We did much better on time, and by 20:00 that night we had skirted the marshy river area where we had wasted so much time two nights before.

Diedies took the lead after the river. As adept as I was at map and compass work, he had a knack for memorising a target and working it along the planned penetration route. This time we reached the runway by midnight. We briefly considered finding a hiding place inside the base should we not make it back to safety before first light, but both of us knew how dangerous that would be.

We kept going, maintaining a low profile on the runway. Suddenly I heard a sound behind us and pushed Diedies down firmly. It was the strangest noise, as if a light steel object was being rolled rapidly in our direction. The next moment a dog came trotting past us on the runway, not noticing us even though we were barely three metres away. The noise came from its claws hitting the tarred surface. It ran past us and disappeared, leaving two shaken but very relieved operators on the tarmac.

We reached the hardstand in front of the main terminal building. As there was some light coming from the buildings, I could see quite clearly with the night-vision goggles. But there were no jets. The only two aircraft I could see were a smallish prop job and an Mi-17 transport helicopter, nothing else.

“I see no MiGs,” I said in a whisper.

“What do you mean, no MiGs? We’re not looking in the right place…”

He brought his night vision to his face. No fighter planes. Then it hit us, right there in the dark, on the tarmac, deep in the Angolan war zone. They didn’t put troops under the MiGs to guard them; they actually flew the aircraft out to a safe place every night! That was the jet activity we had heard the two previous nights.

We were devastated to realise that all our efforts were in vain – our mission would be unsuccessful. We approached the transport on the tarmac and saw that it was unserviceable. When I quietly suggested to Diedies that we should plant devices on the two aircraft, he just waved his arms; it would have been futile to give the game away at that point. All that remained was to exfiltrate quietly and rethink the whole operation.

We moved out fast. By now we knew the route well and skirted the hot spots easily. Once out of the target area, I took over and navigated us directly back to the TB. While it was a great relief to be out of danger and to see the friendly faces of our comrades, I felt very down and disappointed.

The next day we drove back to the UNITA base and were picked up by a Puma soon after our arrival. At Rundu we were met on the runway by Ormonde Power and Colonel Murphy and were sneaked off to Fort Foot in an enclosed van. We had the customary welcoming dinner with champagne and all, but for Diedies and me the evening was overshadowed by the fact that we hadn’t succeeded. At the back of my mind I was already considering what we would do next.

Shortly afterwards, we received confirmation via the intelligence channel that FAPLA evacuated the fighters every afternoon from Menongue to Huambo, which was much further from the border and thus considered safer. This was excellent information, fresh and accurate, but unfortunately three weeks too late.

7

Operation Angel

August 1987

AFTER THE ANC was banned by the National Party government, in 1960, many of its leaders went into exile. The organisation opened offices in several African countries, including Zambia, Tanzania, Angola, Botswana, Uganda and Zimbabwe. Umkhonto we Sizwe (MK), the ANC’s armed wing, also established a series of offices and training camps in the frontline states from where guerrilla operations into South Africa were launched.

Operation Angel

The 1980s saw the ANC taking the armed struggle against the apartheid regime to the next level, with an increase in attacks on civilian targets and a determined attempt to make the townships ungovernable. In 1985 the National Party government invoked the first state of emergency, and began to employ a variety of measures, some highly controversial, to counter the ANC.

One day late in 1986 Diedies and I were ordered to report to Special Forces HQ where we met Frans Fourie, a highly capable and very experienced officer from 4 Recce. A secluded intelligence meeting room had been prepared for our briefing. As a special measure to secure the venue, it was cordoned off and swept for bugs. Only once we were inside and introduced to representatives from the Department of Foreign Affairs and the National Intelligence Service did we realise the gravity of the moment. It soon turned out that we were to deploy with Frans on a highly sensitive secret mission. The operation clearly received the highest level of attention.

