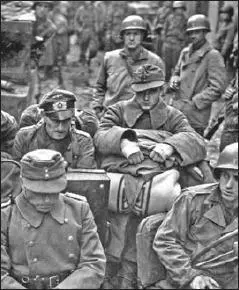

German prisoners marching into captivity. Over 3,000 prisoners were captured in the main part of Aachen, which was attacked by two battalions of the 26th Infantry Regiment. (NARA)

US Marine Corps F4U-5 Corsair of VMF-312. The 1st Marine Division’s air wing gave them and the entire X Corps great flexibility in supporting the attack into Seoul. When the corsairs moved to Kimpo airfield it was possible for pilots to drive by jeep and visit the forward regiments and then return to the airfield to fly missions the same day. (USMC)

Marines of the 1st Battalion, 5th Marines scale the seawall on the northern side of Red Beach, as the second assault wave lands at Inchon, September 15, 1950. Wooden scaling ladders are in use to facilitate disembarkation from the landing craft. (USMC)

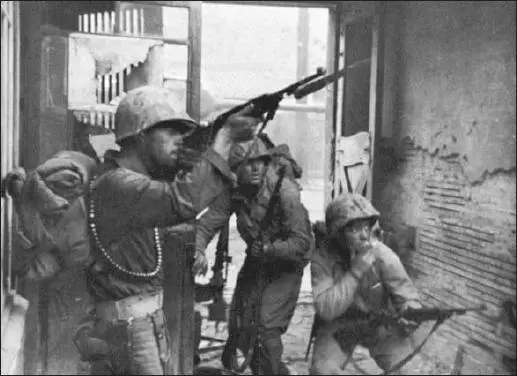

A Marine squad on the approach to Seoul. Dispersal was essential because, though the main North Korean defensive position could be easily spotted, hidden snipers were a constant threat. (USMC)

A Marine squad, supported by an M-26 General Pershing tank of the 1st Marine Tank Battalion, moves through Seoul under fire. (USMC)

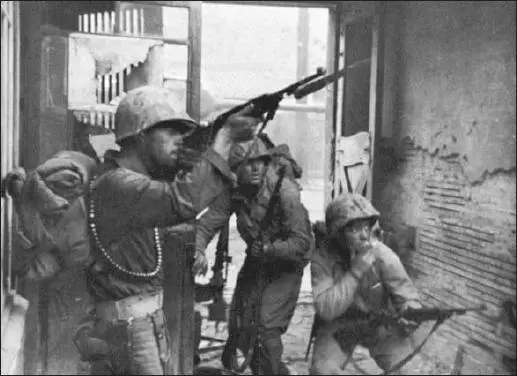

A Marine squad in Seoul suppresses sniper fire with small arms. The Marines are armed with M1 carbines and the M1 Garrand semi-automatic rifle. Outside the building in the background, is a Marine M-26 tank. (US Army)

Marines evacuate a wounded comrade down a street in Seoul. (USMC)

A Marine raises the American flag above the US consulate in Seoul, September 27, 1950. (Getty)

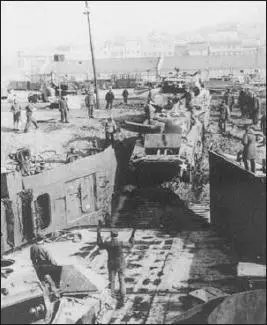

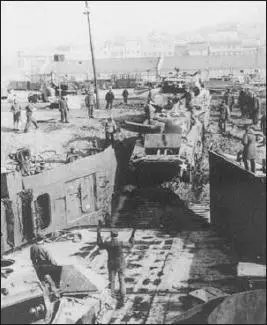

A US M-4 Sherman tank pushes another Sherman tank onto a Landing Ship Tank (LST) at Inchon for evacuation to Japan and repair. In the Marine 1st Tank Battalion, Sherman tanks were used as flamethrower tanks and as dozer tanks because those capabilities had not yet been adapted to the M-26. (US Navy)

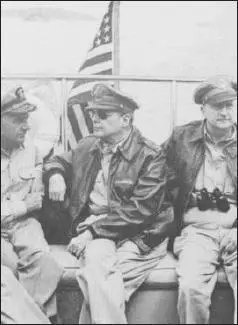

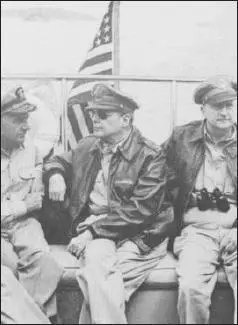

US Army General Douglas MacArthur (center) conceived and supervised the Inchon-Seoul campaign. Many analysts believe it was his finest operation. He clearly understood the important political symbolism of recapturing Seoul. (US Navy)

A USMC M-48 tank supporting the 1st Battalion, 5th Marines, in the battle for the citadel in Northern Hue. (USMC)

USMC M-48 tank overlooking the Highway One bridge over the Phu Cam Canal. The PAVN destroyed the bridge late in the battle, too late to stop USMC reinforcements moving into the southern part of the city. (USMC)

Marine riflemen, armed with M-16 assault rifles, establish a second-floor position overwatching a walled garden in Hue. (USMC)

A Marine Ontos crewman lays exhausted across the front of his vehicle. The 106mm recoilless rifle, six of which were mounted on the Ontos’ lightly armored frame, was the perfect weapon for punching holes in the sides of Hue’s concrete buildings. The dust cloud raised by firing the weapon also provided concealment as the Marines rushed across streets to assault buildings. (NARA)

Читать дальше