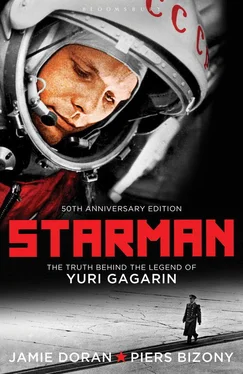

On April 3 the two rival cosmonauts dressed up in the reserve spacesuits for one last time so that they could be filmed climbing into Vostok. They took it in turns to make a moving farewell speech at the foot of the launch gantry. No clear details of the R-7’s appearance were revealed in these shots, because the rocket was still sitting horizontally in the assembly hangar – and its design details were highly secret. The launch technicians mimed the procedures for sealing the cosmonauts up in the ball, these sequences being staged in another area of the main spacecraft preparation hangar, not at the launch pad itself. In the months to come, several faked scenes would be spliced into brief but genuine shots of the launch preparations, taken under much less favourable conditions by cameraman Vladimir Suvorov. On the big day, gantry staff would not be able to give him such full access as he could fake in the hangar. [2] Cameraman Vladimir Suvorov’s account of his work can be found in Suvorov, Vladimir & Sabelnikov, Alexander, The First Manned Spaceflight , Commack, NY: Nova Science Publishers, 1997, pp. 61–75.

On April 7 Titov and Gagarin accompanied Kamanin to the launch pad. They inspected the gantry equipment in detail and rehearsed how to get off the pad if a fire broke out. If a cosmonaut was sealed into the ball and something went wrong before the R-7 rocket had even left the ground, the ejection seat would hurl him away from trouble, but at this low altitude he would never get high enough into the sky to open his parachute to its fullest extent. So the engineers had worked out the ‘catapulting distance’ of the seat and built a huge array of netting on the ground 1,500 metres away from the pad. The cosmonaut would fall into this, just so long as all the calculations were right. A mannequin had made this trip a few times, but now it was for real.

Kamanin reminded the cosmonauts about the manual option. If they were sitting on the pad awaiting lift-off and the blockhouse computers decided that something was wrong with the rocket, then the cosmonaut’s seat would automatically eject. Failing that, Sergei Korolev in the control bunker had a special key to activate the seat by remote control, according to his own judgement. Typically he would not trust himself alone. He ordered that two other level-headed people in the bunker should also be assigned such keys. But what if none of these safety options worked properly in a crisis? Then the cosmonaut would have to fire the seat on his own initiative, just like a pilot consciously deciding to bail out of a stricken MiG.

At this point in the lecture, Titov made a casual but most unfortunate remark, as recounted in Kamanin’s diary for April 7. ‘Worrying about this is probably a waste of time. The automatic ejection system will work without a hitch.’

Kamanin then turned to his other candidate. ‘Yuri, what do you think?’

Gagarin considered carefully before answering. Reading his answer, one can assume that he did not want to embarrass Titov or insult the skills of all those engineers who had built the automatic systems, although Kamanin obviously wanted to hear a different opinion. ‘I agree, the automatic systems won’t let us down,’ Gagarin replied, giving Titov some covering fire and expressing proper confidence in the ship’s design. ‘But if I know that I can eject for myself in case of failure, then that’ll simply increase my overall chances.’ Kamanin made no particular response, but he carefully noted down the entire exchange:

I kept a close eye on Gagarin, and he did well today. Calmness, self-confidence and knowledgeability were his main characteristics. I’ve not noticed a single inappropriate detail in his behaviour. [3] Kamanin diaries, April 7, 1961.

In fact, Kamanin seemed to be having a hard time deciding which man should be the first to fly. Only the day before he had been leaning towards Titov:

He does his exercises and training more accurately and doesn’t waste his time on idle chatter. As to Gagarin, he voices doubts about the importance of the automatic spare parachute release… I had already suggested in one of my earlier talks that the cosmonauts make a training ejection from an aircraft, but Gagarin appeared reluctant to do this.

Kamanin seemed to accuse each of the two prime cosmonauts of similar failings with regard to the parachute escape training. Ultimately his final recommendation may have been influenced by a factor beyond his control: the political requirement to favour a farmboy over a teacher’s son. However, his diaries suggest a more subtle reason for his ultimate recommendation:

Titov is of a stronger character. The only thing that keeps me away from deciding in his favour is the necessity to keep a stronger cosmonaut for a 24-hour flight… It’s hard to decide which of them should be sent to die, and it’s equally hard to decide which of these two decent men should be made famous worldwide.

Kamanin obviously believed that Gagarin was capable of flying the single-orbit mission that had now been decided upon for the first manned space flight. He kept Titov in reserve for a more demanding longer flight in the near future. In the circumstances, Titov could not possibly have been expected to see this reasoning as a compliment on his superior discipline.

Some while before he made his fatal mistake with the R-16, Marshal Nedelin constructed a wooden summerhouse at Baikonur as a pleasant change of scene from the usual drab barracks and drearily functional blockhouses. It had an open framework, more like a gazebo than a proper building; a wooden floor; archways, trellises and columns prettily decorated in blue and white. A cool stream trickled nearby. In the cold of winter it was impossible to make sensible use of the building. The airless summer was also impractical, but in April, when the steppe was in blossom for a few weeks and the air was sweet with the scent of wormwood… There were times when the summerhouse was perfect for a party.

Today, white-haired 63-year-old Gherman Titov bemoans the old summerhouse’s sorry state. ‘It’s windy here now. There were some elm trees, but they cut them down. They should have been replaced, but no one cares. New Russians aren’t interested. For them, flying into space is just a business. At least under Nikita Khrushchev cosmonautics was developing. Under the modern Democrats everything just falls down. What’s all this history for? Silly fools, they don’t understand that when they die, memories of them will also be destroyed. There won’t be a single bump left. Not even a grave.’

History is important to Titov, because it was in this summerhouse on April 9, 1961, just three days before the first manned Vostok flight was scheduled, that they celebrated his removal from greatness with vodka, fresh oranges, apples and other splendid foods laid out on a long table. Vladimir Suvorov, the official cameraman, caught the scene on colour film.

The previous day, Suvorov’s camera had recorded a more formal event in another part of Baikonur, a special State Committee headed by Korolev, Keldysh and Kamanin, during which the First Cosmonaut was selected. The six prime candidates were standing before them. At the pivotal moment a proud Yuri Gagarin stepped forward to receive his historic commission. In fact, the whole thing was staged. The Committee had already met the previous day, in secret session, with none of the cosmonauts present. Afterwards Nikolai Kamanin summoned Titov and Gagarin to his office and told them, just like that. Gagarin was to be commander and Titov his back-up, his ‘understudy’. No explanations. Nothing. Just the awful fact of it, and Gagarin suppressing his usual grin and promising to perform his duties well. Titov says, ‘Some people will tell you I gave him a hug. Nonsense! There was none of that. However, the decision had been taken. I understood that.’ Kamanin noted in his diary that ‘Titov’s disappointment was quite obvious.’

Читать дальше