The meeting commenced with an intelligence overview of ANC deployments in countries neighbouring South Africa and a summary of events depicting the escalation of the threat against the state. Then the mission was conveyed to us: a raid was to be conducted in Tanzania, aimed at wiping out the entire top structure of the ANC. The operation had already been approved at the highest level and preparations had to commence immediately.

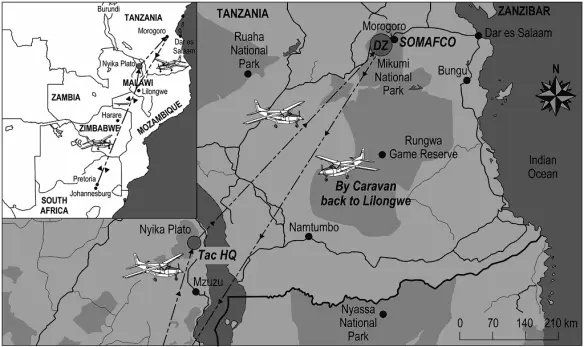

Our target was the Solomon Mahlangu Freedom College (SOMAFCO) in Mazimbu, near Morogoro in central Tanzania, where a special meeting of the ANC national executive committee would take place. The conference would be attended by all the significant leaders, including Oliver Tambo, then president of the ANC, Thabo Mbeki, Jacob Zuma and Chris Hani.

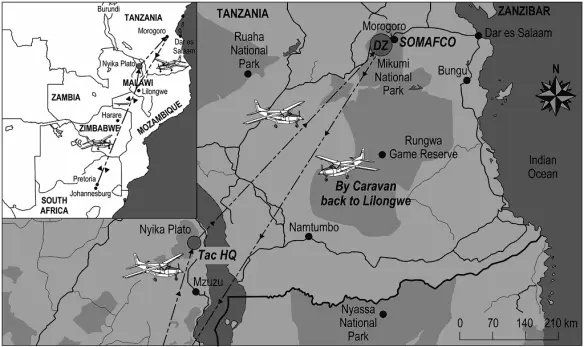

Our mission was to penetrate SOMAFCO and set explosive charges in the Hector Pieterson Conference Hall, the main venue at the facility. The plan was a rather elaborate but executable one. The team would be flown to Malawi’s Blantyre International Airport, and from there to the Nyika National Park in the northeast of the country. A secret base would be established at the Chelinda camp within the reserve for final preparation and E&E planning. It would also serve as Tac HQ and final staging point for the raid into Tanzania.

From Nyika, the team would be taken by civilian aircraft to a DZ in the Morogoro Crater. The plane would be guided in by an agent, known to us only by the code name Angel, for a parachute drop at low altitude. Angel had been recruited by Military Intelligence because of his intimate knowledge of the area and his ability to access African countries. After landing, the three-man team would meet up with Angel, who would orientate us and guide us in towards the target. Once in proximity to SOMAFCO, the agent would withdraw and the team would commence with the penetration. Charges would be planted in the main venue and the timing mechanisms set for 09:30 the next morning, when the conference was expected to be in full swing.

The team would withdraw to a remote airfield and would be picked up by fixed-wing aircraft and taken back to Malawi. If the pick-up was compromised and the team had to go into escape and evasion mode, the Tanzam railway line would be used as the escape and evacuation route, with predetermined RVs at landing strips along the line.

My first reaction was that the mission would be impossible due to the vast distances involved. My second thought was that the operation, if successful, would spark massive international criticism. But on both accounts a broad plan had already been drawn up.

With the briefings concluded, we started our planning and preparations. Hannes Venter, OC 4 Recce, was selected as the mission commander, and Dave Scales would act as Tac HQ coordinator. We worked through every available piece of information, studying maps and photos the intelligence officers managed to produce. The aerial photos were outdated but invaluable to the planning of our final penetration. We had to rely mostly on reports from secondary sources, with the result that detailed information about the target was lacking.

Читать дальше