Samuel Coleridge - The Literary Remains of Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Volume 3

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Samuel Coleridge - The Literary Remains of Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Volume 3» — ознакомительный отрывок электронной книги совершенно бесплатно, а после прочтения отрывка купить полную версию. В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Биографии и Мемуары, Критика, Языкознание, foreign_antique, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Literary Remains of Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Volume 3

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Literary Remains of Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Volume 3: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Literary Remains of Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Volume 3»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Literary Remains of Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Volume 3 — читать онлайн ознакомительный отрывок

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Literary Remains of Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Volume 3», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Append. Part. I. s. 4. p. 752.

And again he saith, that every soul, immediately upon the departure hence, is in this appointed invisible place, having there either pain, or ease and refreshing; that there the rich man is in pain, and the poor in a comfortable estate. For, saith he, why should we not think, that the souls are tormented, or refreshed in this invisible place, appointed for them in expectation of the future judgment?

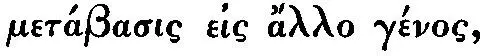

This may be adduced as an instance, specially, of the evil consequences of introducing the idolon of time as an ens reale into spiritual doctrines, thus understanding literally what St. Paul had expressed by figure and adaptation. Hence the doctrine of a middle state, and hence Purgatory with all its abominations; and an instance, generally, of the incalculable possible importance of speculative errors on the happiness and virtue of man-kind.

Notes on Donne 30 30 The LXXX Sermons, fol. 1640. – Ed.

There have been many, and those illustrious, divines in our Church from Elizabeth to the present day, who, overvaluing the accident of antiquity, and arbitrarily determining the appropriation of the words 'ancient,' 'primitive,' and the like to a certain date, as for example, to all before the fourth, fifth, or sixth century, were resolute protesters against the corruptions and tyranny of the Romish hierarch, and yet lagged behind Luther and the Reformers of the first generation. Hence I have long seen the necessity or expedience of a threefold division of divines. There are many, whom God forbid that I should call Papistic, or, like Laud, Montague, Heylyn, and others, longing for a Pope at Lambeth, whom yet I dare not name Apostolic. Therefore I divide our theologians into,

1. Apostolic or Pauline:

2. Patristic:

3. Papal.

Even in Donne, and still more in Bishops Andrews and Hackett, there is a strong Patristic leaven. In Jeremy Taylor this taste for the Fathers and all the Saints and Schoolmen before the Reformation amounted to a dislike of the divines of the continental Protestant Churches, Lutheran or Calvinistic. But this must, in part at least, be attributed to Taylor's keen feelings as a Carlist, and a sufferer by the Puritan anti-prelatic party.

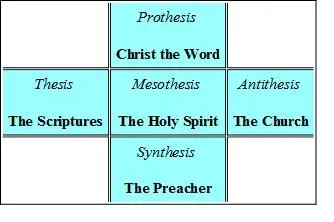

I would thus class the pentad of operative Christianity: —

The Papacy elevated the Church to the virtual exclusion or suppression of the Scriptures: the modern Church of England, since Chillingworth, has so raised up the Scriptures as to annul the Church; both alike have quenched the Holy Spirit, as the mesothesis of the two, and substituted an alien compound for the genuine Preacher, who should be the synthesis of the Scriptures and the Church, and the sensible voice of the Holy Spirit.

Serm. I. Coloss. i. 19, 20. p. 1.

Ib. E.

What could God pay for me? What could God suffer? God himself could not; and therefore God hath taken a body that could.

God forgive me, – or those who first set abroad this strange  this debtor and creditor scheme of expounding the mystery of Redemption, or both! But I never can read the words, 'God himself could not; and therefore took a body that could' – without being reminded of the monkey that took the cat's paw to take the chestnuts out of the fire, and claimed the merit of puss's sufferings. I am sure, however, that the ludicrous images, under which this gloss of the Calvinists embodies itself to my fancy, never disturb my recollections of the adorable mystery itself. It is clear that a body, remaining a body, can only suffer as a body: for no faith can enable us to believe that the same thing can be at once A. and not A. Now that the body of our Lord was not transelemented or transnatured by the pleroma indwelling, we are positively assured by Scripture. Therefore it would follow from this most unscriptural doctrine, that the divine justice had satisfaction made to it by the suffering of a body which had been brought into existence for this special purpose, in lieu of the debt of eternal misery due from, and leviable on, the bodies and souls of all mankind! It is to this gross perversion of the sublime idea of the Redemption by the cross, that we must attribute the rejection of the doctrine of redemption by the Unitarian, and of the Gospel in toto by the more consequent Deist.

