Recently, we’d developed this trick even more. The grip he exerted when he grabbed my arms to reach the treat was as strong as a vice. So every now and again I would slowly and very gently raise him in the air so that he was dangling a few inches above the ground.

He would hang there for a few seconds, until he let go and dropped down or I eased him back to earth. I always made sure he had a soft landing of course and usually put my rucksack under him.

The more of a ‘show’ we put on, the more people seemed to respond to us, and the more generous they became, not just in buying The Big Issue .

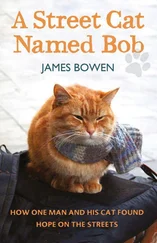

Since our early days at Angel, people had been incredibly kind, dropping off snacks and nibbles not just for Bob, but for me as well. But they had also started giving us items of clothing, often hand-knitted or sewn by them.

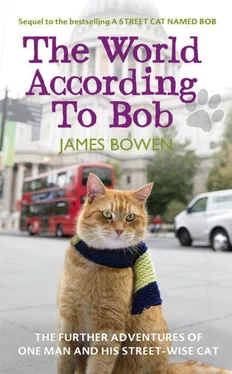

Bob now had a collection of scarves in all sorts of colours. So many, in fact, that I was running out of space to keep them all. He must have had two dozen or more! He was fast becoming to scarves what Imelda Marcos had been to shoes.

It was a little overwhelming at times to know that we were on the receiving end of such warmth, support and love. But I never for a moment kidded myself that there weren’t those who felt very differently about us. They were never very far away…

It was approaching the busiest time of the week, the Friday evening rush hour, and the crowds passing in and out of Angel tube were growing thicker by the minute. While I wheeled around the street trying to sell my stack of magazines, Bob was totally oblivious to the commotion, flapping his tail absent-mindedly from side to side as he lay on my rucksack on the pavement.

It was only when things had died down, around 7pm, that I noticed a lady standing a few feet away from us. I had no idea how long she had been there, but she was staring intently, almost obsessively at Bob.

From the way she was muttering to herself and shaking her head from side to side occasionally, I sensed she disapproved of us somehow. I had no intention of engaging her in conversation, not least because I was too busy trying to sell the last few copies of the magazine before the weekend.

Unfortunately, she had other ideas.

‘Young man. Can’t you see that this cat is in distress?’, she said, approaching us.

Outwardly, she looked like a school teacher, or even a headmistress, from some upper-class public school. She was middle-aged, spoke in a clipped, cut-glass English accent and was dressed in a scruffy and un-ironed tweed skirt and jacket. Given her manner, however, I doubted very much that any school would have employed her. She was brusque, bordering on the downright aggressive.

I sensed she was trouble, so didn’t respond to her. She was obviously determined to pick a fight, however.

‘I have been watching you for a while and I can see that your cat is wagging its tail. Do you know what that means?’ she said.

I shrugged. I knew she was going to answer her own question in any case.

‘It means it’s not happy. You shouldn’t be exploiting it like this. I don’t think you’re fit to look after him.’

I’d been around this track so many times since Bob and I had started working the streets together. But I was polite, so instead of telling this lady to mind her own business, I wearily began defending myself once again.

‘He’s wagging his tail because he’s content. If he didn’t want to be there, Madam, you wouldn’t see him for dust. He’s a cat. They choose who they want to be with. He’s free to run off whenever he wants.’

‘So why is he on a lead?’ she shot back, a smug look on her face.

‘He’s only on a lead here and when we are on the streets. He ran off once and was terrified when he couldn’t find me again. I let him off when he goes to do his business. So, again, if he wasn’t happy, as you claim, he’d be gone the minute I took the lead off wouldn’t he?’

I’d had this conversation a hundred times before and knew that for 99 people out of that 100, this was a rational and reasonable response. But this lady was part of the 1 per cent who were never going to take my word for it. She was one of those dogmatic individuals who believed they were always right and you were always wrong – and even more wrong if you were impertinent enough not to see their point of view.

‘No, no, no. It’s a well-known fact that if a cat is wagging its tail it is a distress signal,’ she said, more animated now. I noticed that her face was quite red. She was flapping her arms and pacing around us rather menacingly.

I could tell Bob was uncomfortable about her; he had an extremely good radar when it came to spotting trouble. He had stood up and begun backing himself towards me so that he was now standing between my legs, ready to jump up if things got out of hand.

One or two other people had stopped, curious to see what the fuss was about so I knew I had witnesses if the lady did or said anything outrageous.

We carried on arguing for a minute or two. I tried to ease her fears by telling her a little about us.

‘We’ve been together for more than two years. He wouldn’t have been with me two minutes if I was mistreating him,’ I said at one point. But she was intransigent. Whatever I said, she just shook her head and tutted away. She simply wasn’t willing to listen to my point of view. It was frustrating in the extreme, but there was nothing more I could do. I resigned myself to the fact that she was entitled to her opinion. ‘Why don’t we agree to differ?’ I said at one point.

‘Hffff,’ she said, waving her arms at me. ‘I’m not agreeing with anything you say young man.’

Eventually, to my huge relief, she started walking away, muttering and shaking her head as she shuffled off into the crowds jostling around the entrance to the tube station.

I watched her for a moment, but was soon distracted by a couple of customers. Fortunately, their attitude was the complete opposite of the one this lady had displayed. Their smiles were a welcome relief.

I was handing one of them their change when I heard a noise behind me that I recognised immediately. It was a loud, piercing wheeeeeow . I spun round and saw the woman in the tweed suit. Not only had she come back, she was now holding Bob in her arms.

Somehow, while I had been distracted, she had managed to scoop him up off the rucksack. She was now nursing him awkwardly, with no affection or empathy, one hand under his stomach and another on his back. It was strange, as if she’d never picked up an animal before in her life. She could have been holding a joint of meat that she’d just bought at the butcher or a large vegetable at a market.

Bob was clearly furious about being manhandled like this and was wriggling like crazy.

‘What the hell do you think you are doing?’ I shouted. ‘Put him down, right now or I’ll call the police.’

‘He needs to be taken somewhere safe,’ she said, a slightly crazed expression forming on her reddening face.

Oh God no, she’s going to run off with him , I said to myself, preparing to drop my supply of magazines and set off in hot pursuit through the streets of Islington.

Luckily, she hadn’t quite thought it through because Bob’s long lead was still tethered to my rucksack. For a moment there was a kind of stand-off. But then I saw her eye moving along the lead to the rucksack.

‘No you don’t,’ I said, stepping forward to intercept her.

My movement caught her off guard which in turn gave Bob his chance. He let out another screeching wheeeeow and freed himself from the woman’s grip. He didn’t scratch her but he did dig his paws into her arm which forced her to panic and suddenly drop him on to the pavement.

Читать дальше