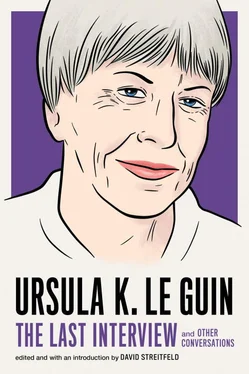

Урсула Ле Гуин - Ursula K. Le Guin - The Last Interview and Other Conversations

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Урсула Ле Гуин - Ursula K. Le Guin - The Last Interview and Other Conversations» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Город: London, Год выпуска: 2019, ISBN: 2019, Издательство: Melville House, Жанр: Биографии и Мемуары, Публицистика, sci_philology, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Ursula K. Le Guin: The Last Interview and Other Conversations

- Автор:

- Издательство:Melville House

- Жанр:

- Год:2019

- Город:London

- ISBN:978-1-61219-779-1

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Ursula K. Le Guin: The Last Interview and Other Conversations: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Ursula K. Le Guin: The Last Interview and Other Conversations»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Ursula K. Le Guin: The Last Interview and Other Conversations — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Ursula K. Le Guin: The Last Interview and Other Conversations», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

LE GUIN:Yes. Sort of a legend.

GILBERT:Was there much of that kind of legend-making, of make-believe, among you and your brothers in your childhood?

LE GUIN:Well—yes. All my brothers were nutty in different ways. We were all nutty. That brother is the only one who made up myths.

GILBERT:You didn’t do that?

LE GUIN:Well, not in public. He told his aloud.

GILBERT:I see. Have you always assumed that you would be a writer?

LE GUIN:Yes.

GILBERT:You didn’t decide one day, “That’s what I’m going to do?”

LE GUIN:No, I just knew it.

GILBERT:What led you to science fiction?

LE GUIN:Trying to get published. The stuff I wrote has always been—it’s had what you’d have to call a fantasy element.

GILBERT:It always did?

LE GUIN:Always, right from the start, except for the poetry. It took place in an imaginary country or something like that, and the publishers didn’t know what to call it; they didn’t know what it was. And they didn’t publish it. And I got back to reading science fiction in my late twenties, and I thought hey, you know, maybe I could call my stuff science fiction. So I sent a story to Cele Lalli at Fantastic magazine, and she bought it. And from then on I was a science fiction writer. They found a label for me. I had a pigeonhole. You have to have a pigeonhole. You have to start with a pigeonhole.

GILBERT:And you can’t be half in each of two pigeonholes, either!

LE GUIN:Well, you can once you get started, yes. I’m a juvenile writer, a science fiction writer, and now I’m—well, The Dispossessed and the Orsinian tales and so on are not labeled science fiction. Now I’m a writer. But you have to get started, apparently, in a box, with a label. Then you can break out of the box.

GILBERT:I know from speaking to other science fiction writers, like Joanna Russ, that sometimes you have frustrations if you’re starting out in your career, and you try two things at once. Or if you do something that doesn’t quite fit in one category or another. Then you didn’t call your science fiction “science fiction” yourself.

LE GUIN:No, it really is a publisher’s label, and a bookseller’s label. And it’s a useful label, I don’t resent it. I like to go to a bookstore and find the science fiction all together. And yet in a way it has—I don’t use the label much for my own stuff, partly because everybody uses it differently. It’s a convenience label, but it doesn’t really mean anything, and of course nobody’s ever been able to define it. “What is the difference between science fiction and fantasy?’ [ Laughs ]

GILBERT:Oh, yes. Of course, there’s the convenient label “speculative fiction.” “Spec fic.”

LE GUIN:“Spec fic.” Yes. [ Laughs ] It beats “sci-fic.” I don’t mind “s-f,” but “sci-fi,” for some reason, grates.

