So I don’t really understand why we need a car. To get to Havsbadet, we walk or cycle. To get to work, the two of you take your bicycles or the branch line. Going to Stockholm or Borås we take the train, as I’ve explained. Cars aren’t very common on the rowanberry avenue. Anders’s dad has a car that’s usually parked in the yard outside the house and sometimes needs to be cranked up with a large handle, but then Anders’s dad has a store in the main square selling spare parts and maybe that’s why he needs a car.

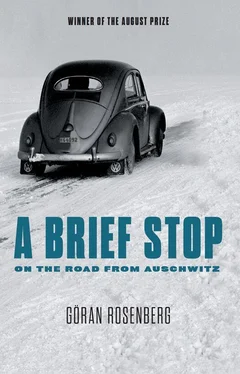

Our car’s a 1955 black Volkswagen, registration number B 40011, and it’s the latest model, with a small back window and semaphore arms for directional signaling. Anders keeps going on about the Beetle’s having its engine at the back and being cooled by air, whereas his dad’s car and all other cars have the engine in the front and are water-cooled. It’s safer to have the engine at the front and the petrol tank at the back, Anders says, but I’m not interested in the difference. Nor am I particularly interested in the car as such. One hot summer day, it just happens to be there. I remember that whole summer as very hot and very nice, and we use the car for day trips on holidays and Sundays. A car isn’t for going from one place to another, but for going nowhere in particular to unpack a picnic basket or a deck chair, or just see the world through the car window. A car ad in the local paper reads “Everything’s so much easier now. On Sundays and work-free days we can get out into the countryside, go for a dip, pick berries and mushrooms — or just take a spin. Try a Volkswagen for that wonderful feeling of independence.”

We take the car to Lake Malmsjön instead of walking or biking to Havsbadet. We take the car in the summer when Aunt Bluma and my cousins from Tel Aviv stay with us in the small two-room apartment on the other side of the rowanberry avenue. We take the car to Karin and Ingvar’s self-built little country cottage. We take the car to Stockholm now and then, even though the train is quicker. We never take the car to Borås. When the car’s full of people, I squeeze into the little space between the back seat and the engine compartment. The roads are narrow and winding, and the wind rushes noisily through the open windows, and the engine whines through the compartment wall, and it’s tiring to travel by car. Lots of people on the rowanberry avenue spend their Sundays and work-free days washing and waxing their cars until they shine like new.

The simple truth is that a car is a luxury, just yesterday unthinkable for a pipe fitter at Scania-Vabis and a seamstress at Tornvall’s, but in the new life in the new world, so many things that were unthinkable only yesterday are not anymore.

The car becomes a part of the Project in the same way as the plans for a self-built house in Vibergen and citizenship.

On May 7, 1954, the two of you become Swedish citizens.

The clearest indication that I overestimate the Place’s importance to the Project is that for quite some time, you continue to consider leaving it and moving on. Many of the people who contribute to the confusion of languages around our blanket on the sands of Havsbadet in the first years do what the express trains do, they make only a brief stop and then move on. Some cross the bridge to Stockholm once that route is opened to them, but most move on to begin their lives anew in another world. The other worlds are called Israel and America, Jisroel unt Amejrika . The Wyszogrodzki family, who live in the apartment block opposite ours on the rowanberry avenue, move on to Israel, where one no longer has to travel illegally by freighter. Moniek Wyszogrodzki is a pastry cook and a racing cyclist and my godfather. In Jewish tradition, the duty of the godfather or sandak is to hold the child’s head at the circumcision ceremony, which takes place when I am eight days old. My image of Moniek Wyszogrodzki is formed much later, when he’s a pastry cook and a racing cyclist in Israel, living with Mania and four daughters in a lovely house on the slopes of Mount Carmel, looking out over Haifa Bay and the gold-glittering Bahá′i Shrine. Moniek, now Moshe, Wyszogrodzki has red hair, a freckled face, and gray-blue eyes that radiate the energy and will of a competitive personality. Mania bears the physical marks of the road to and from Auschwitz, a lined face and gaps in her teeth, but not Moshe. Moshe lives by the cycling theorem: if you don’t keep pedaling, you fall off. In Södertälje, he’s a member of the Amateur Cycling Club.

Much later I realize that some of his energy and will also benefits you. Besides holding my head steady during circumcision, he also has a hand in the housing miracle, the little one-room apartment with the window facing the railroad tracks in the house across from the bakery.

