“Is this your first child?”

“I had a stillbirth last year,” I said.

“I’m so sorry,” she said immediately, words I’ve never tired of hearing. We went over the details a little, and then she said, “You’ve scheduled an amnio.”

“Yes,” I said. In France the blond Baltimorean asked us if we were worriers; when we said yes, she made an appointment for an amniocentesis. Even so, I’d been startled when I spoke to the French genetic counselor, who was heavily pregnant herself, and she informed me that if the results came back positive for Down syndrome, they “recommended” that we terminate the pregnancy. Edward and I hadn’t discussed what we’d do if it turned out that Pudding had Down syndrome, because we agreed that all the theorizing in the world would probably crumble to dust in the face of a fact.

But this time it was different. We simply wanted to know. It would only be information.

“I mean,” I said to Dr. Knoeller, “we figured we might as well. I guess. I don’t know. What do you think?”

Well, she said, the real question was, if we had an amnio, and the results were normal, but it was one of the one in two hundred pregnancies that miscarried after the procedure, how would we feel?

We were stunned into silence, because of course that was the question. Even if you rephrased it — as Edward pointed out, one in two hundred sounds worse than one half of one percent because with the former you visualize actual people — we weren’t willing to risk it. Once you’ve been on the losing side of great odds, you never find statistics comforting again.

She said in a manner both businesslike and warm, “Let me just say that I had an amnio myself, but I didn’t have your history.”

And just like that, our history was in the room, and I had found a doctor I loved.

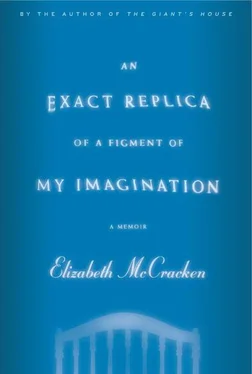

Another woman might want a doctor who promised things: an optimist, a dreamer. Not me. I wanted exact realism and no promises. On one visit a nurse spoke of the kid as though he or she was a foregone conclusion, and I hated it, I wanted to correct her, I wanted to point out that I’d thought that once, and look what happened.

“Well, very good,” Dr. Knoeller said at the end of every visit. “So far, so good. Let’s hope it continues that way.”

And then I was twenty-eight weeks pregnant, and when Dr. Knoeller walked into the room, I swore you could see Walt Disney bluebirds toying with her stethoscope and bunnies congregating around her heels.

“Twenty-eight weeks!” she said. “Now we can relax.”

For my first pregnancy I couldn’t imagine not finding out the baby’s gender. I’d asked Lib why she’d allowed her two daughters to keep their mystery in utero, and she said, “I didn’t want to project who I thought they’d be. I wanted them to be themselves.”

This is exactly the kind of thoughtful and maternal answer I’d expected from Lib. Me, I wanted to project. I was impatient to make up stories about whoever Pudding was, kicking about in my midsection, but how could I without that essential piece of information? For our second child we decided to do everything differently — no amnio, no peeking during ultrasounds. Now and then I wondered whether that was wise: should something happen (it won’t!), should the worst happen (it’s not impossible!), wouldn’t we rather know? It’s terrible to miss Pudding, of course, no matter what, but — this is a total illusion, I understand, nothing but the sentimentality of expectant parents spinning fairy tales ahead of time, viewed in the rearview mirror — it feels like we knew him. I can’t wrap my brain around losing a child and learning only then whether you’d lost a son or a daughter. Not finding out felt like an odd form of optimism.

By the end of my first pregnancy I’d felt very tender toward Pudding — to my made-up companionable Pudding, an infant who would of course love us the minute he saw us, who loved us already, who contained within him not only infancy but babyhood and toddlerhood, who already listened to our voices, who was impatient to meet us (so why was he taking his time?). I stroked my stomach and told him stories; when he kicked, I poked him back. We went to the pool together, me swimming in the chlorinated municipal water of Bergerac, he swimming inside me, both incredulous at how the French could gossip while doing the backstroke. We went to the gym together, where the French not only gossiped and kissed each other in the squat rack, but tucked their shirts into their exercise pants. I ate so that he could eat: I announced what was on the menu.

You don’t need much to hang a personality on someone you haven’t met: a name, some knowledge of the parents, a gender. You can spin anything you want out of those things.

But it wasn’t all so easy. Every now and then, like any pregnant woman, I would panic. When did I last feel this baby move? Then I would lie on the sofa, and put my hands on my stomach, and wait to feel a kick, and then another. Both Dr. Baltimore and Dr. Bergerac had sonograms in their offices, and so for the first six months we saw Pudding on the Big Screen every month. Yes, I did worry, sometimes.

But mostly I didn’t.

This is one of the most painful things for me to remember. I was smug. I felt sorry for women with complicated pregnancies and gloated that I wasn’t one of them. I believed that the pregnancy would continue to be a delight. I imagined that traveling with him afterward, at four weeks old, to England and then to America, would be only an adventure, a story I would tell him for the rest of his life.

I believed he was perfect.

I don’t know whether my faith is explained by hormones or misplaced trust in medical science. I just believed he was perfect. I believed I understood him.

Of course that wasn’t true of my second pregnancy, when I was certain every other moment that something was going terribly wrong. I was neurotic about food; I washed my hands like an insane person. Among my many worries was that I would feel unconnected to this second occupant and that this indifference would travel through the placenta and warp the developing psyche. But I turned out to feel another sort of closeness. Pregnant with Pudding, I often didn’t even realize how big I’d gotten; we communicated via dream telegraph. During my second pregnancy, I was by necessity obsessed with the physical, and this baby — who was in there, anyhow? — was a great in utero kicker and squirmer. Once the kid was big enough for me to feel, I would think once a day, panicked, When’s the last time I felt the baby move? And then I’d palm my stomach. Thump, thump, thump. What a good baby, what a wonderful obliging baby, was there something wrong with that baby, to make it shift so? Was that a kick or a shudder or head banging? You couldn’t deny it: there was a baby in there. Even so, I sometimes wondered whether I was making it up.

“Shh,” I’d say to my stomach, “you’re all right,” and to Edward, “Who’s in there, do you think? It could be anyone .”

“Not anyone, ” he’d say, looking a little troubled.

I taught my classes and grew subtly stouter but said nothing. It seemed as though something terrible would happen if people knew. By which I mean: not that we would be tempting fate, but that I would have to acknowledge that the pregnancy was real, and if I did that, I was sure, I would take to my bed until spring. I told a handful of friends in October, and a handful of relatives at Thanksgiving.

Lib insisted I was having a girl. Edward, who had correctly and with great certainty predicted Pudding’s gender, agreed. I had no idea. When I was four months in, Ann declared, no room for argument, that I was pregnant with a boy, and listen: her husband’s daughter was pregnant, too, and Ann had said Josephine was going to have a boy, and the first ultrasound had the temerity to disagree with Ann’s prediction, but Ann wouldn’t budge, and then the second ultrasound said, All right, yes, a boy.

Читать дальше