As I waited for the prescription to be made up today, I didn’t really dwell on the significance of it. My head was too busy with thoughts about what lay ahead during the next forty-eight hours.

The counsellor had explained the risk to me in graphic detail. Coming off methadone wasn’t easy. In fact, it was really hard. I’d experience ‘clucking’ or ‘cold turkey’, a series of unpleasant physical and mental withdrawal symptoms. I had to wait for those symptoms to become quite severe before I could go back to the clinic to get my first dose of Subutex. If I didn’t I risked having what’s known as a precipitated withdrawal. This was basically a much worse withdrawal. It didn’t bear thinking about.

I was confident at this point that I could do it. But at the same time I had an awful niggling feeling that I could fail and find myself wanting to score something that would make me feel better. But I just kept telling myself that I had to do this, I had to get over this last hurdle. Otherwise it was going to be the same the next day and the next day and the day after that. Nothing was going to change.

This was the reality that had finally dawned on me. I’d been living this way for ten years. A lot of my life had just slipped away. I’d wasted so much time, sitting around watching the days vanish. When you are dependent on drugs, minutes become hours, hours become days. It all just slips by; time becomes inconsequential, you only start worrying about it when you need your next fix. You don’t even care until then.

But that’s when it becomes so awful. Then all you can think about is making money to get some more. I’d made huge progress since I’d been in the depths of my heroin addiction years earlier. The DDU had really put me back on track. But I was just sick of the whole thing now. Having to go to a chemist every day, having to visit the DDU every fortnight. Having to prove that I hadn’t been using. I had had enough. I now felt like I had something to do with my life.

In a way I’d made it harder on myself by insisting on doing it alone. I had been offered the chance several times to join Narcotics Anonymous but I just didn’t like the whole twelve-step programme. I couldn’t do that kind of quasi-religious thing. It’s almost like you have to give yourself up to a higher power. It just wasn’t me.

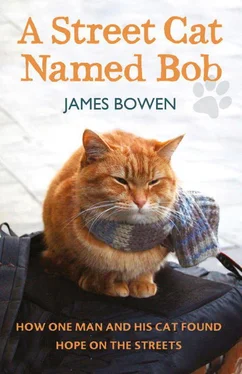

I realised that I was making life even more difficult for myself by taking that route. The difference was I didn’t think I was on my own now. I had Bob.

As usual, I didn’t take him with me to the DDU clinic. I didn’t like exposing him to the place. It was a part of my life I wasn’t proud about, even though I did feel I’d achieved a lot since I’d first visited.

When I got home he was pleased to see me, especially as I’d stopped off at the supermarket on the way home and had a bag full of goodies intended to get us through the next two days. Anyone who is trying to get rid of an addictive habit knows what it is like. Whether it’s trying to give up cigarettes or alcohol, the first forty-eight hours are the hardest. You are so used to getting your ‘fix’ that you can’t think of anything else. The trick is to think of something else, obviously. And that’s what I hoped to do. And I was just really grateful that I had Bob to help me achieve it.

That lunchtime we sat down in front of the television, had a snack together – and waited.

The methadone generally lasted for around twenty hours so the first part of the day passed easily enough. Bob and I played around a lot and went out for a short walk so that he could do his business. I played a really old version of the original Halo 2 game on my knackered old Xbox. At that point it all seemed to be plain sailing. I knew it couldn’t stay that way for much longer.

Probably the most famous recreation of someone ‘clucking’ is in the film Trainspotting in which Ewan McGregor’s character, Renton, decides to rid himself of his heroin addiction. He is locked in a room with a few days of food and drink and left to get on with it. He goes through the most horrendous physical and mental experience you can imagine, getting the shakes, having hallucinations, being sick. All that stuff. Everyone remembers the bit where he imagines he is climbing inside the toilet bowl.

What I went through over the next forty-eight hours felt ten times worse than that.

The withdrawal symptoms began to kick in just after twenty-four hours after I’d had my dose of methadone. Within eight hours of that I was sweating profusely and feeling very twitchy. By now it was the middle of the night and I should have been asleep. I did nod off but I felt like I was pretty much conscious all the time. It was a strange kind of sleep, full of dreams or, more accurately, hallucinations.

It’s hard to recollect exactly, but I do remember having these lucid dreams about scoring heroin. There were a lot of these dreams and they always went the same way: I would either score and spill it, score and not be able to get a needle into my vein or score but then get arrested by the police before I could use it. It was weird. It was obviously my body’s way of registering the fact that it was being denied this substance that it had once been used to being fed every twelve hours or so. But it was also my subconscious trying to persuade me that maybe it was a good idea to start using it again. Deep in my brain there was obviously this huge battle of wills going on. It was almost as if I was a bystander, watching it all happen to someone else.

It was strange. Coming off heroin years ago wasn’t as bad. The transition to methadone had been reasonably straightforward. This was a different experience altogether.

Time ceased to have any real meaning, but by the following morning I was beginning to experience really bad headaches, almost migraine-level pains. As a result I found it hard to cope with any light or noise. I’d try and sit in the dark, but then I’d start dreaming or hallucinating and want to snap myself out of it. It was a vicious circle.

What I needed more than anything was something to take my mind off it all, which was where Bob proved my salvation.

There were times when I wondered whether Bob and I had some kind of telepathic understanding. He could definitely read my mind sometimes, and seemed to be doing so now. He knew that I needed him so he was a constant presence, hanging around me, snuggling up close when I invited him but keeping his distance when I was having a bad time.

It was as if he knew what I was feeling. Sometimes I’d be nodding off and he would come up to me and place his face close to me, as if to say: ‘You all right, mate? I’m here if you need me.’ At other times he would just sit with me, purring away, rubbing his tail on me and licking my face every now and again. As I slipped in and out of a weird, hallucinatory universe, he was my sheet anchor to reality.

He was a godsend in other ways too. For a start, he gave me something to do. I still had to feed him, which I did regularly. The process of going into the kitchen, opening up a sachet of food and mixing it in the bowl was just the sort of thing I needed to get my mind off what I was going through. I didn’t feel up to going downstairs to help him do his business, but when I let him out he dashed off and was back upstairs again in what seemed like a few minutes. He didn’t seem to want to leave my side.

I’d have periods where I didn’t feel so bad. During the morning of the second day, for instance, I had a couple of hours where I felt much better. Bob and I just played around a lot. I did a bit of reading. It was hard but it was a way to keep my mind occupied. I read a really good non-fiction book about a Marine saving dogs in Afghanistan. It was good to think about what was going on in someone else’s life.

Читать дальше