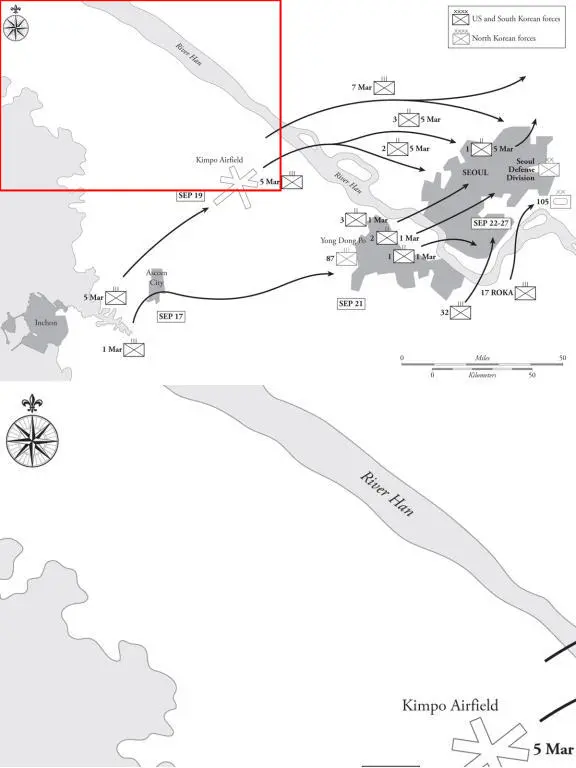

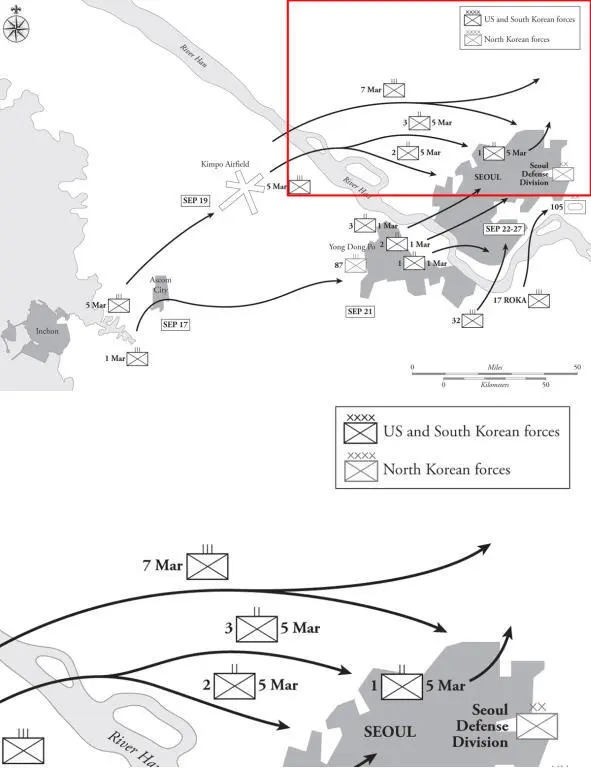

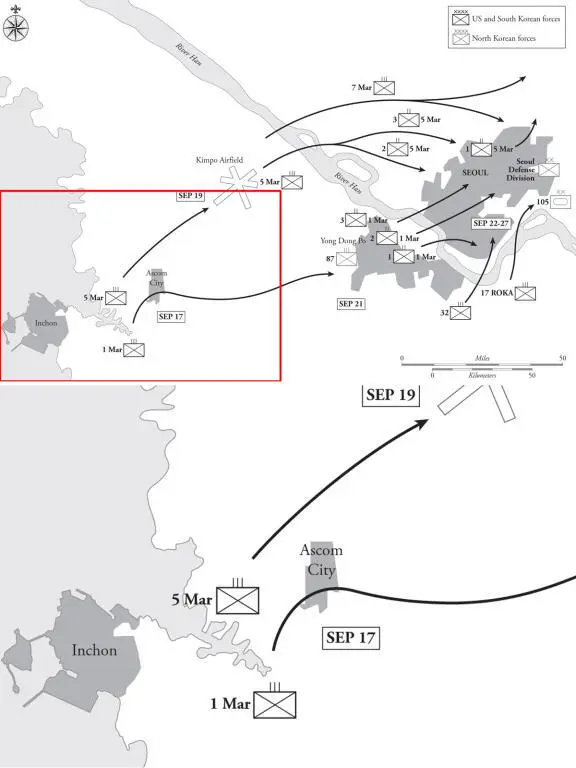

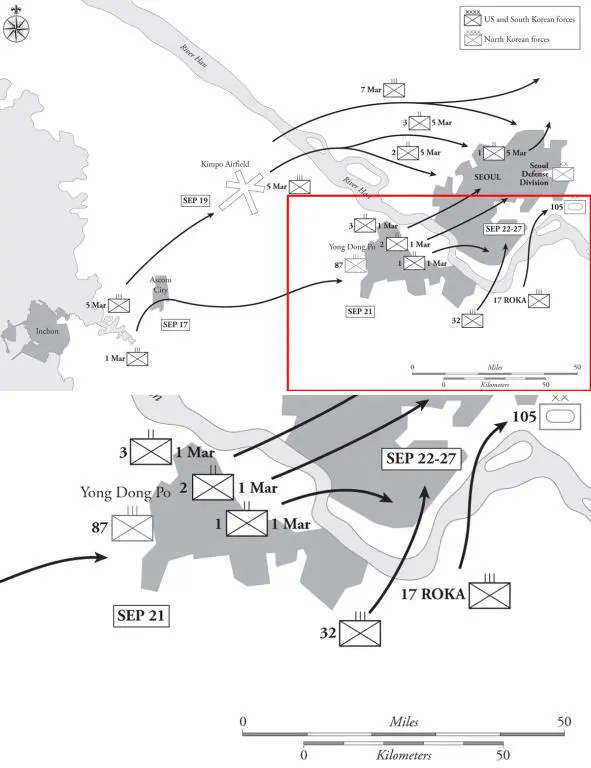

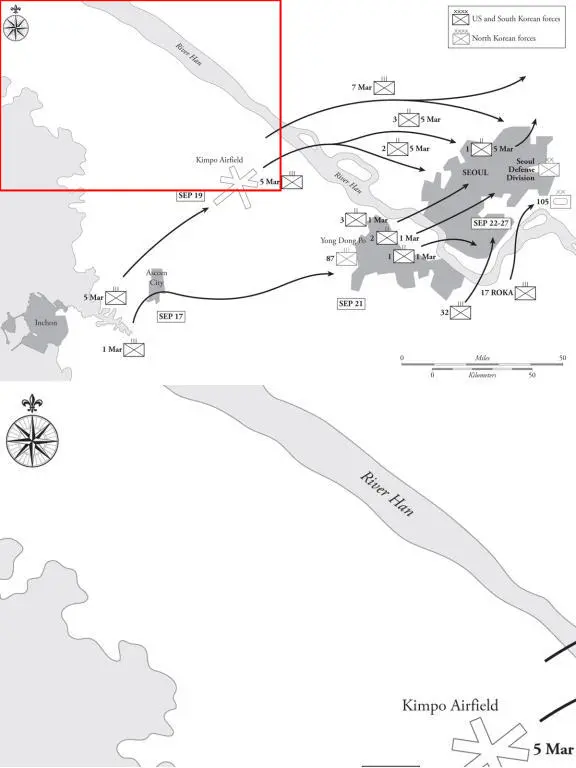

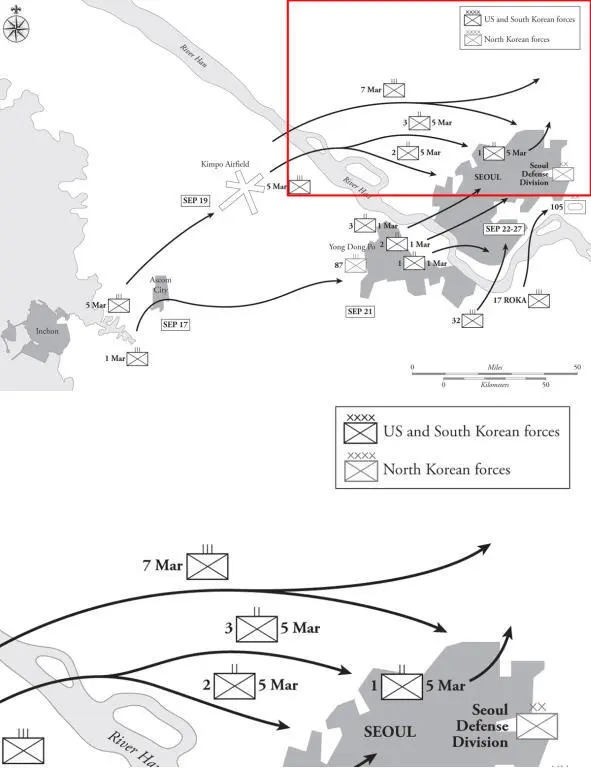

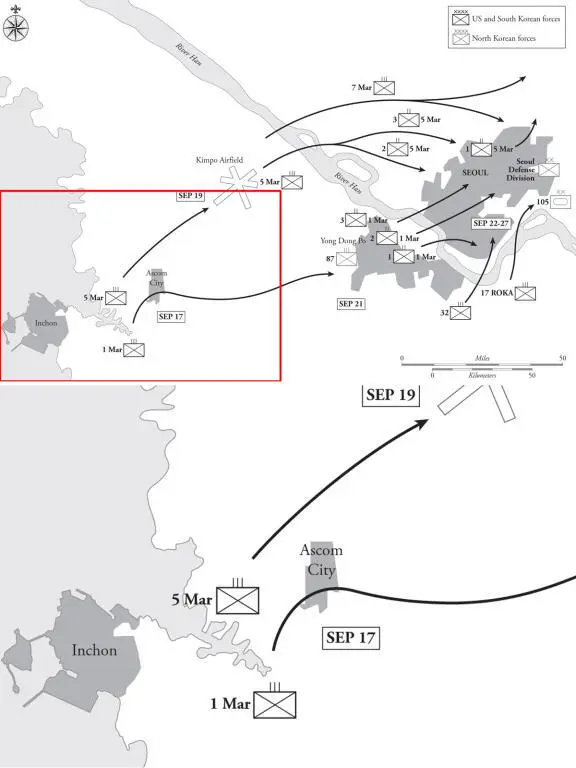

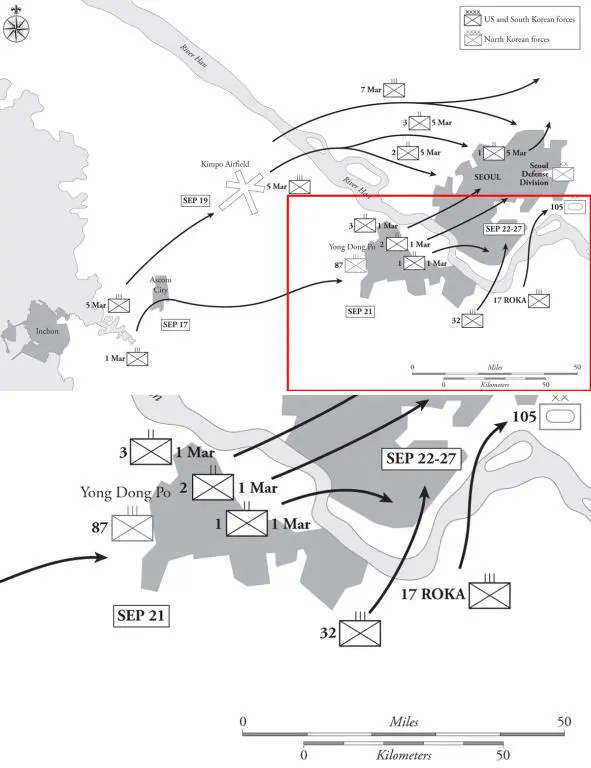

Map 4.2 The Capture of Seoul, September 1950

On September 29, 1950, General Douglas MacArthur and South Korean president, Syngman Rhee, arrived in the capital and General MacArthur declared the city secure. In fact, significant fighting continued as the American units in the city, aided by South Korean forces, continued to systematically clear buildings and streets. Nonetheless, the city was declared secured exactly 90 days after the outbreak of hostilities. The major portion of the 1st Marine Division moved to the eastern portion of the city and prepared to pursue the North Korean army north. Earlier, on September 26, at Suwon, 30 miles south of Seoul, elements of the US Eighth Army linked up with X Corps’ 7th Infantry Division. Between Seoul and Pusan, the North Korean army was completely shattered.

Large urban areas are very difficult objectives to seize except at great cost both in resources and time. The key to the successful capture of a large city, quickly and with minimum expenditure of resources, is to seize it before it is adequately defended. This is extremely difficult to do and can only be accomplished through one of three types of operations: airborne assault; amphibious attack; or a deep rapid armored thrust. General MacArthur recognized that a counteroffensive launched from the Pusan perimeter alone would likely devolve into a long and costly battle of attrition through the Korean mountains, and through numerous large urban areas, including Seoul. The Inchon landing operation, at some significant risk, avoided a war of attrition and resulted in the fall of Seoul in just over 10 days with minimum losses. Unlike most World War II urban battles, the battle for Inchon and Seoul was a battle of maneuver. This was primarily because the attacking force was able to achieve strategic surprise and thus the defender did not have the time to assemble forces and could not establish a comprehensive defense of the entire city area.