It doesn’t surprise me that the Wyszogrodzki family’s departure from Södertälje prompts an article in the local paper. It’s December 17, 1949, and the article makes the front page, and it’s the result of Moniek Wyszogrodzki energetically and on his own initiative striding into the newspaper office and requesting to express, through the paper, “his gratitude to Södertälje for the hospitality he and members of his family have enjoyed.” In particular he wants to thank his friends in the Amateur Cycling Club. The article reveals that the Wyszogrodzki family has already departed by train for Malmö, from where they will fly to Marseille and continue to Haifa by boat, and that they have left Södertälje together with “the tailor Adam Glusman [sic] and his wife Polla.” It’s obvious from the article that the writer has difficulties in fully comprehending Moniek Wyszogrodzki’s story about his road to Södertälje, and I don’t think it’s due to a confusion of languages. I rather think it’s a certain rigidity inherent in the journalistic language of the day that manifests itself here. In any event, it’s a contemporary historical document, and I’ll let it speak for itself:

We both came from Germany in 1945 after having spent a rather long time in concentration camps. We didn’t arrive here together, but by sheer chance happened across each other in Karlstad in December 1945. We hadn’t seen each other for five years. It goes without saying that we were happy to see each other.

Sadly, my wife had contracted TB in the difficult years in Germany and had to spend two and a half years in various sanatoriums. Fortunately enough, she has made a complete recovery.

This is the only article I can find in the local paper about the temporary community of survivors in Södertälje, apart from the one about the confusion of languages on the sands of Havsbadet. Within a few years, virtually the whole community has moved on. The majority are women from Bergen-Belsen or Ravensbrück, who have come to Södertälje to make clothes at the Tornvall garment factory, where the yearly staff turnover is 100 percent. Many of them live at Pension Fridhem, which is a large, privately owned, red-painted wooden house at a walking distance from the factory. There are pensions where people stay to rest, and there are pensions, such as Friden in Alingsås and Fridhem in Södertälje, where people stay to work.

One of the residents at Pension Fridhem is Auntie Ilonka, who comes from Bergen-Belsen via the aliens’ camp at Kummelnäs, outside Stockholm, where on September 20, 1945, she’s declared fit and “ready to be sent to work.” A year later she marries Uncle Birger from Sundsvall and changes her surname from Hellman to Sundberg and moves from Pension Fridhem to a cold-water apartment with a dry privy in the yard, not far from the big pharmaceutical factory, and some years after that to a fully modern flat in the newly built, eight-story apartment house at the other end of the rowanberry avenue. Uncle Birger works at the truck factory and earns money on the side as an insurance salesman, and Auntie Ilonka soon stops sewing for Tornvall’s and opens a tobacconist’s shop in a red-brick apartment building, and as far as I can tell they’re an ill-matched and happy couple. Their marriage is childless, but in their home I’m their child. It’s a fragile home, full of glittering china and glass figurines, crystal chandeliers hanging from the ceiling, embroidered lace cloths on the tables, and sets of hardback novels in matching bindings on the bookshelves. The tables are laid with thin, gold-edged china cups and saucers with elegant floral patterns, lemonade glasses with drinking straws, and serving plates in nickel silver filled with homemade cakes, buns, and Swiss rolls. Auntie Ilonka’s deep love of children often expresses itself in highly calorific forms. Their home is also one of the first to boast a radio gramophone of dark mahogany, and at the earliest possible instant, a piece of furniture combining the radio gramophone with a television. When the television broadcasts live matches from the Stockholm World Cup in 1958, we put the radio commentary on. No one can stand the silence on TV. There has to be that constant radio blare, otherwise nothing can really be happening, can it? Auntie Ilonka has glittering black eyes and a gold tooth that glints when she laughs, and her Swedish sings with a different lilt from yours. There’s a Polish lilt and a Hungarian lilt, and I grow up to the sound of them both. Uncle Birger speaks a northern Swedish dialect, and the dishes served in their kitchen are somehow northern as well, often lingonberries. If Auntie Ilonka has brought any dishes from her home in the previous world, I don’t remember them. What I remember is meatballs with cream sauce and lingonberries. And the cakes. And Uncle Birger’s northern lilt as he says my name. There’s no need for you to say good-bye to Auntie Ilonka, or to Auntie Ethel who marries Uncle Sven, Birger’s brother, or to Uncle Miklós and Auntie Elisabeth, who live across the railroad bridge and are staying on here for roughly the same reasons as you are.

Читать дальше