In the small one-room apartment overlooking the railroad platform, there’s no room for machines. In the two-room apartment on the other side of the rowanberry avenue, there’s room for a round, sausagelike Volta vacuum cleaner, but it fails to make me a button-happy vacuum mechanic. I fear my mother is one of those weighed down by the bad habits of previous generations. To make my favorite dish, she sets sheets of newspaper alight in the sink and singes the last feathers off a chicken. Chicken soup is food for weekends and special days, as is gefilte fish, which she makes with fresh bream that she buys from the lift-netters on inner Maren, the small sea inlet in the middle of town. The big lift nets are wound up and down from little boats moored to the quayside. The bream have big scales that glitter as they flap in the lift nets. On the draining board in the kitchen, they’re still flapping. By the time Mom has scaled and stuffed them, they’re not flapping anymore.

I think the only semiprocessed product she ever uses is frozen cod fillet. She breads and fries the fillets until they’re an appetizing golden brown, but frozen cod fillet isn’t my favorite semiprocessed product. Frozen food is seen as a major step along the road to easier and more enjoyable housework, but I can’t fathom why, because there’s not a single kitchen in the apartment blocks along the rowanberry avenue with a freezer to keep the frozen food in, only a refrigerator at most, where you can’t even keep ice cream for more than an hour or two. For a while the new Co-op below the railroad station boasts the biggest freezer cabinet in town (10.8 shelf meters of cold, as the local paper puts it), and it’s precisely here that so many housewives and so many children and so many big plans for the future can be found.

Big plans for the future are the hallmark of the Place. It’s believed to have a great future, although the plans haven’t yet been finalized. Since the railroad drew a line through the plans for a meandering garden city with a church on a hilltop and a square with a covered market and a tram running to the sea, there are now plans for a modern cityscape housing six thousand people. A new tunnel will be dug through the high embankment, and around the growing cityscape land will be set aside for new homes, industries, and workplaces.

Including the land where the rowanberry avenue ends and the forest toward Havsbadet begins.

Beneath the sparse pines behind the Co-op, town planning architect Fritz Voigt is planning a playground, and in the forest toward Havsbadet he’s planning industrial units.

The forest is larger in my memory than in real life. In my memory the forest is both dark and light, and the houses on the rowanberry avenue are both visible and invisible from it, and the trampled paths through it are both familiar and secret.

A forest doesn’t need to be any larger than that to compete with architect Voigt’s playground.

Architect Voigt has plans for the town center, too. One plan is to make more space for the growing numbers of cars that have to pass through the center on their way between Stockholm and the world. This plan presupposes that large parts of the existing center will be pulled down and rebuilt, and that the low wooden buildings along narrow pedestrian streets will be replaced by tall concrete buildings along wide thoroughfares. In America, architect Voigt has learned that cars can be parked on third and fourth “decks” above shops at ground level. For the fifth floor he proposes “a green deck” with playgrounds for children. That way, the cars that have to pass through the town center anyway will have an opportunity and a reason to stop for a while.

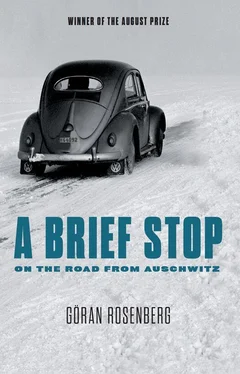

On Sunday afternoons, the growing numbers of cars that have to pass through the center of town are congested into traffic lines several kilometers long. Most of the car models are bulbous in shape: Saabs, Volvos, Morrises, DKWs, and Volkswagens, all shimmering like beetles in the sun. From a rise just above the southern approach to the town, I can see the line stretching to the horizon and unmoving for long periods of time. The air must be blue-hazed from all the exhaust fumes and heavy with the noise of engines, but I’m deaf and blind to such things. I keep a note of unusual makes of car and unfamiliar license plate numbers in a school exercise book. In Sweden, cars are registered by county. The local ones all have a B, the cars from Stockholm an A. It’s much less common to see a Z, Y, AC, or BD. I can’t imagine that the recording of car makes and plate numbers is my idea; I never learn to recognize car makes, yet there I am, sitting on the rise with someone I can’t remember, taking an interest in car makes and plate numbers. The traffic jams are an intrusive Sunday sight and we have to come up with something to make it more fun. The best thing of all is to stand by the bridge over the canal, see the drawbridge rising, and watch the motorists reluctantly getting out of their cars to catch a glimpse of the ship interrupting their passage, and listen to them complain about the “drawbridge misery.”

The bridge across the canal splits the little town into its two historically incompatible interests. The interests of those who just want to pass through demand the quickest possible thoroughfare, while the interests of those who want people to make a stop demand that they be able to slow down, park, and get out of their cars. The years when I’m noting down the exotic plate numbers of cars in stationary traffic lines are the years when the big plans for the town center are finalized. One plan proposes pulling down the old wooden buildings and widening the shopping street to provide more space for the cars and the thoroughfare while also making room for cars to stop for a while. The other plan proposes that a new road and a new bridge over the canal bypass the heart of the town, taking a route near the railroad bridge, leaving Södertälje on a turning off the main highway, just as it was left at the end of a spur off the main railroad line.

For a time the plans exist side by side, unresolved.

All futures still seem compatible and possible.

Everything that’s new heralds brighter times, including the traffic lines and the drawbridge misery.

If a forest or a town or a bathing beach happens to stand in the future’s way, the future has precedence.

I prefer traveling by train rather than by car. The train that runs on the single-track spur between Södertälje Södra and Södertälje Central is powered by a shunting engine and has coaches with open platforms and wooden benches. The journey takes five minutes. From fourth grade on, I take the train to school. The train to Stockholm has bigger engines and bigger coaches with corridors and compartments with upholstered seats. On the express trains making their brief stop at Platform 1, closest to the rowanberry avenue, there are coaches going to Copenhagen and Hamburg, and clattering dining cars, and sleeping cars from foreign railroad companies marked Schlafwagen or Wagon-Lit, their curtains drawn. One day I find myself peddling the Södertälje specialty, twisted buns, on Platform 1. Or perhaps someone else is in charge of the peddling and is just letting me have a try. The memory fragment will not shine forth. The passengers reach out from the windows. Where are they going? Where have they come from? With trains, you always know that sort of thing. It’s written on the signs hanging down from the platform roofs and on the signs attached to the sides of the coaches, and it’s announced from the loudspeakers fixed to the platform pillars. On Platform 1 I stay in close and frequent contact with the towns of Katrineholm, Hallsberg, Nässjö, and Alvesta, and by extension with the world as far as I can imagine it. I can’t imagine the world any farther than the town of Borås, with a change of train in Herrljunga. In Borås there are black steam trains, hissing and belching out smoke. Borås is where my uncle Natek and my two cousins live. Trains are for traveling from one place to another. Trains don’t run or stop just anywhere. Taking the train is always a bit of a ceremony, and people buy special platform tickets so they can meet and wave good-bye, and laugh and cry as the trains pull in and out of Platform 1 and the rowanberry avenue comes into and out of view.

Читать дальше