The US Marine approach to urban warfare in Seoul was relatively straightforward. Seoul was a huge city which, with Yongdungpo, covered about 80km 2(30 square miles). Despite having more than 20,000 troops available, the North Korean Army had insufficient manpower to defend a continuous line of buildings. The North Korean forces in the city choose to defend fortified barricades oriented on the major avenues and significant natural and city terrain features. The fight for the city became known as the battle of the barricades. Along the city streets the North Korean army erected barricades, constructed of whatever material the North Koreans could find within the city. This included rubble and dirt-packed rice bags, bricks, household furniture, old cars and buses, and any other obstacle-making device they could find. These were torn down by the US and ROK infantry and engineers, or driven over by US tanks. The Marines developed a standard approach to the barricades: artillery fire on the area followed by mortar fire on the position; machine-gun and bazooka fire to suppress the enemy while engineers cleared mines; and finally with the mines removed, the tanks moved forward. The powerful US M-26 tanks were often able to simply plow through the assorted debris. With the tanks came the Marine infantry armed with semiautomatic rifles, fixed bayonets, and grenades. Marine scout-sniper teams overwatched all operations and took a deadly toll on any enemy not behind cover. Each barricade was stoutly defended by North Korean infantry supported by antitank guns, machine guns, and snipers; and took about 45 to 60 minutes to reduce. Thus the movement through the metropolis was of necessity slow, but steady.

A potentially major threat to the US operation was the Soviet-built T-34/85 tanks of the North Korean People’s Army 105th Tank Division. In the march from Inchon to Seoul, 53 of these lethal machines were thrown into counterattacks against the Marines. These tanks had been extremely effective combat vehicles against the best German armor in World War II just five years before. They also furthered their reputation in the first weeks of the North Korean invasion. However, after the initial encounter, the Marines were completely nonplussed by their arrival on the battlefield. They were easily destroyed by a combination of Marine close air support, Marine M-26 tanks, and antitank weapons. By the time the Marines secured the west bank of the Han River, 48 had been knocked out by the Marines and five were found abandoned. In the battle for Seoul itself, the 1st Tank Battalion destroyed 13 T-34 tanks or Soviet-built self-propelled guns and 56 antitank guns, for the loss of five Pershing tanks and two Shermans (most of the American tank losses were to mines and at least one was lost to one of the frequent attacks by North Korean sappers armed with satchels of explosives). Importantly, North Korean armor was of sufficient strength that it could have completely disrupted the US operation, had the US not enjoyed close air and armor support. Thus, armor and close air support were again proven to be very important factors to successful urban combat.

The relatively small size of the US attacking force was possible due to effective air, naval, armor, and artillery support. The air support of the Marines in the Inchon-Seoul operation was particularly effective and noteworthy. Marine aviation units perfected the art of close air support during the Korean War, beginning in the Inchon–Seoul battles. That support was far more responsive and closely coordinated than that achieved by the Marines in World War II. Six Marine squadrons (four day-fighter and two night-fighters) supported the 1st Marine Division and X Corps during the operation. They were controlled by the 1st Division’s 1st Marine Air Wing. They had no other mission other than close air support of the ground forces. Initially the Marines flew in support from two navy escort carriers, the USS Badoeng Strait and the USS Sicily, but once Kimpo airfield was captured, the five F4U Corsair squadrons and the one F7F Tigercat squadron operated from that base, literally minutes from their targets. Close air support was coordinated by Marine Tactical Air Control Squadron 2, which commanded tactical air control parties (TACP) located in each Marine infantry regiment and battalion headquarters. When the US Army 32nd Infantry Regiment entered the battle for Seoul, a Marine TACP was attached to the regiment to give it the benefit of close air support. During the 33-day campaign, September 7–October 9, the Marine aviation units flew almost 3,000 ground-support sorties, including over a thousand in support of the Army’s 7th Division.

Aviation support was critical to the advance from Inchon to Seoul. It was particularly critical to the 5th RCT’s difficult attack south on the east side of the Han River. However, once units entered the city proper the use of close air support became increasingly difficult because of the difficulty of identifying the front line from the air and the danger to the friendly civilian population. Still, even as the battle raged inside Seoul, close air support played an important role aiding the advance of the 7th Marine Regiment through the mountains north of Seoul, isolating the city from reinforcements, and destroying KPA units attempting to retreat from the city.

Читать дальше