GILBERT:You take an obvious pleasure in dealing with myths, folk myths and magic; some of my favorite examples of that are from A Wizard of Earthsea, where one can follow the apprenticeship and the difficult and dangerous career of the mage Ged, and also in your story “The Word of Unbinding,” where the magician keeps trying to escape, and trying to change himself into various things. I think, by the way, that you have a good deal of sophisticated fun with stereotypes—folk expectations of a sort—in your story “Vaster Than Empires and More Slow.” I’ve noticed that in a great deal of your work—as in J.R.R. Tolkien, C. S. Lewis and some of the best writers of “fantasy” or “science fiction”—there are traces of myths and legends from all over this planet, and I noticed particularly the reluctance of certain of your characters to disclose their true names, or “truenames.” They show this reluctance much as the California Indian tribes do, I gather.

LE GUIN:Many peoples. Many peoples.

GILBERT:And when they don’t reveal their truenames, they don’t surrender their identities, or put themselves into someone else’s power. And I also noticed traces of cultures from other parts of the world—magicians, kings, the ability of magicians like Festin [in “The Word of Unbinding”] and Ged to transform themselves.

LE GUIN:Yes. Again, that’s very widespread, that kind of folk belief.

GILBERT:When you have an idea for a story, do all these ideas for myths in the work come to you at once? How do you sort this out?

LE GUIN:Well, there are several things involved here. One is that science fiction allows a fiction writer to make up cultures, to invent —not only a new world, but a new culture. Well, what is a culture besides buildings and pots and so on? Of course it’s ideas, and ways of thought, and legends. It’s all the things that go on inside the heads of the people. So, if you want to make a world and populate it, you also have to make up a civilization and a culture. My father preferred to go find these things; I prefer to invent them. I’m lazier than he was. Of course, where the myths and legends come from is from your own head, the whole thing’s coming out of your own head; but it’s a sort of combination process of using your intellect to make a coherent-looking body of culture that you can refer to. Tolkien, of course, is the master of this kind of invention. You get the sense in his books of an enormous history, a great body of legend and history and myth all mixed together, which he refers to, so that you get the sense that it really exists. Of course a lot of it does, the book he was working on when he died apparently contains a lot of this body of myths. Well, in a sense you have to make it appear as if it were real, but where it comes from is your own unconscious mind, and it’s your own myths—the ones you’ve absorbed and the ones we all—if Jung is right—have within us. We share them. And you’re drawing upon your own, your personal mythology.

GILBERT:And the fact that you remember or cherish certain myths from other cultures perhaps means that those are your own personal mythology.

LE GUIN:Anybody can hear a story, or read a myth, that hits something deep within them. The ones you remember are the ones that reflect something deep within yourself, which you probably can’t put into words, except maybe as a myth. If you’re a painter, you could paint it, if you’re a musician you could put it into music. But in words you have to do it indirectly. It has to come out as a story.

GILBERT:Have you always done this?

LE GUIN:Well, I got better at it as I went along. [ Laughs ] But yes, I guess so.

GILBERT:Was it hard to learn? It’s a complicated art form.

LE GUIN:Well, it just came natural to me. It’s obviously the line I always wanted to follow.

GILBERT:Have you ever felt that you had to resist a fascination with a particular culture, or felt that a particular culture was having too great an influence on your work?

LE GUIN:A particular, real, existing earth culture? No, no. Except one is culture-bound. One’s own culture is going to dominate one. Again, it seems rather immodest, but science fiction and anthropology do have a good deal in common. As the cultural anthropologist must resist and be conscious of his own cultural limitations, and bigotries, and prejudices—he can’t get rid of them, but he must be conscious of them—I think a science fiction writer has a responsibility to do the same thing if he’s inventing what he calls a different planet, a different race, alien beings, and so on. His beings can’t just be white Anglo-Saxon Protestants with tentacles. You do have to do some rethinking—and [with] a certain self-consciousness of your own bias. But you can’t get rid of your limitations; you can’t deculturate yourself.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Ursula K. Le Guin: The Last Interview and Other Conversations»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Ursula K. Le Guin: The Last Interview and Other Conversations» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Ursula K. Le Guin: The Last Interview and Other Conversations» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.