During the mopping-up operations, we regularly found civilians who had been injured in the attack on the town four weeks previously, and our medics diligently attended to them. One incident that will always stay with me was when we found a woman lying in a dark little hut with a massive wound to her upper right leg. Gangrene had set in and her leg had swollen to twice the size of her frail body. The stench in the hut from the advanced infection was almost unbearable, and the poor woman would not let anyone touch her, as the pain must have been excruciating.

She also had a little girl, no more than five years old, who wouldn’t leave her side. We explained to the husband – who had led us to her – that we were going to evacuate her with the girl. He protested strongly, but there was no alternative, as the little girl did not want to leave her mother’s side. Without proper medical attention the woman would have died a slow and painful death. He eventually accepted, after we promised him that both his wife and his daughter would be returned.

It was easier said than done, though. Firstly, we struggled to get her out of the narrow door of the hut once we had moved her onto a stretcher, and had to break down part of the wall. Secondly, it was nearly impossible to get her on top of the Buffel, as she screamed in pain at the slightest movement. The trip across the uneven terrain was pure agony for the wounded woman, and she wailed constantly as we bumped along.

Knowing that the helicopters would not enter the 20-km no-fly zone around Ongiva, we pressed on to find a suitable landing zone (LZ) before last light. In the meantime I pleaded with the OC to have the choppers dispatched, because I knew the evacuation of civilians was not a priority for the South African Air Force.

When the OC asked if we were out of the no-fly zone yet, I faked a grid reference and assured him that we were in a safe area. Finally we heard the Pumas and marked our position with yellow smoke.

“Kilo Sierra, this is Giant,” the lead pilot’s voice came on the air. “Is that your yellow smoke?”

“Giant, Kilo Sierra, that’s affirmative. I’m due northeast,” I said.

“You are still in the danger zone, man,” he responded. “You want me to come in?”

“That’s positive. The LZ is secured and safe. No problem,” I answered, and went on to describe the size of the LZ, wind direction and open quadrants.

Such was the nature and quality of our pilots that he didn’t query my decision or the safety of the area. He moved in swiftly and set the aircraft down, giving me a thumbs up through the canopy. They were flying off again in less than a minute. The last thing I saw before the doors closed was the wide-eyed little girl clinging to her mother’s dress, staring dumbfounded at the strange machine around her.

The story had a happy ending, as I learned some months later when I visited the Sector 10 operations room in Oshakati. The woman lost her leg, but was given a prosthesis to which she responded very well. The child was temporarily adopted by one of the nurses and was sent to school in Oshakati. Upon recovery, the mother was given a job at the sickbay – to assist and teach patients who had lost limbs and had to adapt to artificial ones. She was also allowed to go visit her family at Ongiva.

“To assume the responsibility of one’s decisions means that one is ready to die for them.”

– Carlos Castaneda,

Journey to Ixtlan

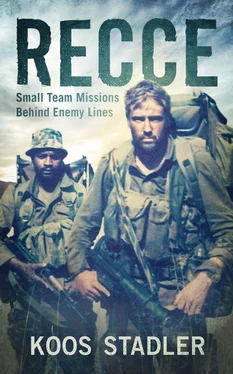

IT IS STRANGE how we are often connected to people even before we meet them. The regimental sergeant major (RSM) of 31 Battalion was a former member of the Reconnaissance Commandos and he often used to tell us about life in the Recces and about some of the characters he got to know there.

His firm favourite was a certain Diedies, whom he had allegedly recruited and who turned out to be a legend in the Special Forces. According to the RSM, André “Diedies” Diedericks and his buddy, a guy called Neves, operated only at a strategic level, conducting highly secretive and extremely sensitive operations far behind enemy lines.

I would listen intently as the RSM shared his experiences during his time with the Recces. Whenever he told us about Diedies and the small team reconnaissance group, I would pepper him with questions. The RSM often urged me to find a way to get in touch with Diedies, to do Recce Commando selection so I could join the Small Teams , but at the time I was too young and inexperienced to consider it seriously, and besides, I loved every moment with the Bushmen.

Little did I know then that this larger-than-life figure, who by the end of his operating career would be awarded two medals for bravery – the Honoris Crux Silver and the Honoris Crux Bronze – would become a comrade and close friend. To me, he was to become the personification of skill, dedication and sheer guts.

Those days at 31 Battalion were of the best any young soldier could hope for. We deployed on one operation after the other, steadily building up experience. Two weeks back at Omega would see us preparing for the next deployment. At Fort Vreeslik we invented new techniques, new pieces of equipment and fresh tricks to deceive our enemy.

The only way a bushwise guerrilla force like SWAPO could be matched in the African bush was for us to live as close to nature as they did – and to outwit them at their own game. I developed a firm belief – which I still hold today – that a guerrilla force in the dense bush of southern Angola and Zambia could not be beaten by firepower, at least not by firepower alone. After all, what would you direct your firepower at if your enemy was constantly on the move, or would “run away today to fight another day”, as we frequently encountered?

So we became masters in the application of tactics, in everything from silent movement to stalking, tracking and anti-tracking, patrol techniques and contact drills. We also became masters in reconnaissance, simply because that was what we did – day in and day out. When we were not on a deployment, we would stage exercises in the Caprivi and simulate different types of targets, or use the neighbouring bases to observe and infiltrate.

When I look back today, I can honestly say that there never was such a closely knit, dedicated and professional team as 31 Battalion recce wing. Obviously, I cannot compare the 31 Battalion recce teams with other professional outfits out there, such as the 32 Battalion “recces”, or even similar specialised groupings abroad, but, given that I spent the rest of my operating career in the Recces, I can compare them with the best reconnaissance teams in the South African Special Forces. I am immensely proud to have had the privilege of being part of such a unique band of brothers. It was an extremely valuable learning experience that laid the foundation for my career in the Recces.

At the end of 1981, my short-service contract expired and my military career got sidetracked for a while. By this time my father and two older brothers were all qualified ministers of the church, and were serving their respective communities. When my contract with the Defence Force expired, I had to make a decision about my future career. There was mounting pressure from my family to follow in the footsteps of my dad and two brothers, so I registered for a degree in Theology at Stellenbosch University and started my first year in 1982.

During my studies at Stellenbosch, I managed to slip away every holiday – to go back to Omega, the bush and my old comrades. Military call-ups provided valuable income, but more importantly offered a welcome break from the monotony of my studies. The first year, I managed to operate with Xivatcha every time I went back to 31 Battalion. In 1983, at the beginning of my second year at Stellenbosch, Xivatcha was suddenly not there when I arrived at the unit for the call-up.

Читать дальше