From then on, nothing in my life ever turned out as expected. Having chosen a rather dull and safe career, I ended up as leader of one of the country’s intelligence agencies and a target for terrorists. Having conventionally married my schoolfriend, I ended up separated, a single parent. Having begun work in the days when women’s careers were not taken at all seriously and most lasted only between education and motherhood, I ended up advising ministers and Prime Ministers.

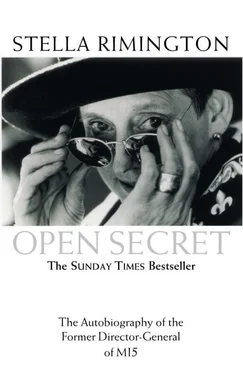

During my career, I have seen myself portrayed publicly in various different guises; in the 1980s I was Mrs Thatcher’s stooge, the leader of an arm of the secret state which was helping her to beat the miners’ strike and destroy the NUM. I was portrayed as the investigator of CND and even as the one who had ordered the murder of an old lady peace campaigner. In 1992, when I first emerged into the public gaze as Director-General of MI5, I became a sort of female James Bond, ‘Housewife Superspy’, ‘Mother of Two Gets Tough with Terrorists’. And finally, with the writing of this book, I have become to some a villain, ‘Reckless Rimington’, careless of our national security, opening the door to floods of reminiscences and damaging revelations. I don’t recognise myself in any of those roles.

The unexpected course of my life has involved me closely with some of the significant issues of the late 20th century: the rise of terrorism, the end of the Cold War and some of the big social questions – women’s place in society (how can work and family be combined?) civil liberties (how far should the state intrude on the citizens’ privacy to ensure their safety?) and open government (how much should the public know about the secret state and how should it be controlled?).

I have observed and participated in these issues from an unusual position, inside the secret state. But that does not mean my perspective is distorted or warped. Ian Fleming and John le Carré in their different ways have done the intelligence world few favours. The vast majority of those who work inside it are balanced, sane and sensible people, with a well developed sense of humour and a down-to-earth approach to the difficult issues they have to deal with. They have all the same problems in their lives as everyone else but they are, as I said publicly in 1994 in the Dimbleby Lecture on BBC TV, ‘positive, forward-looking and flexible and work hard to defend this country and its citizens against threats to its security’.

On a May day in 1940, when I was just five, I had my first experience of the ‘need to know’ principle in action. My brother Brian and I attended the primary school in Ingatestone in Essex, some five miles from the house in Margaretting which my parents had rented to get us all out of London at the beginning of the war. That day, we came out of school as usual and waited at the bus stop outside the bank for our bus to take us home. But on that particular day, though we waited and waited, no bus came. As it later turned out, all the buses, as well as all other transport, had been commandeered to help in the evacuation from Dunkirk. I suppose because it was Top Secret no warning had been given, and there we were aged five and eight, completely cut off from home, waiting and waiting for a bus to come while at the other end my mother waited and waited for us to turn up, with no idea of what had happened to us. There were no telephones and no cars and no way for the two ends to communicate.

Eventually, the bank manager noticed us standing there and arranged for us to be taken home in someone’s pony and trap, the only transport available. From then until we moved on, the pony and trap became our normal mode of transport to school.

Like those of most people born in Europe in the first half of the 1930s, all my earliest memories are dominated by the war and its anxieties and uncertainties. My father was on the high seas when war broke out, returning from working on an engineering contract in Venezuela. Though I was only four, my mother’s anxiety easily transferred itself to me. I can remember her coming out into our back garden, where Brian and I were playing in the sun.

She was wearing one of those flowery wrap-around cotton aprons, which 1930s suburban housewives seem always to be wearing in photographs of that period. She had come out to tell us what she had heard on the wireless about the outbreak of war, and the latest news of where Father was. She was worried and she needed to share her anxiety. Even though I didn’t understand it all, I felt anxious for the first time in my life. It was an anxiety that was to last a long time.

Father got home safely, and he told us about the boat drills the crew had carried out for all the passengers on board ship, in case they got torpedoed, and how they had painted a huge stars and stripes on the deck of the ship to indicate to enemy aircraft that they were neutral. Father greeted the arrival of the Second World War with immense sadness and depression. He had been seriously wounded in the Great War at Passchendaele, attempting to mine the German trenches. He had volunteered young, disguising his real age. He thought he was fighting in the war to end all wars, for a world fit for heroes to live in. He had been unemployed during the Depression and now a second war seemed to him the crowning blow.

We lived at the time in the new house in South Norwood, which my parents had bought in 1929, shortly after they got married, in high hopes of a prosperous future. But it was obvious to Father that we could not stay there now war had broken out; the London suburbs were much too dangerous a place for his wife and young family. For a time he and Mother toyed with the idea of sending my brother and me to America to spend the war with his sister, who had emigrated to Philadelphia. In fact everything was in place for us to go, when one of the ships carrying children to Canada was torpedoed. Mother, who had never liked the idea of sending us away in the first place, decided that whatever happened we would all stay together.

So instead we rented what seemed to me an enormous house – but was in fact a moderate-sized detached dwelling, ‘St Martins’ at Margaretting in Essex. This was the first of a whole series of rented houses which we lived in throughout my childhood. That move was financially disastrous, and effectively made it certain that my parents would never be even moderately comfortably off by middle-class standards. They let our London house to an unmarried lady for a trifling rent – the only sort of rent you could get for a house in South Norwood in 1939. She thus established a protected tenancy and, as we never returned to live in London, my parents were never afterwards able to get her out so that they could sell the house. In the 1950s, despairing of getting any of their capital back, they sold it to her for a song.

Moving to St Martin’s in September 1939 was hugely exciting for us children. First of all came the journey in a taxi with a black fabric hood and a very small, almost opaque, cracked yellow window, through which I tried to look back as South Norwood disappeared.

We went through the ‘Rotherhithe Pipe’ as the driver called it, the tunnel under the Thames, and into what was then the countryside of Essex. I remember the house well. It had a big galleried hall and a kitchen that was old-fashioned even by 1930s standards, with a door at each end. This meant that small children could rush through the kitchen and round the passages in circles, yelling with excitement and causing vast annoyance to anyone working in the kitchen. Less excitingly, for my mother at least, the house had rats in the roof, which scampered loudly overhead and seemed in imminent danger of falling through the large number of cracks in the ceiling into the bedrooms.

Читать дальше