this debtor and creditor scheme of expounding the mystery of Redemption, or both! But I never can read the words, 'God himself could not; and therefore took a body that could' – without being reminded of the monkey that took the cat's paw to take the chestnuts out of the fire, and claimed the merit of puss's sufferings. I am sure, however, that the ludicrous images, under which this gloss of the Calvinists embodies itself to my fancy, never disturb my recollections of the adorable mystery itself. It is clear that a body, remaining a body, can only suffer as a body: for no faith can enable us to believe that the same thing can be at once A. and not A. Now that the body of our Lord was not transelemented or transnatured by the pleroma indwelling, we are positively assured by Scripture. Therefore it would follow from this most unscriptural doctrine, that the divine justice had satisfaction made to it by the suffering of a body which had been brought into existence for this special purpose, in lieu of the debt of eternal misery due from, and leviable on, the bodies and souls of all mankind! It is to this gross perversion of the sublime idea of the Redemption by the cross, that we must attribute the rejection of the doctrine of redemption by the Unitarian, and of the Gospel in toto by the more consequent Deist.

Ib. p. 2. C.

And yet, even this dwelling fullness, even in this person Christ Jesus, by no title of merit in himself, but only quia complacuit , because it pleased the Father it should be so.

This, in the intention of the preacher, may have been sound, but was it safe, divinity? In order to the latter, methinks, a less equivocal word than 'person' ought to have been adopted; as 'the body and soul of the man Jesus, considered abstractedly from the divine Logos, who in it took up humanity into deity, and was Christ Jesus.' Dare we say that there was no self-subsistent, though we admit no self-originated, merit in the Christ? It seems plain to me, that in this and sundry other passages of St. Paul, the Father means the total triune Godhead.

It appears to me, that dividing the Church of England into two æras – the first from Ridley to Field, or from Edward VI to the commencement of the latter third of the reign of James I, and the second ending with Bull and Stillingfleet, we might characterize their comparative excellences thus: That the divines of the first æra had a deeper, more genial, and a more practical insight into the mystery of Redemption, in the relation of man toward both the act and the author, namely, in all the inchoative states, the regeneration and the operations of saving grace generally; – while those of the second æra possessed clearer and distincter views concerning the nature and necessity of Redemption, in the relation of God toward man, and concerning the connection of Redemption with the article of Tri-unity; and above all, that they surpassed their predecessors in a more safe and determinate scheme of the divine economy of the three persons in the one undivided Godhead. This indeed, was mainly owing to Bishop Bull's masterly work De Fide Nicæna , 31 31 "Mr. Coleridge's admiration of Bull and Waterland as high theologians was very great. Bull he used to read in the Latin Defensio Fidei Nicoenoe , using the Jesuit Zola's edition of 1784, which, I think, he bought at Rome. He told me once, that when he was reading a Protestant English Bishop's work on the Trinity, in a copy edited by an Italian Jesuit in Italy, he felt proud of the Church of England, and in good humour with the Church of Rome." Table Talk, 2d edit. p. 41. – Ed.

which in the next generation Waterland so admirably maintained, on the one hand, against the philosophy of the Arians, – the combat ending in the death and burial of Arianism, and its descent and metempsychosis into Socinianism, and thence again into modern Unitarianism, – and on the other extreme, against the oscillatory creed of Sherlock, now swinging to Tritheism in the recoil from Sabellianism, and again to Sabellianism in the recoil from Tritheism.

Ib.

First, we are to consider this fullness to have been in Christ, and then, from this fullness arose his merits; we can consider no merit in Christ himself before, whereby he should merit this fullness; for this fullness was in him before he merited any thing; and but for this fullness he had not so merited. Ille homo, ut in unitatem filii Dei assumeretur, unde meruit ? How did that man (says St. Augustine, speaking of Christ, as of the son of man), how did that man merit to be united in one person with the eternal Son of God? Quid egit ante? Quid credidit ? What had he done? Nay, what had he believed? Had he either faith or works before that union of both natures?

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Literary Remains of Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Volume 3»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Literary Remains of Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Volume 3» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Literary Remains of Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Volume 3» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.